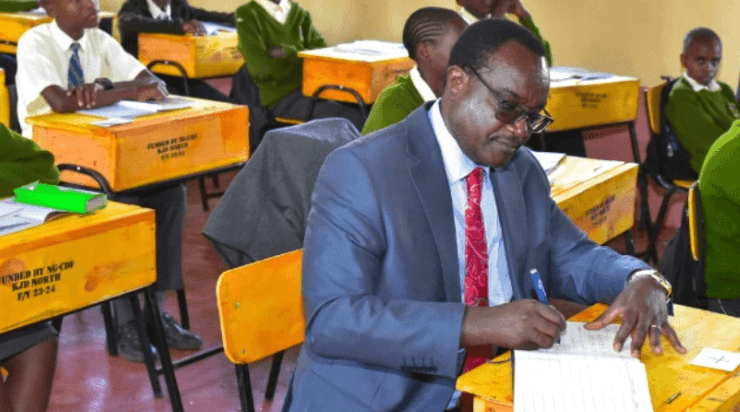

Linet Wanjala, an agronomist with Safi Organics

Fertiliser explains soil testing at a farmer's Field Day in Waruhiu Agricultural Training Centre (ATC) in Githunguri, Kiambu county /AGATHA NGOTHO

Linet Wanjala, an agronomist with Safi Organics

Fertiliser explains soil testing at a farmer's Field Day in Waruhiu Agricultural Training Centre (ATC) in Githunguri, Kiambu county /AGATHA NGOTHOPeter Muriithi, a long-time vegetable farmer from Githunguri, admits he has never carried out soil testing on his farm. But after attending a training session at the Waruhiu Agricultural Training Centre, that will change.

Muriithi, who has farmed for more than two decades, said the demonstrations opened his eyes to how simple and immediate the process can be.

“I’ve learnt that soil testing can be done in real time and you get the results immediately,” he said.

“I always thought it was a long, complicated process, but now I know better.”

According to the Soil Atlas Kenya Edition 2025, published by the Heinrich Böll Foundation, 63 per cent of Kenya’s soils are acidic, 80 per cent are deficient in phosphorus and 75 per cent have depleted organic carbon.

The report explains that soil degradation is a global silent crisis due to unsustainable agricultural practices, deforestation, pollution and climate change.

Its effects may not be as immediately visible as deforestation or ocean pollution, but its consequences are profound and far-reaching.

“One-third of the world’s soils are degraded, with significant impacts across Africa, Europe and beyond. In Kenya, soil degradation is worsened by land overuse, deforestation and climate variability, threatening agricultural productivity and rural livelihoods,” the report states.

“While these challenges are deeply felt locally, they are part of a broader global issue that affects food security, deepens social inequalities and complicates efforts to address climate change.”

The report highlights that the overuse of artificial inputs like nitrogen and phosphorus not only weaken soil resilience, but also accelerate climate change through greenhouse gas emissions. Additionally, soil erosion and desertification continue to threaten fertile lands, disrupt livelihoods and drive migration.

Muriithi now understands that soil testing is no longer optional.

“I’ve realised the soil speaks. It tells you what it needs. Now I know I must listen,” he said, holding a brochure detailing where he could get his first test done.

Early this year, Agriculture PS Paul Ronoh rolled out a nationwide Digital Soil Testing programme targeting more than 40 counties.

The ministry, in partnership with the Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organisation and the World Bank Group, Agra and CIFOR-ICRAF (supporting innovation), deployed youth agri-preneurs per ward with handheld tools to map soil health, combat nutrient depletion and guide farmers on precise fertiliser use via digital maps for better yields.

The move is aimed at providing rapid analysis and a push for data-driven farming to boost food security.

Muriithi was among dozens of farmers who took part in a field day at Waruhiu ATC in Kiambu county, held in line with this year’s World Soil Day, marked globally on December 5. The training aimed to equip farmers with practical knowledge on soil health and the importance of testing before planting.

Mary Irungu from Pelum Kenya said the training focused on strengthening soil health through better testing, regenerative practices and responsible use of inputs. She noted that many Kenyan soils continue to degrade due to years of poor practices.

Agronomists led practical demonstrations on how regular soil analysis helps farmers understand nutrient deficiencies, choose the right fertilisers and cut losses caused by guesswork. They also showcased sustainable land-management techniques, including composting, crop rotation and the use of organic matter to replenish tired soils.

Irungu stressed that soil is the foundation of food and health.

“We are raising awareness on why we must take care of our soils, because the nutrients missing in the soil will also be missing in our food,” she said.

Many Kenyan soils have become highly acidic, largely due to overuse and misuse of synthetic fertilisers and Irungu urged farmers to begin with soil testing so they can “heal their soils with the right medicine”.

This year’s theme for World Soil Day—‘Healthy Soils for Healthy Cities’—linked soil health to the wellbeing of growing urban populations.

Irungu said Kiambu was targeted because of its rapid urbanisation, rising real estate developments and shrinking arable land.

“If we promote agroecological practices such as agroforestry and make good use of urban waste by converting it into organic fertiliser, we can support both urban and rural farmers and strengthen food security in our cities,” she added.

Soil sealing, which is caused by construction that leaves land covered by concrete, was also flagged as a growing concern in urbanising counties like Kiambu.

Irungu noted that healthy soils are important not only for food production, but also for preventing floods and supporting biodiversity.

Linet Wanjala, an agronomist with Safi Organics Fertiliser, took farmers through the importance of carbon in the soil. Safi Organics produces NPK-rich organic foliar feeds containing macro and micronutrients vital for strengthening crops, including calcium, boron, magnesium and phosphorus.

Wanjala explained that their organic fertiliser, made from rice husks, returns carbon to the ground and helps neutralise soil acidity.

“We also have organic lime that reduces acidity and locks carbon into the soil, allowing farmers to harvest higher-quality produce,” she said.

“What you feed the soil is what you get. Soil is the heart of production and without healthy soil, there is no farming.”

She noted the need for farmers to conduct soil tests every one or two years and more frequently for those who do not practise crop rotation. Their tests, she said, cover both nutritional deficiencies and soil-borne diseases.

“If the soil has low magnesium, we recommend the right organic input to restore it. And if we find disease, we work with the farmer to protect the crop early enough to avoid losses.”