In many Kenyan households, the day begins with

the search for water.

The task often falls on women and girls who spend

hours walking to far-off sources, queuing at taps, and carrying heavy

containers back home.

This limits their opportunities for

education, work, or even rest.

For

decades, development organisations have argued that bringing water and

sanitation closer to people’s homes frees up time, especially for women and

girls.

A new international study now shows just how much

time can be reclaimed, and the difference it makes for families in Kenya and

other developing countries.

The research, No Time to Waste: A Synthesis of

Evidence on Time Reallocation Following Water, Sanitation and Hygiene

Interventions, was published in the Journal of International Development in

2025.

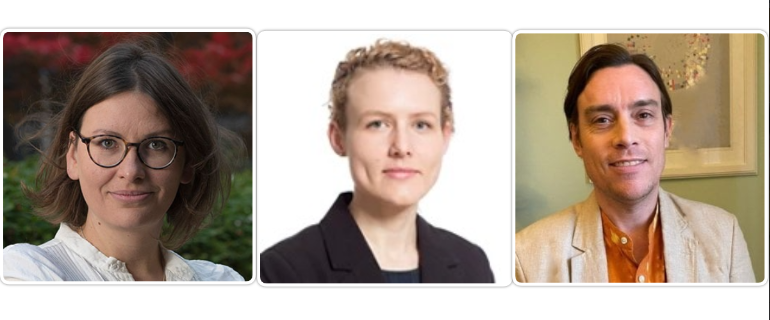

The research was co-authored by Hugh Sharma

Waddington, a researcher at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical

Medicine; Sarah Dickin, a researcher at Uppsala University;

and Biljana Macura, a researcher at the Stockholm Environment Institute

(SEI).

After analysing more than 30,000 records, the

authors identified 41 relevant projects across Africa, Asia, Latin America, and

the Middle East.

Taken together, the evidence shows that when clean water and sanitation are available close to home, households reclaim nearly a full working day each week.

Hours won back

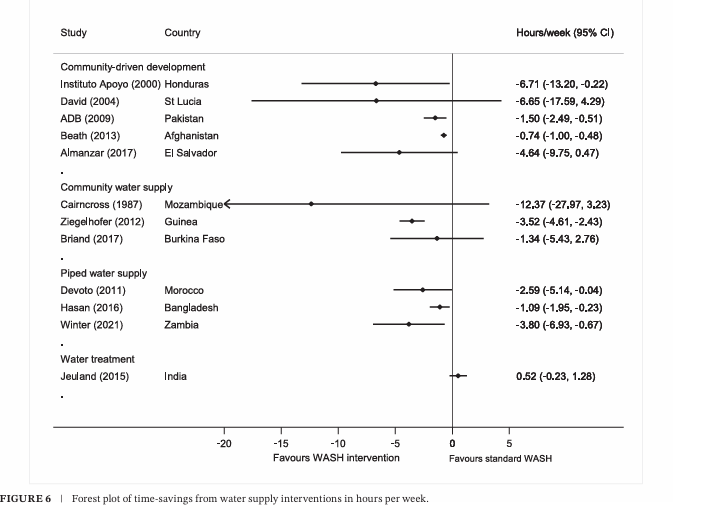

On average, water supply interventions cut

collection times by 15 minutes per trip. For sanitation, the average saving was

three minutes.

Because families make multiple trips each day,

the differences add up quickly.

The study found that households gained around 8

hours per week after water supply improvements and 3.5 hours after sanitation

improvements.

In Kenya and other African countries, the effect

was striking as families saved an average of 21 minutes per trip, compared with

just 4 minutes in Asia.

In Nairobi’s settlements, installing community

standpipes reduced collection times from more than half an hour to less than

ten minutes.

In rural areas, roof catchments and new pipelines

cut journeys by up to an hour.

The scale of these benefits also varied across regions.

In sub-Saharan Africa, where nearly half the

population still relies on collecting water from outside the home, the average

time saved per trip was 21 minutes.

Elsewhere in Central and Southern Asia, where

about a quarter of people rely on collection, the savings were just 4 minutes.

In Northern Africa and Western Asia, the figure

was 12 per cent of households, while in Latin America and the Caribbean it was

only 3 per cent.

These contrasts underline how urgent the problem

remains in Africa compared with other regions.

The burden of collection falls most heavily on

women and girls. Globally, seven in ten households rely on them for the task,

compared with just over a quarter for men.

With water closer to home, women face less

physical strain and fewer safety risks, and they have more opportunities to

rest, work, or participate in community life.

“When women and girls supply part of the water

infrastructure through lengthy trips to collect water, this wastes their potential

to achieve other goals, for example regarding education and work, holding

society back,” Dickin said.

She added that the findings can help stakeholders

advocate for more investment in water and sanitation, noting that these

services are not only critical for children under five but also provide wider

societal benefits.

