On September 8, Justice Kizito Magare temporarily

halted the operations of the panel of experts on protest victim compensation, pending

further directions on October 6.

Formed by President William Ruto in August this year, the panel was tasked with addressing state abuses against protesters since 2017. However, its placement under the executive office raised red flags about its independence.

Between 2023 and 2025, over 100 protest-related deaths have been recorded. Families of the missing continue to suffer in silence. Each number masks a personal tragedy of lives lost and denied justice.

Justice for protest victims cannot—and must never—be hinged on presidential goodwill. It is already rooted in law through Article 25, which guarantees absolute freedom from torture and cruel treatment. Article 28 safeguards dignity, while Article 23 and Article 50(9) empower courts to grant remedies and entitle victims to restitution.

Articles 2(5) and 2(6) of the constitution further integrate international law into the national legal framework, making treaties like the UN Basic Principles on the Right to Remedy, the ICCPR, the African Charter and the Convention Against Torture legally binding. In this light, reparations are not acts of favour but constitutional and international legal obligations owed to victims.

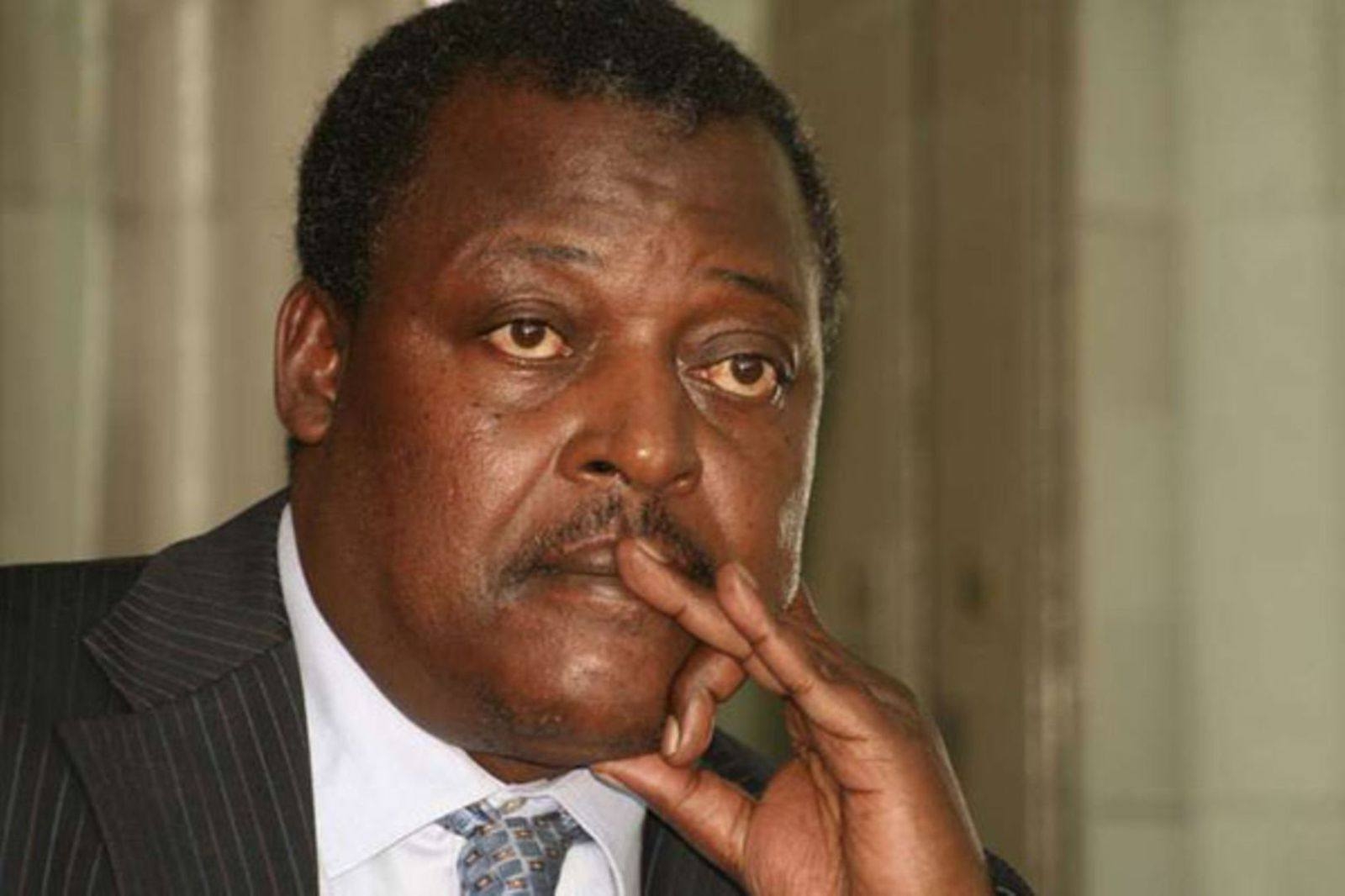

Our courts have gradually affirmed the right to redress for victims of state brutality. In 2010, the High Court awarded $500,000 (about Sh64 million at the current rate) to 21 former political detainees who were tortured in the 1980s under the regime of President Daniel Moi.

More recently, in March this year, the Court of Appeal awarded Sh15 million to six individuals who were unlawfully arrested and assaulted by police officers during protests against the excesses of Moi’s regime in 1992. And in April, 11 protestors received Sh200,000 each for rights violations during the 2024 demonstrations against Ruto’s regime.

These rulings show that compensation in Kenya is a constitutional obligation. At no point did Ruto intervene for these awards to be granted by the courts. The judiciary acted independently to execute its mandate. As such, the country cannot allow the treatment of such compensation as token of goodwill from the executive.

However, pursuing justice for protest victims is like fighting a wildfire with a garden hose. It is slow, costly and beyond the reach of most. Many urgently need medical care, burial support and financial assistance. But the court processes are slow compared to the urgency of relief.

Therefore, Kenya must entrench a comprehensive reparations framework, enacted by Parliament, transparently funded and overseen by an independent authority. This framework should guarantee swift compensation, safeguard the process from political influence and include all victims.

Most importantly, reparations must be linked to accountability. Without justice, compensation is merely hush money, a bandage on a wound that cries out for truth, fairness and meaningful reform.

Kenya needs not start from square one. South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission delivered financial and community reparations to apartheid victims, charting a course toward healing and unity. In Sierra Leone, a post-conflict reparations programme compensated survivors of violence and sexual abuse under credible national and international oversight.

These models prove that lawful, independent reparations work. Anchoring reparations in law would align Kenya with global human rights standards and give real force to the constitution’s promise of justice and dignity.

We cannot afford to settle for empty gestures. We must embrace lasting legal reforms. Anything less is a political bandage on a wound that demands healing, not hiding. The stakes are high, and history will remember the choice.

Program Manager for Inclusion and Political Justice at the Kenya Human Rights Commission