Diagnosed with bipolar disorder at 21, he has spent nearly two decades navigating a life punctuated by extremes, from euphoric highs that lift him to unimagined heights, to crushing lows that leave him incapacitated.

His story is one of endurance, resilience and the quiet battle of millions living with mental illness in Kenya.

“I have lived with bipolar for over 20 years,” Boiyo begins, his voice steady but laced with exhaustion.

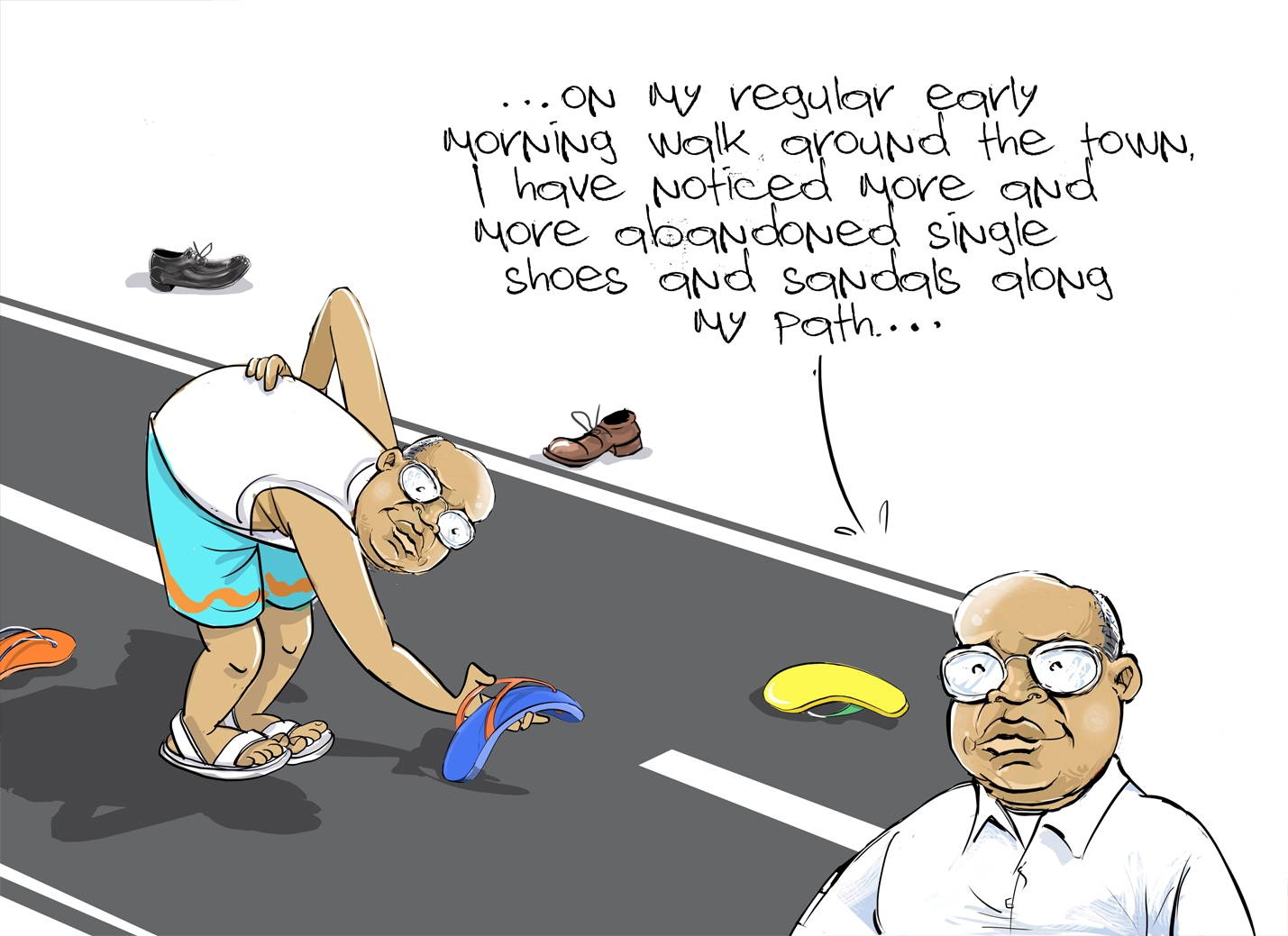

“It began with a manic episode during my final year in college. When the episode was over, I had ‘donated’ my possessions. I was left confused and depressed.”

The condition has been very tough on him and his family, and very costly.

“Every coin I earned went into medication. Sometimes I could not even develop myself financially because the medicine is expensive.”

His journey is echoed by many Kenyans living with the condition, including 24-year-old Patience Kyalo, who was diagnosed with bipolar disorder in 2024.

