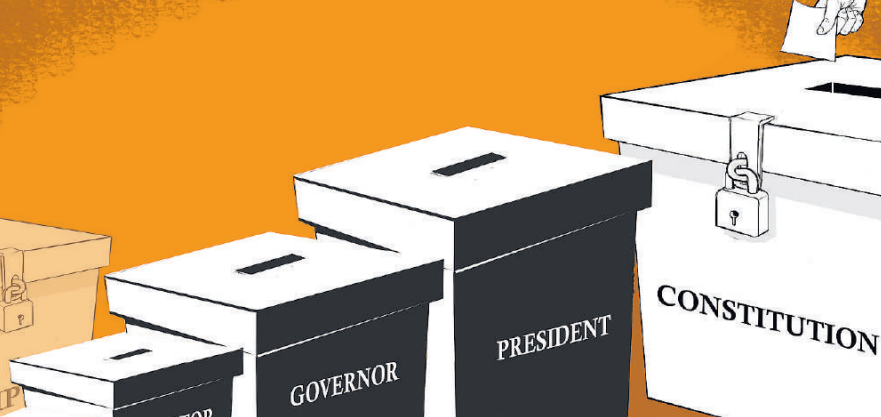

In August 2027, Kenyans will undertake their civic duty by electing their president, MPs, governors, senators, MCAs and women representatives. These six ballots have defined our electoral architecture since 2013. However, the upcoming general election presents a critical constitutional imperative—there must be a seventh ballot. This additional vote must not concern a candidate but a question—a referendum on the future structure and character of the Republic of Kenya.

The

Constitution of Kenya (Amendment) Bill, 2023, now before Parliament, is not an

ordinary statute. It is the legislative offspring of the National Dialogue Committee

report, which itself emerged from a consensual political process aimed at

resolving long-standing governance and electoral issues. The committee was

tasked with facilitating dialogue, fostering consensus and recommending appropriate

constitutional, legal and policy reforms on issues of national concern. While

the dialogue was a commendable step toward political stability and

institutional harmony, the Bill it generated proposes sweeping constitutional

changes that, by their scope and substance, cannot be enacted without a direct

mandate from the people.

This Bill touches multiple foundational aspects of the constitution: the architecture of the Executive, the jurisdiction and structure of the Judiciary, the tenure and functioning of Parliament, the autonomy of political parties, the regulation of public funds and the institutionalisation of oversight mechanisms. Specifically, it proposes the creation of the Office of the Prime Minister, formally recognising the Leader of the Opposition and two deputy leaders and extending the Senate’s term from five to seven years.

These are not peripheral amendments. They constitute structural re-engineering of the republic. Under the doctrine of the basic structure—now firmly entrenched in Kenyan jurisprudence following the BBI rulings—such alterations must not only satisfy procedural thresholds under Articles 256 and 257 of the Constitution but must also respect the principle of popular sovereignty. The people, as the ultimate custodians of the constitution, must have their say.

The Supreme Court, Court of Appeal and High Court have already pronounced on this matter. In the BBI litigation, the courts held that certain amendments—particularly those that alter the constitution’s basic structure—must be subjected to a primary constituent process, which includes civic education, public participation and a referendum. The courts were unequivocal: Parliament alone cannot usurp the people’s sovereign role in remaking the constitutional order.

Some proponents of the current Bill argue that because it proceeds by parliamentary initiative, it need not be submitted to the people. That reasoning is flawed, both legally and morally. The threshold is not merely procedural—it is substantive. The question is not how the amendment is initiated, but what it seeks to do. When a Bill seeks to alter the composition and functions of the Executive, restructure the Judiciary and reassign powers and protections under the constitution, then it goes beyond legislative competence. It enters the realm of constituent power.

Furthermore, the Bill includes a controversial provision whereby elected leaders automatically lose their seats upon resignation or deregistration from their political party. This move, though justified as promoting party discipline, could dangerously curtail electoral sovereignty. It removes the discretion of the electorate to retain a representative who defects for legitimate reasons, and instead places disproportionate power in the hands of political party bureaucracies.

In addition, the constitutional entrenchment of the National Government Constituency Development Fund, Senate Oversight Fund, and Affirmative Action Fund raises critical questions of fiscal federalism. While these funds serve crucial functions, embedding them in the constitution forecloses future reform and ties the hands of subsequent administrations and Parliaments. It may also compound fiscal pressures at a time when the country is facing growing debt obligations and a constrained public expenditure framework.

Therefore, the question we must ask is not whether the Bill is well-intentioned, but whether it is legitimate without the people’s endorsement. The answer lies in the constitution itself. Article 1(1) affirms that all sovereign power belongs to the people. That sovereignty is not abstract. It is exercised through periodic elections—and, where necessary, through referenda.

The 2027 election offers a vital constitutional moment—an opportunity to restore the legitimacy of the reform process. Introducing a seventh ballot would empower Kenyans to directly approve or reject the proposed amendments, ensuring that constitutional change aligns with both democratic values and legal principles. This is not a rejection of reform, but a reaffirmation that such reform must be people-driven, transparent and constitutionally sound.

Let 2027 be more than a political contest. Let it be a reaffirmation of the people’s sovereignty. Let Kenyans cast six votes for their representatives—and a seventh for their republic. Let the people decide.