AI Illustration

AI IllustrationThe recent directive by the Nairobi

County Government granting its female employees two days of paid menstrual

leave each month has ignited fresh debate and discussion not only in Kenya, but

globally.

This move by Nairobi places it among

a growing, yet still relatively small, cohort of regions and nations exploring

how best to support women in the workplace during their menstrual cycles.

Menstrual leave — a formal workplace

entitlement that allows people to take time off for disabling period pain or

other menstrual symptoms — exists in only a handful of countries, and its

real-world impact has been mixed.

At its core, menstrual leave

acknowledges that for many women, menstruation is not merely an inconvenience

but can be a debilitating experience accompanied by severe pain, fatigue, and

other symptoms that make regular work difficult, if not impossible.

While the concept has existed for

decades in some parts of the world, its global prevalence remains sporadic,

marked by a patchwork of successes, challenges, and ongoing resistance.

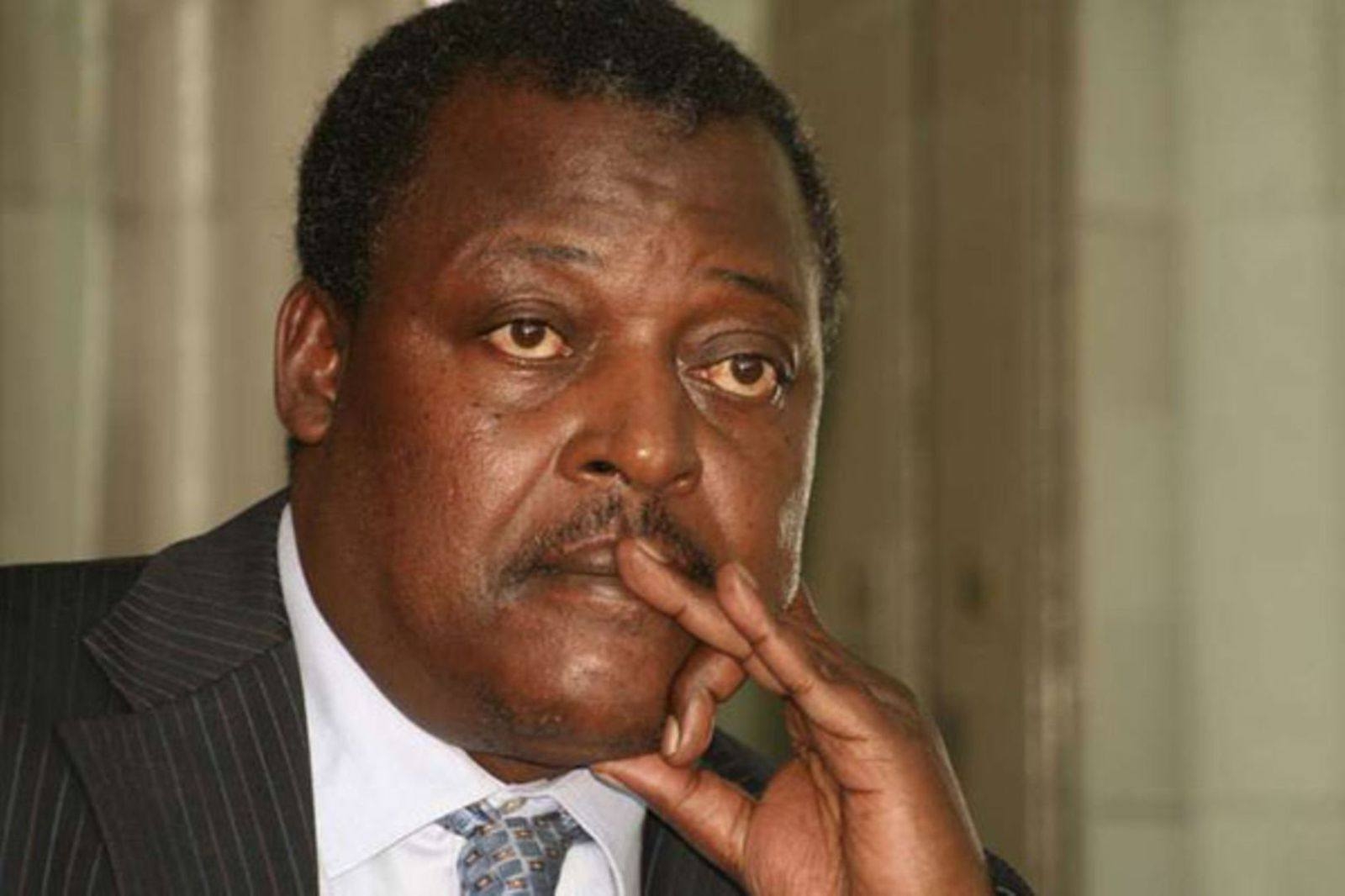

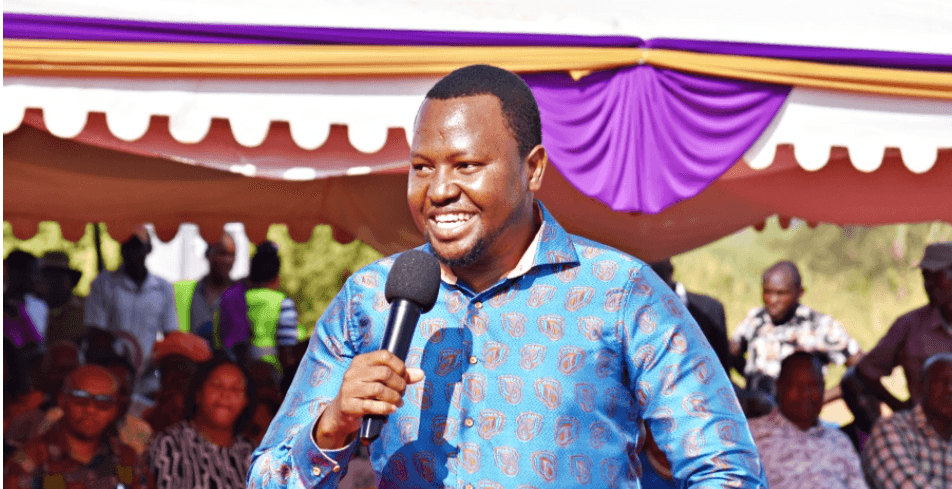

Nairobi’s directive, announced by

Governor Johnson Sakaja, represents a significant moment for workers’ rights in

Africa.

“Female employees will be entitled

to two days of paid menstrual leave every month, without any deduction from

their annual leave,” Sakaja declared, emphasising the county’s commitment to

supporting its female workforce.

The move aims to address the silent

suffering many women endure, often forcing them to work through severe

discomfort for fear of being perceived as weak or less committed.

The implementation of this policy in

Nairobi will be closely watched. Advocates hope it will set a precedent for

other counties and even national governments across Africa, a continent where

cultural norms often discourage open discussion about menstruation.

The idea of menstrual leave is far

from new. Some countries have had policies in place for decades, while others

are only beginning to grapple with the concept.

Japan

Japan is one of the earliest

adopters, having introduced menstrual leave — known as seirikyuuka — as

far back as 1947.

This post-World War II labour law

recognised the physical toll menstruation could take on women working in

factories and other demanding environments.

However, while the entitlement is

enshrined in law, its use has declined significantly over the years.

Data from Japan’s Ministry of

Health, Labour and Welfare shows that fewer than one per cent of eligible women

take menstrual leave.

Indonesia

Indonesia introduced menstrual leave

in its labour law in 2003, allowing female employees up to two days of paid

leave per month if they experience pain during menstruation.

However, as in Japan, implementation

has been inconsistent.

Many companies require medical

certificates, creating additional barriers, while others simply fail to comply

with the law.

Spain

In a landmark decision in February

2023, Spain became the first European country to introduce paid menstrual

leave.

The law allows women experiencing

debilitating periods to take up to three days of paid leave per month, with the

