Last Wednesday, as Kenya woke up to the discovery of nearly Sh700 billion gold, and Donald Trump signed off the longest shutdown in US history, a quiet tragedy was unfolding in the Mediterranean Sea.

‘42 migrants presumed dead after boat sinks off Libya's coast, UN says’ was its unassuming heading. Only seven people survived the daredevil trip from Africa to Europe, and they were shipwrecked for six days before rescuers arrived, reported the UN’s International Organisation for Migration.

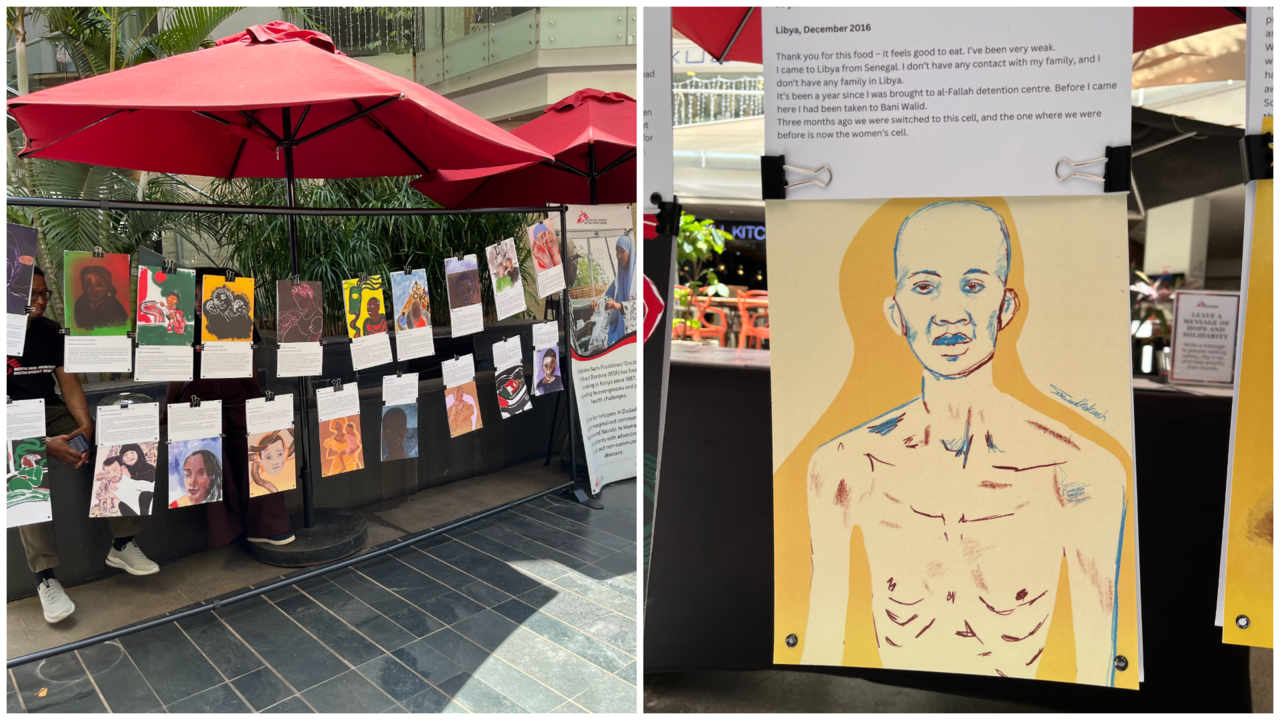

The weight of the story would have escaped me if I had not just attended an exhibition of survivors’ stories in Nairobi the prior weekend courtesy of Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders), freshly booted out of Libya where they’d been offering humanitarian aid since 2015.

Titled ‘Humans in Transit’, the gallery was set up outdoors in Village Market, a melting pot of expats and tourists. Portraits of 400 survivors, unnamed to protect their identities, were pegged onto lines, with briefs of their ordeals written beneath the illustrations. Most were from West Africa but some came from East Africa and as far as the Middle East. Many were speaking from detention camps in Libya or aboard search and rescue vessels.