“Time savings mean greater dignity and people

having more time to pursue their goals,” she said.

Education benefits

One of the clearest gains is in education as the

study found medium-sized effects of water supply interventions on girls’ school

attendance, but no significant effects for boys, suggesting that girls benefit

directly when they are freed from the responsibility of water collection.

The research also found that extending municipal

piped water to households previously without it saved about an hour per trip.

Even installing community supplies in rural areas

produced similar gains during the rainy season.

The educational link is confirmed by the

data,Sharma explained that the time savings are substantial.

“We found

savings of around an hour per trip from extending municipal piped water to

households that previously lacked them, but even installing community water

supplies in rural areas saved around an hour per trip in the rainy season,” he

explained.

According to him, when water is collected daily

or even multiple times per day, the lost time quickly adds up.

“There is a strong empirical relationship between

water availability at home and girls' school attendance, partly because girls

no longer have to fetch the water,” he said.

The study concluded that when water is available

at home, girls spend more time in classrooms instead of walking to distant

points.

The ripple

effect is significant. Each lesson attended adds up over the years, shaping

futures that might otherwise have been lost to daily chores.

The report gave examples from earlier

interventions that show the scale of change possible.

In Mozambique in the 1980s, one project cut round-trip

trips from five hours to just ten minutes. In Ghana and Kenya, more recent

projects reduced trips to under an hour, while in Eswatini a community stand

post halved collection times.

In urban Kenya, the adoption of mobile billing

systems allowed people to pay for water using their phones rather than queuing

at banks, saving significant hours each week.

In parts

of Latin America, piped household connections meant that some families spent no

time at all fetching water while their neighbours without connections still

did.

Solutions that work

The study showed that not all interventions have

the same effect. Some water treatment projects or efforts to avoid contaminated

wells added a few minutes per trip.

However, larger infrastructure projects created

far greater benefits.

Piped water connections and community standpipes

produced the most significant time savings, cutting journeys dramatically

across Kenyan households.

Sharma stressed that governments should focus on

solutions that people are likely to use.

“Governments should prioritise providing what

their citizens need and are likely to use, like technology that saves drudgery,

unnecessary risk, and indignity,” he said.

“For example, having water in quantity,

preferably more than 50 litres per person and day, for personal and domestic

hygiene and drinking purposes, and also working with communities to provide

sanitation for every household.”

He added that such investments are pro-poor

growth strategies.

They free up sufficient amounts of time for

schooling or work and, according to World Bank estimates, generate millions for

the economy.

The study also pointed to Kenya’s use of mobile

billing systems for water services as an example of innovation. By enabling

families to pay through their phones, queues at water points were shortened,

saving households even more time.

In contrast, the evidence on how adults use the

time saved is less consistent across all regions and demographics, reflecting a

gap in research focus.

Policy implications

The researchers emphasised that time should be

treated as a core outcome when evaluating water and sanitation projects,

alongside health.

Macura noted that this shift is overdue.

“Policymakers and practitioners should view our

findings as a call to strengthen measurement of time use in WASH and to support

new data collection on how time savings are reallocated, including to leisure,”

she said.

The report also highlighted gaps in evidence.

Only 10 of the 41 studies broke down results by sex, and only seven included

children. Just five focused specifically on women, children or vulnerable

groups.

Two examined programmes for people with

disabilities, while none looked at pastoralist households or gender minorities.

The researchers stressed that these omissions are

serious, since time savings may be most important for these groups.

Additionally, it was noted that facilities such

as handwashing stations or menstrual waste receptacles were overlooked, even

though they are essential for health and could potentially save time.

The evidence also ties into Kenya’s development

agenda. Reducing the hours families spend collecting water directly supports

progress toward Sustainable Development Goal 6 on clean water and sanitation,

and Goal 4 on quality education.

Climate change adds another layer of urgency as

the study warned that rising temperatures and droughts could increase water

collection times by up to 30 per cent globally, and by as much as 100 per cent

in some regions.

effective interventions, women and girls will

bear the heaviest burden.

Yet challenges remain as nearly half of Kenyan

households still rely on sources outside their homes, often at a considerable

distance.

In rural areas, families still spend hours on

water collection each day.

The researchers call for governments and donors

to expand investment in piped systems and safe household toilets.

They stress that projects should be designed with

women and girls at the centre, since they bear the heaviest burden.

Time as opportunity

The hours saved ripple across households as women

who no longer spend mornings walking for water can take on other

responsibilities or simply rest.

Girls who no longer fetch water can remain in

school.

Beyond individual households, the benefits likely

spill over into communities and economies.

Time freed from collection creates the

opportunity for more hours for income-generating work, better meals prepared at

home, or participation in civic life, though further dedicated research on

adult time reallocation is still needed to quantify these broader societal

benefits.