William Shakespeare warned that “corruption boil and bubble till it o’er-run the stew”.

And true to his words, graft in Kenya,

fuelled by ethnic patronage, elite greed, and frail institutions, has grown unchecked

beyond control owing to its pervasive nature.

The Corruption Perceptions Index by Transparency

International saw Kenya score 32 out of 100 in 2024, ranking 121st globally. For

more than a decade, the score has stagnated between 27 and 32, as graft in

Kenya deepens and widens.

Just three years after independence, the

1965 Ngei Maize Scandal exposed how public office could be manipulated for

private gain, sparking nationwide food shortages. Coffee smuggling and poaching scandals soon followed,

laying the foundation for a culture of impunity.

The Moi era entrenched graft as the price of

political loyalty. Land was dished out to allies, while scandals such as Goldenberg (Sh52 billion), Turkwell Gorge (Sh37 billion) and Anglo-leasing

(Sh9 billion) bled public coffers dry, but no convictions followed.

As a result, public services collapsed,

unemployment soared and IMF structural adjustment programmes deepened poverty. The

Kenya Anti-Corruption Authority that emerged did little more than mask unaccountability.

President Mwai Kibaki’s presidency raised

hopes of reform but was soon consumed by procurement scandals. The Anglo-Leasing

contracts resurfaced, and by 2010, Kenya was losing an estimated Sh270 billion

annually to corruption, almost 30 per cent of the national budget.

The Jubilee regime saw corruption perpetuated

unchecked. The National Youth Service scandal drained more than Sh9 billion,

while the scandalous Arror and Kimwarer dam projects swallowed Sh63 billion. Even

elections were not spared, as the “Chickengate” scandal revealed.

The Kenya Kwanza regime has not been left

behind. The 2023 Kemsa scandal cost taxpayers Sh3.7 billion. Toxic sugar

imports and shady tenders point to rot that runs much deeper than the headlines

suggest.

The 2024 National Ethics and Corruption

Survey reveals that the share of Kenyans asking for bribes rose sharply to 25.4 per cent in 2024 from 17.7 per cent in 2023. More than 52 per cent admitted to

paying bribes to access services, while 41.9 per cent admitted to receiving

them.

The Ministry of Interior is singled out as

the most corrupt institution, followed by Health and Treasury. While the

average bribe dropped to Sh4,878 in 2024 from Sh11,625 in 2023, this offers

little comfort.

The Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission

estimates that corruption drains Sh608 billion annually, nearly eight per cent of Kenya’s GDP. This is money that could build schools, equip hospitals, and

create jobs.

We expected arrests when President

William Ruto recently said that MPs pocketed Sh10 million each to sink anti-money

laundering laws. But what was offered was the creation of an unconstitutional multi-agency task force to “fight” graft, usurping the powers of other agencies, coined to

likely cover up the crimes or persecute political foes.

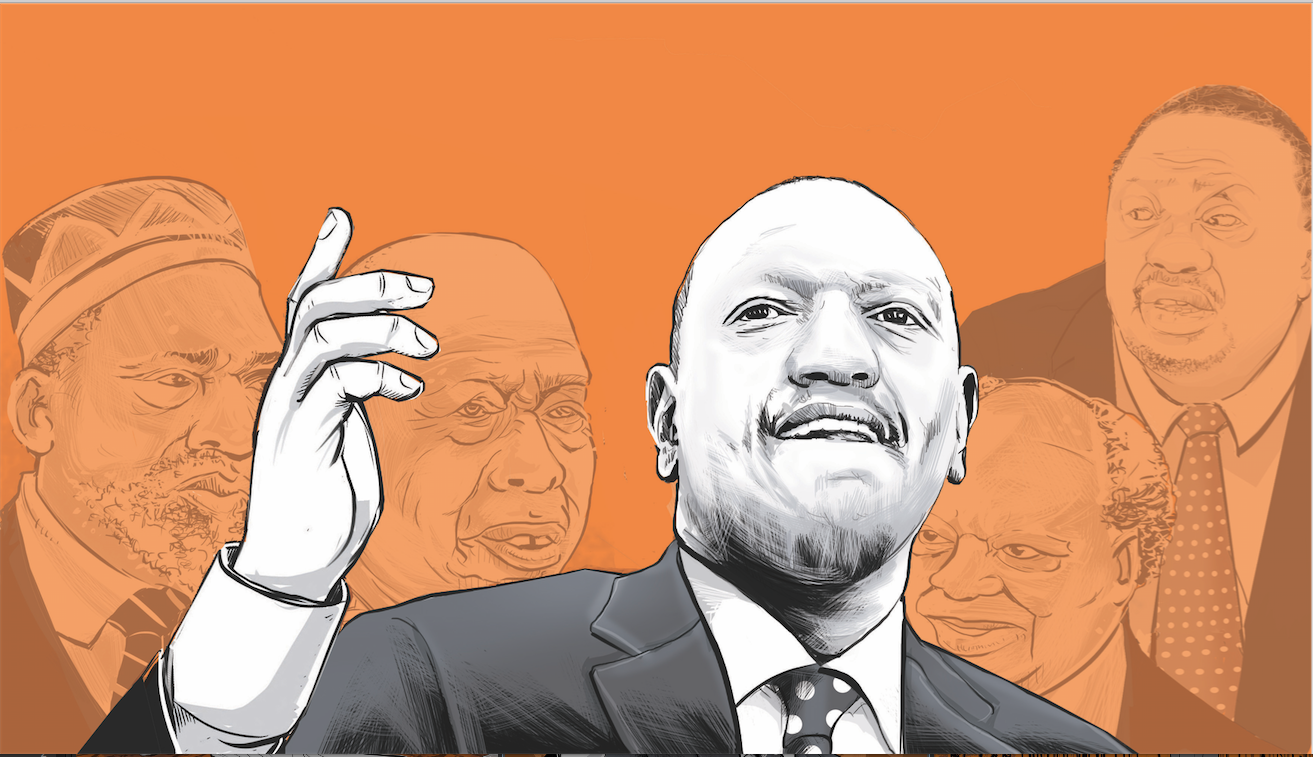

Across five administrations, one reality that

has remained unchanged is that corruption is deeply woven into the fabric of

politics. Over the years, it has morphed into a political resource, as it fuels

electoral campaigns, consolidates patronage networks, and silences dissent.

This entrenched system thrives because it

serves the interests of those in power, leaving citizens trapped in a cycle of

broken promises and eroded trust. To break this cycle, Kenya must draw lessons

from countries like Rwanda, Botswana and Estonia, where genuine political

will, independent institutions and stringent anti-corruption frameworks have

delivered tangible results.

Program Manager for Inclusion and Political Justice at the Kenya Human Rights Commission