In medicine, we are trained to search for causes. A fever has a source. A wound bleeds for a reason. But there are problems whose causes are not cellular or microbial. They are systemic—and harder to admit.

A new study published in The Lancet Global Health takes on such a problem: inefficiency in healthcare systems. Spanning 201 countries over nearly three decades, it asks a deceptively simple question: Are we getting the most health possible for the money we spend?

The answer is quietly devastating.

The researchers found that the average country could gain 3.3 years of healthy life expectancy per person if it simply closed the gap between its current performance and the best attainable at its spending level. For sub-Saharan Africa, that inefficiency gap stretches to 5.8 years. We are not just falling short—we are leaving years of life on the table. And we are doing so, not for lack of funds, but for how we use them.

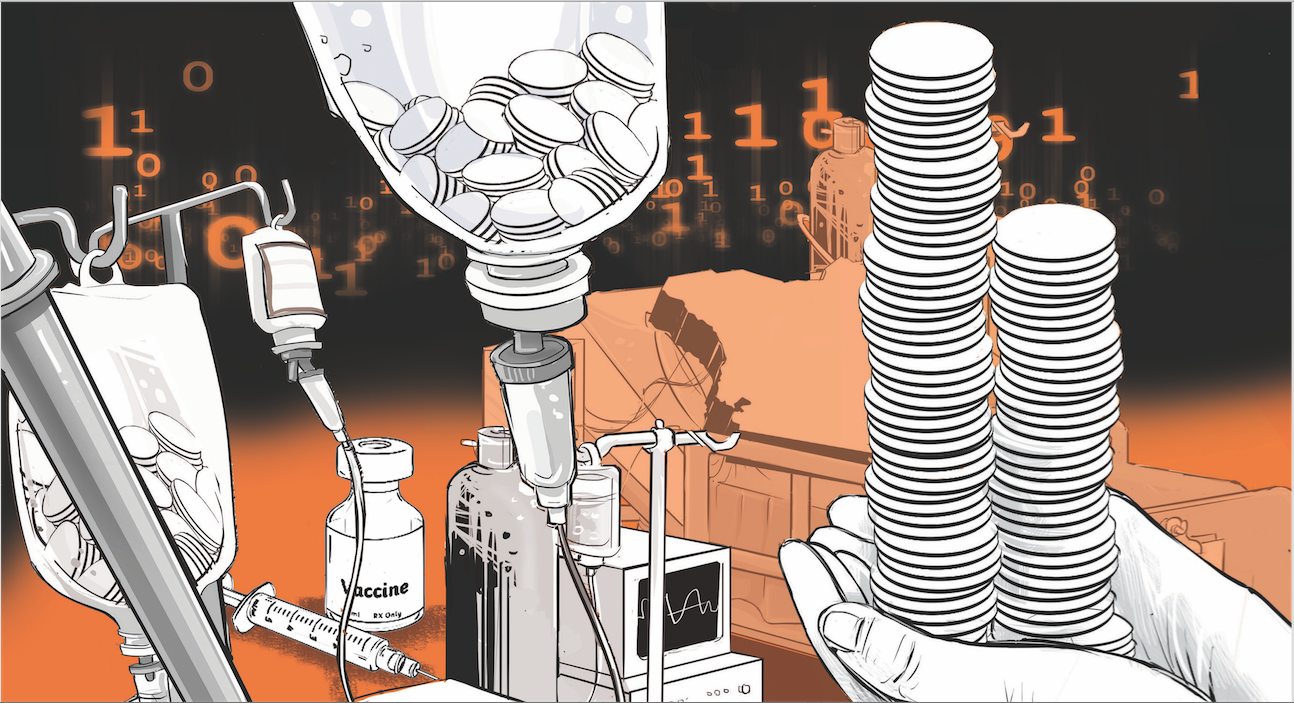

The study identifies several culprits, but one stands out: corruption.

In countries where governance is weak—where procurement processes are opaque and accountability elusive—health spending becomes detached from outcomes. Contracts are awarded not for value but for connections. Clinics exist on paper but not in service. Medicines go missing. And so do lives.

This is not just a moral failing. It is a measurable one. The data show a clear association between corruption and inefficiency in health spending. And the consequences are counted not just in dollars, but in years of health we fail to deliver.

We like to believe that aid, at worst, does no harm. But the study challenges that too.

In countries heavily dependent on fragmented donor assistance—with dozens of programmes, each focused on a narrow slice of health—the system becomes incoherent. Budgets are distorted, priorities multiply and administrators are left managing grants instead of guiding strategy. The study found that more fragmented aid often meant more inefficiency.

There is an alternative. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, consolidation of aid into a unified funding stream led to substantial savings and better coordination. It’s a reminder that how help is given matters as much as how much.

The findings also point to what works:

Preventive care—vaccinations, antenatal visits, skilled birth attendance—delivers exceptional value.

Infrastructure—roads, electricity, reliable staffing—is more than a development goal; it’s a health intervention.

Government-led financing, as opposed to out-of-pocket payments or external control, is consistently associated with better efficiency.

And perhaps most importantly, countries with stronger democratic institutions—where citizens can demand transparency and vote out failure—spend health dollars better.

What this study ultimately reveals is not just economic data. It is a map of choices.

Countries can choose to govern better. Donors can choose to coordinate more effectively. Leaders can choose to prioritise systems that prevent illness instead of reacting to it. These are not abstract decisions. They translate directly into longer, healthier lives for real people.

We often talk about scaling innovations in healthcare—new technologies, new treatments. But perhaps the greatest innovation we can pursue is one we already know how to do: spend well, govern honestly and plan together.

Inefficiency is not as visible as a failing ventilator or a crumbling hospital wing. It does not make headlines. But it is every bit as lethal.

It lives in the child who dies because a vaccine was delayed, in the mother who gives birth in the dark, in the nurse who spends more time chasing paperwork than caring for patients.

To address it, we will need more than funding. We will need intention. And integrity. Because the real question is not whether we can afford to do better. It’s whether we choose to.

Surgeon, writer and advocate of healthcare reform and leadership in Africa