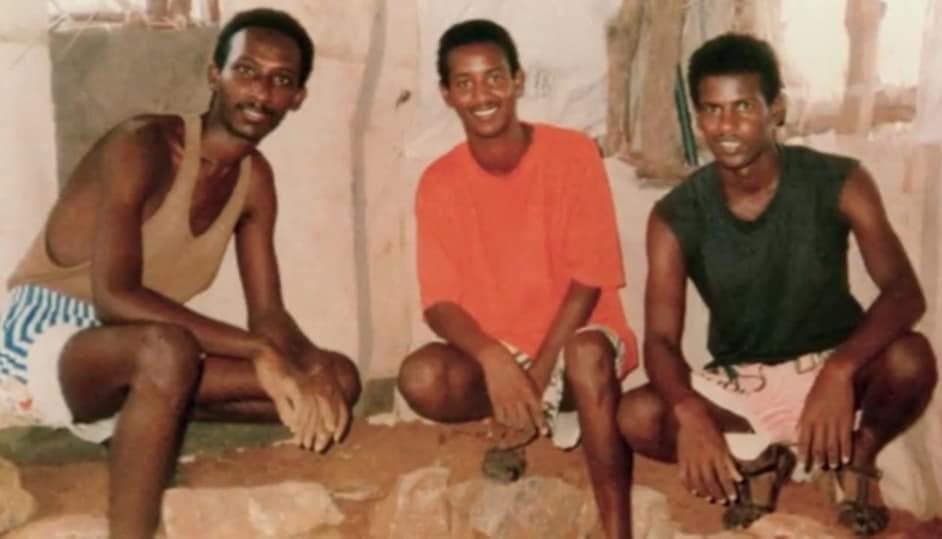

Paulos Eyasu, Isaac Mogos and Negede

Teklemariam, three Jehovah's Witnesses held in Eritrea | JW.org/JW.org

Paulos Eyasu, Isaac Mogos and Negede

Teklemariam, three Jehovah's Witnesses held in Eritrea | JW.org/JW.orgThe African Commission on Human and

Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR) has directed the State of Eritrea to compensate three

Jehovah’s Witnesses who were illegally detained for 26 years, marking one of

the strongest continental rebukes yet of the country’s long-standing religious

persecution policies.

In a communication issued on November 4,

2025, the Commission urged Eritrea to “take measures to compensate the victim

for the prejudice they suffered due to the unjustified prolonged detention,

torture, agony and inability to make a living for 26 years.”

The decision follows a petition filed on

behalf of Paulos Eyassu, Isaac Mogos, and Negede Teklemariam—three Eritrean

Jehovah’s Witnesses arrested in 1994 for refusing military service on grounds

of conscience and for declining to vote in the 1993 independence referendum.

The three men were among the

longest-serving religious prisoners of conscience on the African continent. For

more than two decades, they were held without charge, trial, legal

representation, or access to their families.

Their case has come to symbolize the

Eritrean government’s harsh treatment of citizens who refuse compulsory

military service, which in Eritrea functions as an indefinite national service

program widely criticized by human rights bodies.

The Commission’s ruling comes 31 years

after the Eritrean government issued a decree revoking the citizenship of

Jehovah’s Witnesses, a move that effectively rendered thousands stateless.

The decree was based on the group’s

conscientious objection to military service and refusal to participate in the

referendum that formalized Eritrea’s independence from Ethiopia.

