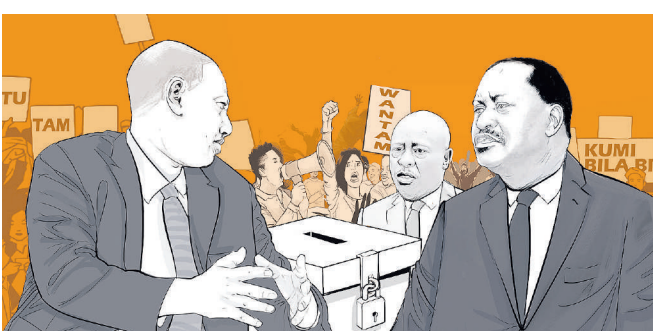

In Kenya’s evolving political arena, three

politically-inspired terms—wantam, tutam and haftam—have become markers of

political legitimacy and survival. Though informal, these acronyms refer to one-term,

two-term and half-term presidencies, respectively. They reflect deeper public

concerns about leadership, accountability and democratic performance.

This discourse is grounded in Article 142 (1) of the

Constitution of Kenya, 2010, which limits a president to two five-year terms.

But as the 2027 election approaches, these terms are increasingly shaping

political narratives, testing alliances and measuring betrayals.

Former Deputy President Rigathi Gachagua’s marginalisation

by 2024 vividly illustrates haftam—a tenure that legally seemed intact but was

soon politically eroded. His impeachment was a demonstration that wantam, tutam

and haftam are not just theoretical but are today’s political currency.

Wantam describes leadership that ends after one term,

either by choice or force. Gachagua has adopted this as a political weapon,

claiming betrayal by President William Ruto and warning that Mt Kenya’s

withdrawal of support will render Ruto a one-term president. His rallying call of

wantam

seems to resonate with his support base, predominantly Central Kenya.

Raila Odinga and Ruto have sharply condemned Gachagua’s

push for a wantam narrative, calling it undemocratic and harmful to governance.

They have dismissed Gachagua’s early 2027 campaigns, stressing that leadership

transitions should be left to voters, not personal vendettas. Raila has accused

Gachagua of putting bitterness before national unity.

Wantam has also found support among Gen Z protesters, who

use it as a form of real-time democratic accountability and mobilisation. For

them, it is not about betrayal or loyalty; it is about delivery and justice.

Tutam refers to a president completing two terms if

re-elected. Legally, this is the default. Politically, it is no longer

automatic. Ruto and his allies insist he deserves a second term to fulfil his

Bottom Up Economic Transformation Agenda. However, the youth are demanding

visible progress, not deferred promises.

For younger Kenyans, tutam represents renewed trust. They

see the presidency as a contract, not a coronation. If performance falls short,

the contract is revoked—at the ballot box, not the courtroom.

Raila, while upholding electoral accountability, has also rejected

Gachagua’s sustained tribal and transactional approach to politics. He denounced

the “shareholding” logic used to distribute state benefits based on political

loyalty.

Declaring “all Kenyans pay taxes” ,he rejected Gachagua’s

overtures of anti-Ruto alliance, including support from Mt Kenya for a 2027 bid.

Raila’s stance affirms politics of inclusion over ethnic patronage.

Once unthinkable, haftam now reflects the reality of

political demotion despite constitutional protection. Gachagua’s tenure is a

textbook case—stripped of influence and his role as Deputy President.

Haftam is not limited to the deputy presidency. At the

presidential level, Gen Z-led civic uprisings in 2024–2025 have shown that mass

dissent can pressure even constitutionally secure leaders into political limbo.

While Article 145 outlines the path for impeachment, public disapproval can

render a leader ineffective without formal removal. Haftam, then, is a people’s

verdict. It reflects a refusal to be spectators in a democracy they help shape.

Kenya’s youth, particularly Gen Z, are no longer passive

participants. Once dismissed as “digital dreamers”, they have emerged as

powerful political actors. They do not rely on political parties to channel

their dissent. They protest visibly, organise digitally, mobilise physically and

speak directly to power.

To them, wantam is a warning, tutam is a scoreboard and haftam

is a hard reset. The old model—first term for politics, second for delivery and

legacy at the end is gone. Now, the first term is the legacy, judged instantly

and relentlessly.

These new metrics are reshaping politics. Term limits still

exist, but they now intersect with performance standards. Time in office is no

longer assumed; it must be justified. For Kenya’s leaders, the message is

stark: constitutional legitimacy and coalition math are no longer enough. Survival

demands delivery, trust and transparency.

Time in office is not a gift. It is a test. And Kenyans, especially

the youth, are the examiners.

Political advisor and expert in leadership

and governance