What the government

sees as a necessary economic strategy has handed the opposition a ready-made

rallying call that the administration is auctioning the country’s most-prized

and critical assets to fund its survival.

The latest storm

surrounds the planned sale of 15 per cent of the government stake in Safaricom

to Vodafone.

The transaction,

expected to raise about Sh240.5 billion, is designed to seed the National

Sovereign Fund and the National Infrastructure Fund.

The two funds are

central to the financing of Ruto’s flagship projects as he races toward the

next polls.

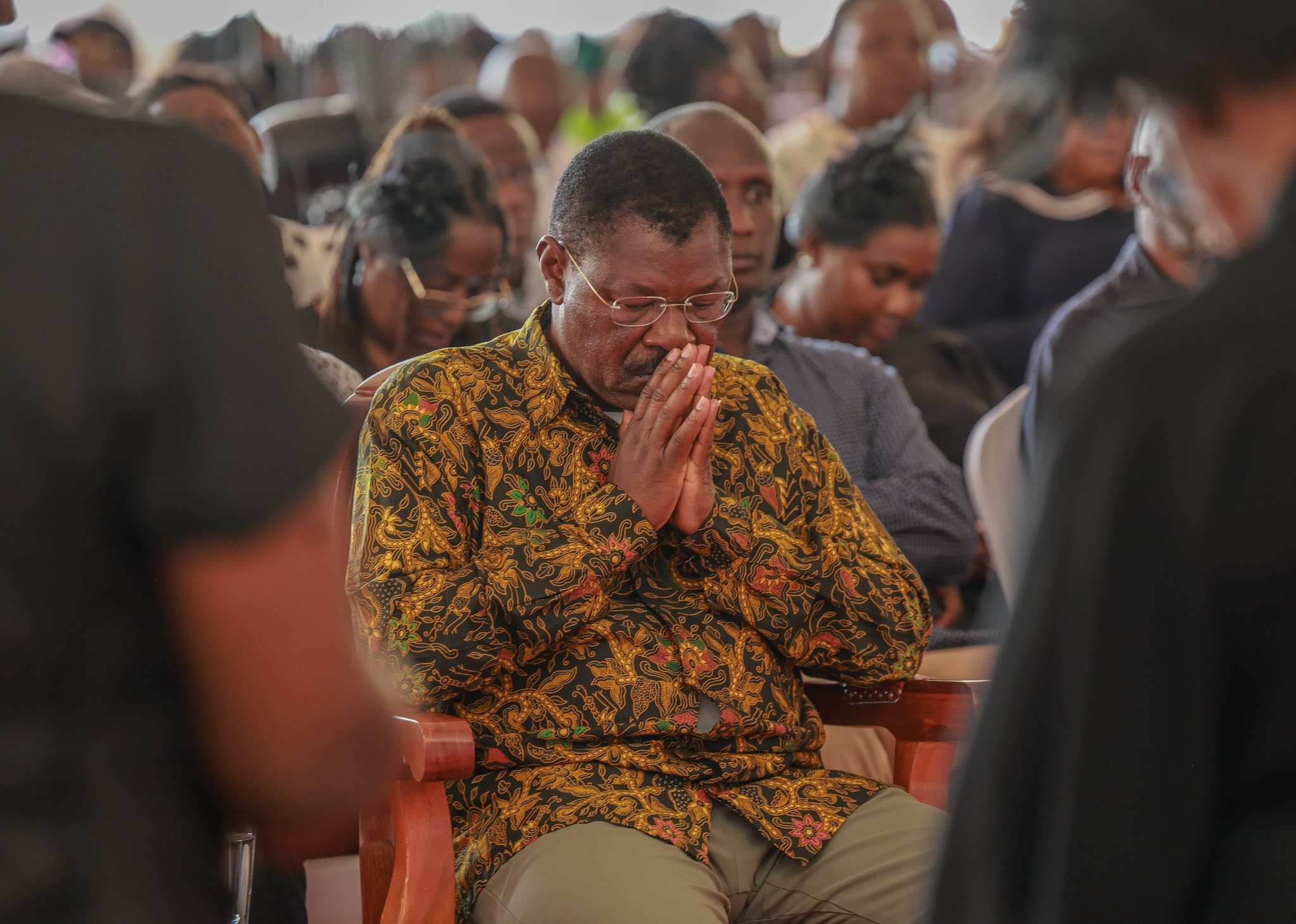

Opposition figures,

among them, former Deputy President Rigathi Gachagua and Wiper leader Kalonzo

Musyoka, have strongly criticised the privatisation drive.