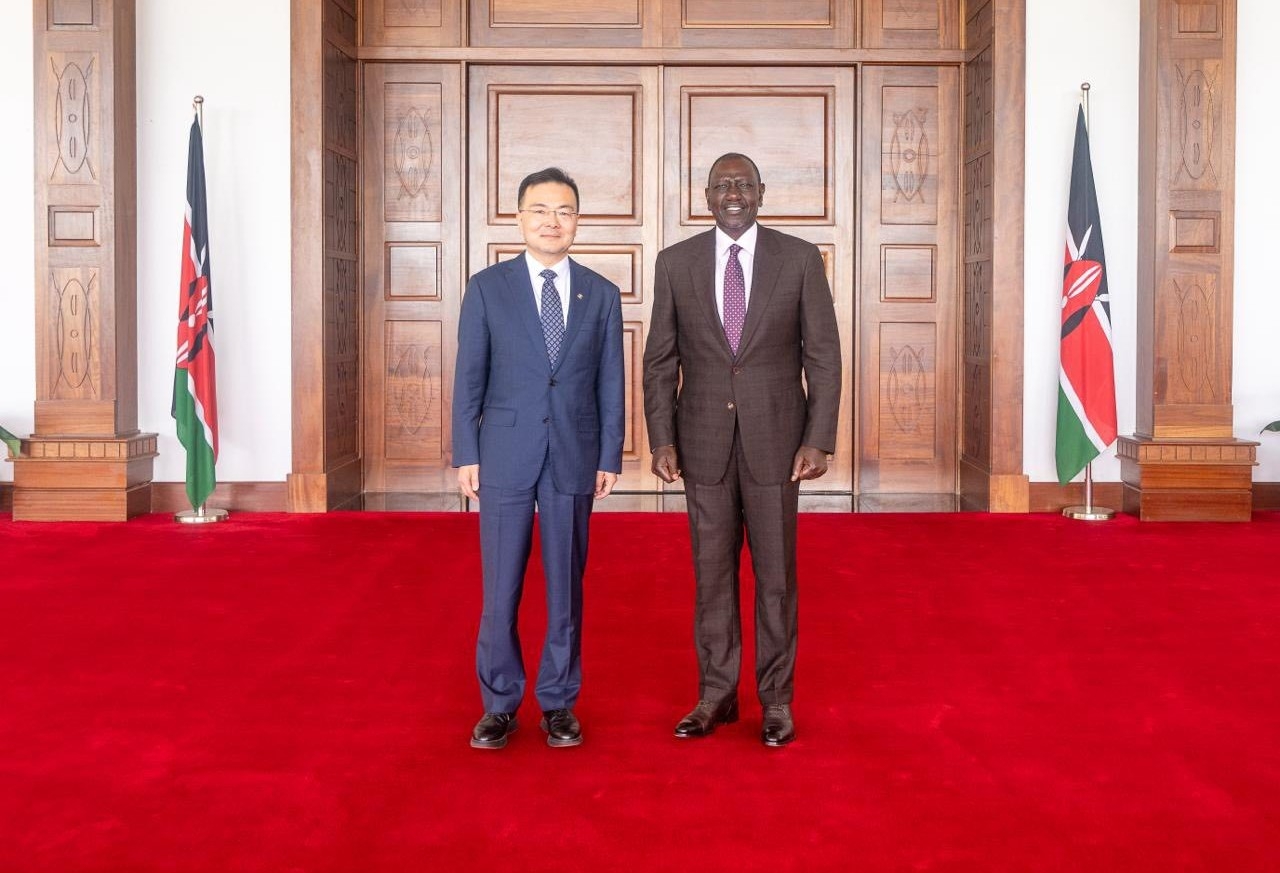

Noah Munyao, Secretary General of the

African Association of Jehovah’s Witnesses./HANDOUT

Noah Munyao, Secretary General of the

African Association of Jehovah’s Witnesses./HANDOUTSince then, Jehovah’s Witnesses have

faced systemic discrimination, including denial of employment, education,

business licenses, and national identity documents—restrictions that have made

many of them “invisible under the law.”

Human rights observers say that while

Eritrea claims to maintain religious tolerance, only four faith groups are

officially recognized.

Jehovah’s Witnesses fall outside this

list and have been subject to waves of arbitrary arrests and prolonged

detentions.

Rights groups have repeatedly accused

Eritrea of holding detainees in inhumane conditions, including shipping

containers, underground cells, and remote military camps.

“For over three decades, Jehovah’s

Witnesses in Eritrea have endured systemic discrimination and statelessness

simply for living according to their conscience,” said Noah Munyao, Secretary

General of the African Association of Jehovah’s Witnesses.

He called on the Eritrean government to

restore their citizenship and “uphold the basic human rights and dignity of all

its people.”

The ACHPR ruling aligns with findings of

the 2025 Religious Freedom Report, which criticized Eritrea for criminalizing

religious activities of minority groups and maintaining one of the most

restrictive environments for freedom of belief globally.

The report noted that conditions “remain

critically poor” under the country’s authoritarian political system, where

unrecognized religious groups are frequently targeted.

Although Eritrea has released small

groups of religious prisoners in recent years—including several Jehovah’s

Witnesses in 2021 and 2023—dozens remain behind bars.

Paulos Eyasu, Isaac Mogos and Negede

Teklemariam, three Jehovah’s Witnesses held in Eritrea | JW.org/JW.org

Paulos Eyasu, Isaac Mogos and Negede

Teklemariam, three Jehovah’s Witnesses held in Eritrea | JW.org/JW.orgAccording to the African Association of

Jehovah’s Witnesses, 64 adherents are currently imprisoned, including 14 aged

over 60.

International human rights organisations

say the ACHPR decision adds new pressure on Eritrea ahead of upcoming

continental reviews of its human rights commitments.

The ruling also strengthens calls from

the global community of Jehovah’s Witnesses for the release of all remaining

detainees, the restoration of citizenship to those stripped of nationality, and

compliance with African and international human rights norms.

While Eritrea has not responded publicly

to the Commission’s directive, human rights advocates hope the decision will

set a precedent for accountability in a country where judicial recourse is

extremely limited.