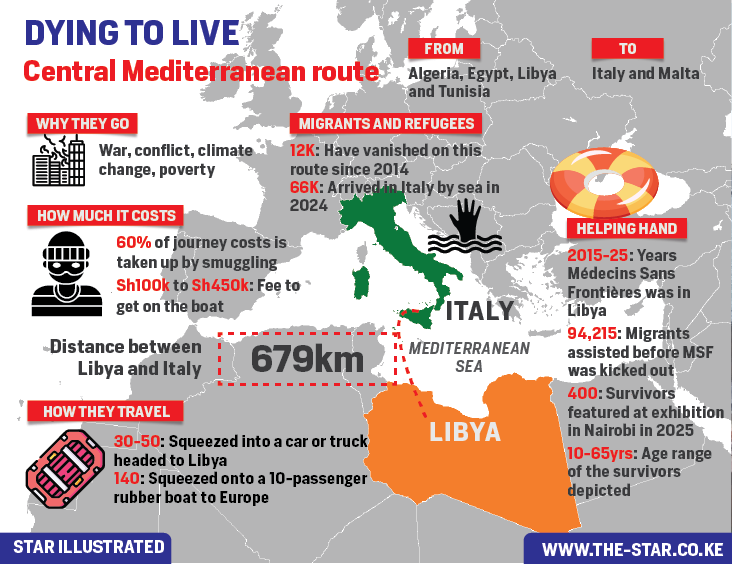

They went through the so-called Central Mediterranean route (from Algeria, Egypt, Libya and Tunisia to Italy and Malta), the most frequented pathway, but not the only one. Others take the Western Mediterranean route, from Algeria and Morocco to Spain.

“Which is the most touching story?” I asked a staff member from MSF when I arrived.

“I couldn’t even finish reading some of them,” she said.

Even the illustrators, themselves migrants, experienced an emotional roller coaster.

“As I drew,” said Barly Tshibanda from DR Congo in a written testimony, “I remembered not only my journey as a refugee who took the same road as those I am illustrating, but also the invisible graveyard that the Mediterranean has become… I felt both connected and furious.”

The other illustrators were Souad Kokash from Syria, Ngadi Smart from Sierra Leone and Tawab Safi from Afghanistan. Each contributed 100 illustrations.

Throuh the work of their hands, I immersed myself in the world of the migrants and refugees. Emerging three hours later with a heavy heart and a vicarious trauma.

TRAVELLING TO LIBYA

The picture painted in my mind was, in one word, desperation. People as young as 10 years old, ranging to 65, were finding their way to Libya for that one shot at a better life.

One would be smuggled there sometimes by choice, sometimes kidnapped at the country of origin or even in Libya for onward trafficking. Often times, you would be lured on false promises of work in Europe only to end up in detention, with your family forced to pay a ransom for your release.

Poor folks don’t just up and leave. They save painstakingly for months or borrow from friends and relatives.

You either pay the smugglers up front or in instalments. Transport costs vary depending on the country of origin, but the Mixed Migration Centre notes that smuggling takes up 60 per cent of journey costs.

You are packed like potatoes into a truck or a car; one survivor was among 30 people squeezed into a Toyota. Then you endure a gruelling trip across the Sahara. Some die along the way, you see crosses in the desert where they were hastily buried.

If you make it to Libya, it is no cosy stopover. It was notorious for illegal migration even under Muammar Gaddafi, when about 20,000 people transited through it in a year, but his fall after Nato’s military intervention during the 2011 Arab Spring opened the floodgates.

Outflows peaked at 180,000 in 2016 before tougher border control under the EU’s behest brought it down to 66,000 last year. But the more governments fight it, the more dangerous routes migrants take, and the more fees smugglers charge.

You could be caught by authorities before you get to Libya or upon arrival. While in other countries you would be taken to court, sentenced to a few months in jail for being in the country illegally and repatriated, in Libya, you are taken to a detention centre. A country split in two by civil war and riddled with militias, the law of the jungle prevails.

In prison, you are beaten even when eating or going to the toilet, usually by the black guards of the Arabs. At night, men are taken out and raped, too.

Even if you escape arrest, when you arrive, your phone is the first thing to be taken; “In Libya, a black person can’t carry a phone,” one survivor said. This cuts you off from the world of relatives and friends, leaving you stranded. You may not have told them you were going, hoping to break the awkward news from a better position after arriving in Europe, but now, you are in darkness.

Your passport is also seized, ensuring you can’t leave the country even if you escaped. Then you are taken to a cell tucked away in the basement of a villa with a garden that you wouldn't suspect is a front for human trafficking.

There, you are detained for months in horrendous conditions, with little food and dirty or no water, forcing you to drink your own urine. Men have to work to be fed. Women are sold as prostitutes. Arabs come to pick them at random, and some never return.

CROSSING THE SEA

After months in limbo, your turn to get on a boat finally reaches. All remaining valuables are taken from you first, including clothes and shoes. Libyan smugglers charge $750 to $3,500 (about Sh100,000 to Sh450,000) for a place on the boat.