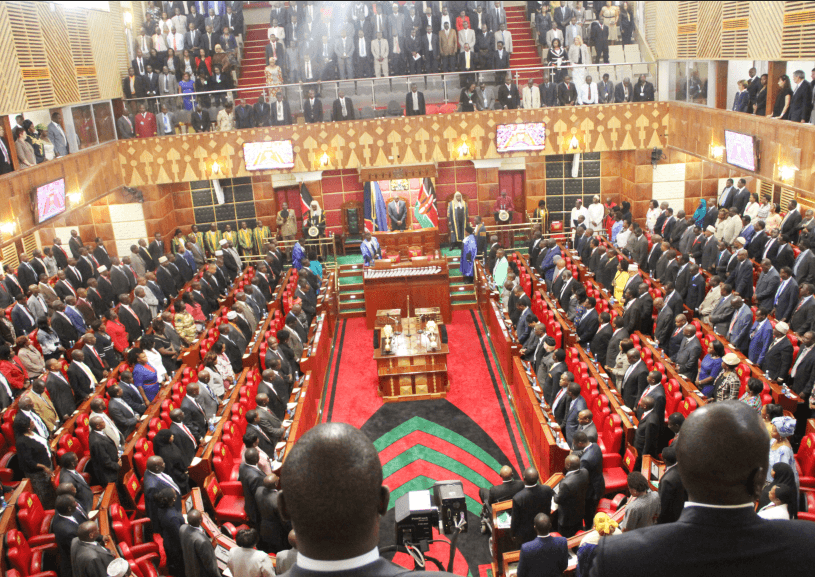

The criticism has

gone beyond the United Opposition camp, drawing interest from legislators such

as Ndindi Nyoro (Kiharu), Peter Salasya (Mumias East) as well as the

ODM-aligned Caroli Omondi (Suba south and Babu Owino (Embakasi East).

Critics accuse the

government of undervaluing the shares and excluding Kenyans from the “opaque”

sale yet they are the owners of the stake.

“We know as they try

to sell this parastatal without public participation, which is a constitutional

requirement, it is simply because someone somewhere wants a cut,” Kalonzo said

last Sunday.

Gachagua used his

criticism to campaign for the opposition, saying the country must be liberated

from the current Kenya Kwanza administration.

“The way things are

going, all national institutions [parastatals] are being sold,” Gachagua said.

The leaders have

vowed to block the transaction.

The backlash on the

proposed Safaricom share sale comes hot on the heels of the debate on the

privatisation of the Kenya Pipeline Company.

The KPC sale

controversy evolved into a heated political battle over the government's plan

to privatise the strategic parastatal for funding.

Just like the

Safaricom share sale, the bid to privatise KPC faced strong opposition from the

public and lawmakers, citing the same concerns as the telco deal: lack of

public participation, potential corruption and economic sabotage.

Even though MPs

approved the sale, the High Court issued a temporary injunction against the

deal due to legal and transparency concerns.

The executive also

launched a spirited fight defending the sale, with President William Ruto and

Prime CS Musalia Mudavadi saying the privatisation would help the

administration raise funds to “transform Kenya”.

The opposition,

however, would hear none of that. Kalonzo warned against the sale of the

“strategic asset”, which he said is vital to the country’s energy sector.

“Ruto, don’t dare

sell the Kenya Pipeline Company,” he said in August.

“If you attempt to

fast-track the auction despite the court orders, we will come after you just

like we did in the Adani-JKIA issue and stop it.”

However, the

President indicated his full focus on the sale during his visit to Uganda in

early December.

Framing it as part

of a broader regional investment plan, he told President Yoweri Museveni that

his country would get a stake at KPC as the government divests 65 per cent of

its ownership.

The Adani-JKIA deal

was also controversial, with the opposition winning round one of the battle

after Ruto dropped the $2.5 billion takeover deal, citing graft following “new

information provided by investigative agencies and partner nations [the US]”.

Equally, a separate

30-year, $736-million PPP deal that the Adani Group firm signed with the

Ministry of Energy to construct power transmission lines was cancelled.

The sale of sugar

companies also caused political heat, especially in Western Kenya, with leaders

from the region opposing the sale. They cited a lack of transparency, a risk to

livelihoods and a failure to follow proper procedures.

While the Ruto

government is pushing for the sales as part of its economic strategy to

revitalise the economy, the opposition argues such decisions will render the

country “dry” of assets and has vowed to revoke transactions if they assume

office in 2027.

The perceived

economic consequences of these sales are thus expected to be central in the

campaign promises and manifestos.

Political analysts

opine that the United Opposition will do everything to kill sale of Safaricom

shares and other parastatals in its bid to slow down the government’s delivery

of critical projects.

They believe the

infrastructure fund enabling earmarked projects would give Ruto a massive edge

in 2027.

Political risk

analyst Dismas Mokua says it has become the norm for every action by the

President to draw criticism, especially from the opposition.

He said the option

to sell shares in parastatals has been necessitated by the shrinking options

the government has to finance its programmes.

“The government

cannot increase taxes as it will draw uproar from Kenyans,” Mokua said.

“It cannot borrow

domestically as it will be accused of crowding out the private sector. And if

it borrows externally, that will also be a problem.”

The analyst,

however, noted that the criticism the government is facing is lack of a

strategic communication plan to explain its intentions.

He further adds that

the trust deficit in the country is not helping the administration.

The debate also taps

into general public sentiment about national ownership and the efficient use of

public resources, as the Ruto government faces criticism on corruption and

management of the economy.

In the past, key

national debates have ended up being central to campaign messaging.

They include the Mau

Forest evictions that arguably dented then Prime Minister Raila Odinga’s

presidential campaign, the ICC cases, electoral integrity in 2017 and the

economy in 2022, which Ruto capitalised on by campaigning with the hustler

narrative.