Together, their stories paint a vivid picture of what it means to live between highs and lows, to fight stigma and to seek dignity in a society still grappling with the realities of mental health.

WEIGHT OF DIAGNOSIS

For Samuel Boiyo, the first challenge was understanding the illness itself. In the early 2000s, mental health was widely misunderstood in Kenya.

Depression and mania were often explained away as curses, witchcraft or spiritual possession.

“In my village, people didn’t know about intervention,” he recalls.

“Even when I was sent to prison, they said I could have stolen someone’s possessions and they did some juju to me. Or that I had been bewitched.”

Samuel was arrested a few months after arriving in Nairobi, where he ran his jewellery business.

It was during what would have been a normal day at the CBD when he got an attack. He went to sit down, having confused another trader’s stall with his, when he was accused of intention to steal.

The public landed on him, despite pleas, only to be rescued by police, who took him to Industrial Area, Nairobi Remand.

“In prison, they said I must have been bewitched. Even some officers mocked me, saying I was pretending. At times they beat me for the fun of it,” he says.

“But the truth is, without medication, my brain was not stable. I was a danger to myself, not to others.”

Confusion, stigma and fear defined those early years. Relatives whispered. Neighbours avoided him.

“Mental illness isolates you, even from your own family,” he says solemnly.

In moments of mania, when his energy surged, he was dismissed as “possessed”.

During depressive episodes, when he would lock himself away for weeks, people assumed he was lazy or bewitched.

“It took education and persistence before I realised bipolar disorder is a medical condition,” he says.

“Finally, I came to see it as a medical case. I had to take my medication and listen to the doctors at Mathari Teaching and Training Referral Hospital. That education helped me start improving.”

For Patience Kyalo, the journey to diagnosis came two decades later but with similar confusion.

In 2023, she began experiencing dramatic mood swings. Some days, she would feel invincible, staying up all night studying and planning projects. Other times, she could not get out of bed.

“At first I thought I was just stressed,” she recalls. “But then the patterns became too obvious. My family noticed I was either too high or too low. There was no in-between.”

It was only after she sought psychiatric help in Nairobi that she received a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

“Hearing the doctor say it was bipolar felt like a relief but also a weight. Mostly though, it was like being handed a death sentence,” she says.

“Finally, there was an explanation. But I also knew it was not something that would just go away.”

COST OF SURVIVAL

Both Samuel and Patience quickly discovered that managing bipolar disorder comes with financial strain.

“The first-generation drugs were cheap but had so many side effects. I was always drowsy and weak,” Samuel says.

“The newer ones are better, but they cost me more.”

Samuel spends nearly Sh10,000 a month on medication alone.

“Treating mental illness is not like malaria or something simple,” he says. “You borrow, you are given, and many people miss medication because of cost. It is a lot.”

He explains that missing medication is not an option due to the risk of relapse.

For Patience, the financial challenge is compounded by therapy sessions.

“I take mood stabilisers, and I also go for psychotherapy.

Each session costs about Sh3,000, and you need it regularly. Sometimes I skip sessions because I just don’t have the money.”

Both highlight the gaps in Kenya’s health system. While the National Health Insurance Fund previously supported some medication, recent policy shifts have left patients struggling.

“The government needs to create value for mental health, give medication at a good price and follow up with patients regularly,” Samuel urges.

Bipolar disorder is often described as a pendulum between two extremes: mania and depression.

For Samuel, these swings once dictated every aspect of his life.

On some days, he opens his shop only to find himself giving away goods to strangers by evening.

“During mania, I feel overly generous, invincible,” he says. “But the consequences come later.”

Depression, on the other hand, leaves him paralysed.

“There are times I cannot even step out of the house,” he admits. “Even basic things like bathing, brushing my teeth or eating feel impossible.”

Relationships bore the brunt. For years, he avoided visiting neighbours or relatives out of fear his erratic behaviour might harm them.

His marriage nearly collapsed.

“At some point, my marriage got so close to an end. My wife left with the kids because she could not handle the highs and lows. I don’t blame her,” he says.

“It was until my therapist encouraged me to attend sessions with her that things stated getting better. We have been stable for the last decade. Today, she even helps me monitor my medication.”

Patience shares a similar battle. “When I am high, I take on too much,” she says. “I start projects I can’t finish, I talk too much, I spend recklessly. But when I crash, I feel like the world has ended. I can’t answer calls. I can’t face people.”

Her friendships have suffered. “Some people think I am unreliable. They don’t understand it’s the illness. I’ve lost friends but I’ve also gained a few who are patient and supportive.”

Samuel and Patience credit therapy for helping them regain balance.