Still alive? Don’t count your chickens. Just when you think the worst is behind you, your date with Mother Nature arrives.

On a rubber boat meant for 10 people, you are squeezed amongst about 140 people instead. Imagine 100-plus people in a 14-seater matatu? It’s that bad. To make matters worse, you will navigate 367 nautical miles (679km) on tempestuous waters like this.

You eat pasta cooked in sea water, and only have sea water to drink. Fresh water has to be paid for. No life vest is provided. Fall overboard without any swimming skills or land nearby, and your fate is sealed.

If the boat is spotted by the coast guard, they shoot at you or throw something to break the motor. Then they take you to a detention centre in Tripoli. There, you are beaten and half-starved until your friends or family pay 1,000 to 3,000 Libyan dinars (Sh23,000 to Sh71,000) for your release.

It takes three days to cross from Libya to Italy. Chances are the boat will capsize barely off the coast of Libya, with survivors drifting at sea for up to 10 days before they are rescued, if at all.

That's where organisations like Médecins Sans Frontières come in. MSF feeds, treats and offloads migrants and refugees at a safe place to disembark, usually Italy or Malta. It considers Libya unsafe for them, and coast guards are unlikely to welcome the lot back anyway.

One of the most iconic illustrations depicted a Senegalese migrant with a skeletal torso, saved from the jaws of death. His first words to the rescuers: “Thank you for this food. It feels good to eat. I’ve been very weak.”

NOT AFRAID TO DIE

The story does not end there. Even after being rescued, many people still come back to Libya to try their luck again. And again. And yet again. Until they die or make it to the other side alive.

Imagine the horror some face after going through all this to make it to Europe only to be deported. Asylum is in short supply.

Not forgetting that many never get the chance to argue their case. They are swallowed by the sea en route. Since 2014, 12,000 people have vanished at sea on the Central Mediterranean route, according to the Missing Migrants Project.

And the number could be higher since this is only what has been documented. No one really knows how many smuggler boats leave Libya, Tunisia and Morocco and sink before they reach their destination or call for help. Many are unreported, “invisible”, vanished without a trace…

MSF engagement officer Abdi Mohamed took me out of my reverie to emphasise that the cold, hard truth. “These are real stories of people who have been rescued by MSF from Libya,” he said.

Afghan illustrator Tawab Safi drove the point home. “With every line and every face I drew, I wanted to convey humanity because refugees are often dehumanised and reduced to numbers,” his testimony noted, echoing the sentiments of his colleagues.

CRY FOR AWARENESS

The exhibition was a cry for awareness after MSF was kicked out of Libya. Nairobi was the third city to host it after Berlin in Germany and Ferrara in Italy. In his opening speech, MSF communications director Sam Taylor hailed Nairobi as a dynamic hub connecting people from all walks of life.

“In every neighbourhood, in every market, you can hear stories of where people have come from and where they hope to go,” he said.

The exhibition ran from October 31 to November 9, concluding on the same day MSF was given as a deadline by the Foreign Affairs ministry to leave Libya. Steve Purbrick, head of programmes for MSF in Libya, said no reason was given for their expulsion.

“In a context of increasing obstruction of NGO intervention, drastic cuts in international aid funding and the reinforcement of European border policies in collaboration with the Libyan authorities, there are now no international NGOs providing medical care to refugees and migrants in western Libya,” he said in a statement.

Kenya, which has two of the world’s largest refugee camps (Kakuma and Dadaab), is feeling the pinch. The UN's World Food Programme head of refugee operations in Kenya Felix Okech said in June the agency had been forced to slash food rations. “If we have a protracted situation where this is what we can manage, then basically we have a slowly starving population," he said.

While I didn’t see any account of a Kenyan in the Libya escapades, Kenya has been flagged as a major source and transit point of human trafficking. Just last month, the Daily Nation reported the case of Khalid Mohamed, a Somali national smuggled from Kenya then locked up in Libyan cells operated by human smugglers.

Considering the growing crackdowns on illegal immigration worldwide, nowhere more starkly than in Trump’s America, I reckoned governments were seeing the humanitarian organisations helping them as enablers.

As I left the exhibition, another MSF employee gave me a sticker with drawings of refugees, some fleeing, some riding a rubber boat and some climbing a wall. All around the words: ‘Seeking safety is not a crime’.

Tom Jalio is the features editor of the Star and producer of the ‘Jalio Tales’ YouTube channel