Once hailed as part of a new generation of reformist African leaders, Eritrea's president, who recently marked 32 years in power, has long defied expectations.

Isaias Afwerki now spends much of his time at his rural residence on a dusty hillside some 20km (12 miles) from the capital, Asmara.

With the cabinet not having met since 2018, all power flows through him, and like a potentate he receives a string of local officials and foreign dignitaries at his retreat.

It is also a magnet for ordinary Eritreans hoping in vain that Isaias might help them with their problems.

The 79-year-old has never faced an election in his three decades in power and there is little sign of that changing any time soon.

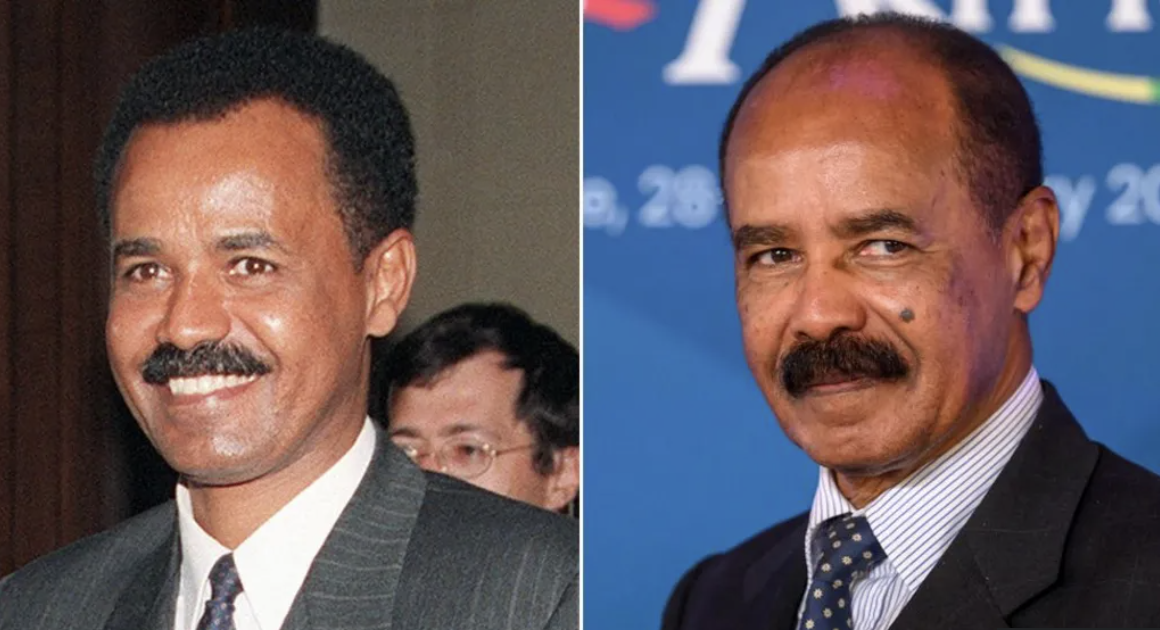

But things looked very different in the 1990s.

Isaias was 45 when, as a rebel leader, his Eritrean People's Liberation Front (EPLF) defeated Ethiopia in 1991. Those who fought in the war are remembered each year on Martyrs' Day, 20 June.

Tall and charismatic, he inspired hope both at home and abroad.

In 1993, following formal independence, Isaias appeared on the international stage as head of state for the first time.

It was in Cairo, where he attended a continental leaders' summit, that he lambasted the older generation of African leaders "who wanted to stay in power for decades".

He vowed that Eritrea would never repeat the same old failed approach and promised a democratic order that would underpin the social and economic development of his people. His stance won him plaudits from Eritreans and diplomats alike.

In 1995, after inviting the Eritrean leader to the Oval Office, US President Bill Clinton expressed appreciation for the country's strong start on the road to democracy.

Eritrea had just begun drafting a new constitution expected to establish the rule of law and a democratic system.

Isaias was supposed to be a "transitional president" until a constitutional government was elected. The new constitution was ratified by a constituent assembly in May 1997.

But just as Eritreans and the world were expecting national elections in 1998, war broke out between Eritrea and neighbouring Ethiopia over a disputed border.

Isaias was accused of using the war as a justification to postpone the elections indefinitely.

He had promised a multiparty democratic system and his resolve was tested after a peace agreement was reached in 2000.

Several of his cabinet ministers, including former close friends and comrades-in-arms, began to call for reform.

In an open letter issued in March 2001, a group of senior government officials, who later became known as the G-15, accused the president of abusing his powers and becoming increasingly autocratic. They called for the implementation of the constitution and national elections.

Starting from the mid 1990s, Eritreans had tasted some freedom, with emerging newspapers carrying critical voices — including from within the ruling party, that had been renamed the People's Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ).

The country seemed to be on a slow path towards democratisation.

In a single morning, the authorities shut down all independent newspapers, effectively silencing critical voices. Many editors and journalists were detained and never seen again.

The hopes of many Eritreans were dashed.

"I had never had any intention of participating in political parties," he said in April 2001.

He also described the democratic process as a "mess", saying that the PFDJ was "not a party. It is a nation".

The silencing of critics and the failure to hold elections, earned him and his country pariah status.

In 2002, he unofficially dissolved the transitional assembly that was meant to hold him accountable and in effect did the same with the cabinet in 2018.

Many wonder why the independence hero took such a repressive turn.

"He systematically weakened and removed leaders with public legitimacy and struggle credentials who could challenge his authority."

The proposal to write a new constitution may have been triggered by an attempted coup by senior military officers in 2013.

Realising the attempt was failing, they tried to broadcast a call to implement the 1997 constitution and release political prisoners. But security forces pulled the plug mid-broadcast.

Zeraslasie Shiker, a former diplomat, left his post in Nigeria and sought asylum in the UK. His boss, Ambassador Ali Omeru, a veteran of the independence war, was later detained and remains unaccounted for.

"The indefinite suspension of Eritrea's constitution and the collapsing of government institutions into the office of the president must be understood in this context."

The country's economy has "struggled", according to the World Bank's assessment last year.

Isaias himself acknowledged problems in an interview with state TV in December last year.

Isaias also refuses humanitarian aid, citing fears of dependency that would undermine his principle of "self-reliance".

Disillusioned by the lack of political progress and exhausted by forced conscription and state violence, many risk their lives to escape in search of freedom.

In his independence day speech last month, Isaias gave no hint of any of the changes many Eritreans hope to see. There was no mention of a constitution, national elections or the release of political prisoners.

Despite criticism at home, President Isaias retains support among parts of the population, particularly within the military, ruling party networks and those who view him as a symbol of national independence and resistance against foreign interference.

As frustration grew in Eritrea, Isaias retreated from Asmara in 2014 to his home that overlooks the Adi Hallo dam whose construction he closely supervised.

An apparent attempt to groom his eldest son to succeed him was reportedly blocked at a 2018 cabinet meeting, since when no further meetings have been held.

"The president's office is what's holding the country from collapse," warns Mr Zeraslasie.

For now, however, Isaias remains firmly in control, while Eritreans continue their long and anxious wait for change.

![[PHOTOS] Ole Ntutu’s son weds in stylish red-themed wedding](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcdn.radioafrica.digital%2Fimage%2F2025%2F11%2Ff0a5154e-67fd-4594-9d5d-6196bf96ed79.jpeg&w=3840&q=100)