possibility of extension, subject to a doctor’s note.

The move was celebrated by women’s

rights advocates as a progressive step. Spain’s Equality Minister, Irene

Montero, hailed the law as “a great step forward for the equality and health of

women.”

Zambia

Zambia has had “Mother’s Day” — a

monthly day of menstrual leave — enshrined in its labour laws since 1996.

Unlike in some other countries,

implementation has often been cited as relatively successful, with many women

regularly using the entitlement.

This success is partly attributed to

greater cultural acceptance of the leave and less stigma attached to its use.

What works, what doesn’t

Global experiences with menstrual

leave offer valuable insights into effective implementation and common

pitfalls.

Countries with higher uptake tend to

have clear, unambiguous policies that are well communicated to both employers

and employees. Z

ambia’s “Mother’s Day,” for example,

is explicitly defined and widely understood, making it easier for women to

access the entitlement without confusion.

Cultural acceptance also plays a

critical role. In workplaces where menstruation is openly discussed and not

treated as a taboo, women are more likely to use menstrual leave without fear

of judgement.

Educational initiatives and visible

leadership support have been shown to reduce stigma and normalise menstrual

health as a legitimate workplace issue.

Policies that do not require medical

certificates for short-term menstrual leave have also proved more effective.

Requiring a doctor’s note for a

routine biological process can create unnecessary financial and logistical

barriers, particularly for low-income workers.

Conversely, stigma and

discrimination remain the most significant challenges. Even where policies

exist, many women are reluctant to take menstrual leave out of fear of being

perceived as less productive or unreliable.

“Many women are afraid that taking

menstrual leave will negatively impact their career progression or lead to

discrimination from employers,” observes Dr Okamura.

Weak enforcement and low awareness

further limit impact. In countries such as Indonesia, where the law exists but

is poorly enforced or communicated, many employees remain unaware of their

rights.

Employer resistance has also

hindered implementation, often driven by misconceptions that all women will

take the leave every month — a fear evidence suggests is largely unfounded.

Finally, policies that pressure

women to prove their level of suffering through excessive documentation or

invasive questioning have been counterproductive, deterring access rather than

promoting dignity.

The path forward

For menstrual leave to be truly

effective, it must be supported by robust educational campaigns to

de-stigmatise menstruation and ensure both employers and employees understand

the policy. Strong enforcement mechanisms are essential to prevent the

entitlement from existing only on paper.

Equally important is visible

leadership commitment to creating workplaces where women feel safe and

supported when using menstrual leave.

Flexibility remains key, recognising

that menstrual experiences vary widely and that a one-size-fits-all approach

may fail to meet individual health needs.