“Before psychotherapy, I could not come out of the house or face people. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy gave me the tools to stop destructive thoughts,” Samuel recalls.

“Now, it balances me. It gives me insight into life. I accept myself, my illness and I live positively with it.”

Patience describes therapy as a safe space.

“My therapist helps me recognise my triggers,” she says.

“For example, I now know lack of sleep can push me into mania. I keep a sleep schedule and I write a mood journal. These small things keep me grounded.”

TREATMENT

Dr Evans Oloo, a psychologist, says bipolar disorder is a mental condition that affects mood regulation.

An individual experiences rapid shifts, from sadness to euphoric highs.

He says people tend to think bipolar disorder is just about mood swings, but it is more complex.

“A manic episode can push someone into risky behaviour, including overspending, unsafe sex or even giving away properties,” Oloo says.

“A depressive episode can leave someone in bed for weeks. Families often interpret this as laziness or stubbornness, when in reality it is a medical crisis.”

He advocates both medication and therapy, adding that medication stabilises the neurochemical imbalances in the brain, allowing individuals to function.

Therapy, on the other hand, provides coping mechanisms to handle stigma, family dynamics and social pressures.

“Therapy is not about curing bipolar; it is about giving patients’ tools,” Oloo says.

“For example, teaching them to identify triggers, develop daily routines and build support systems. Without therapy, even with medication, relapse is very common.”

Dr Nelly Kamwale, a consultant psychiatrist, says there are different types of bipolar disorder.

“There is bipolar 1, bipolar 2 and cyclothymia, each with varying severity,” she says.

Kamwale says bipolar disorder arises from a combination of genetic and neurochemical factors.

“If a parent has bipolar, the child has a higher risk,” she says.

“But environmental stress like trauma, poverty or substance abuse can trigger onset. That is why many people experience their first episode in early adulthood.”

She says treatment involves careful monitoring, medication and psychotherapy.

“With proper management, people can live fully functional lives,” she assures.

The doctor advises against skipping doses, noting that “it is very dangerous. A single relapse can erase months of stability”.

“Treatment involves medication, mood stabilisers, antidepressants, antipsychotics and psychotherapy. Both are necessary,” she says.

“We use mood stabilisers, such as lithium or valproate, sometimes antipsychotics during severe mania and antidepressants during depression.

“But every patient responds differently, so constant monitoring is necessary. Skipping medication can cause a relapse.”

Cautioning against stigma, Dr Kamwale warns that “it kills faster than the illness”.

“Many patients stop taking medication because their families believe they are bewitched,” she adds.

“Others lose jobs because employers don’t understand. It is clear that education is our most powerful medicine.”

She also notes that the country has a shortage of psychiatrists and most are in urban areas, disadvantaging patients in rural areas.

“Kenya has a severe shortage of psychiatrists. Most are in Nairobi. Patients in rural areas rarely access proper care,” she says.

MENTAL HEALTH LANDSCAPE

According to the Kenya Psychiatric Association, one in every four Kenyans is likely to experience mental illness at some point in their lives.

Bipolar disorder, though less common than depression and anxiety, remains significantly underdiagnosed.

With fewer than 200 practising psychiatrists serving a population of more than 50 million, access to care is a daily struggle.

According to Ministry of Health guidelines, Kenya needs 1,400 more psychiatrists, 7,000 more psychiatric nurses and 3,000 more psychologists.

In March, a detailed report forwarded to the UN ahead of the fourth cycle of the peer review mechanism showed that the government only allocates 0.001 per cent of the national health budget towards mental health annually.

The globally recommended level is $1.16 (Sh150) per capita, but Kenya is spending $0.0012 (less than a cent), the report sent to Geneva showed.

Families often bear the burden, with patients relying on relatives for financial, emotional and physical support.

Despite the hardships, both Samuel and Patience insist on hope.

Samuel maintains a steady routine of medication, therapy, exercise and healthy living. He is raising two daughters with his wife and does advocacy work to support others.

“For anyone diagnosed with bipolar or any mental illness, take care of yourself. Follow the doctor’s instructions,” he says.

“Surround yourself with supportive people. There is hope. Recovery is possible.”

Patience echoes this message. “At first I thought my life was over,” she says.

“But now I know it’s just a part of me. I am still me. I can work, I can love, I can dream. I just have to manage it. And I want others to know it’s possible.”

Samuel Boiyo and Patience Kyalo’s stories highlight both the challenges and the possibilities of living with bipolar disorder in Kenya.

Their journeys convey one truth: bipolar disorder is not the end of life’s story. It is a chapter that, with courage, care and community, can be managed.

As Samuel puts it: “Everyone has a mental illness to some degree. It is only the severity that differs. You are not alone. And you can live well. There is hope for tomorrow.”