Farmers in Mwala subcounty in Machakos county are trained by researchers from KALRO on how to scout and monitor for fall armyworms in the farm /AGATHA NGOTHO

Farmers in Mwala subcounty in Machakos county are trained by researchers from KALRO on how to scout and monitor for fall armyworms in the farm /AGATHA NGOTHOFor many years, Catherine Mwanzia, a farmer from Masii ward, Machakos county, has battled pest infestations on her maize farm.

But none has been as devastating as the fall armyworm.

“I have been farming for many years and encountered many challenges,” she said.

“The biggest one has been pests. They eat everything and controlling them costs us so much money because we have to keep buying chemicals.”

The pest can wipe out an entire maize field.

“To avoid total losses, I used ash to control it since chemicals were too expensive for me. But it was time consuming because I had to apply the ash on each plant.”

Despite her efforts, the method was exhausting and largely ineffective, as she still suffered significant losses.

She has now adopted better pest control practices thanks to training from researchers at the Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organisation (Kalro). They include how to scout for pests and which biocontrol is available in the market.

Maize infested with the fall armyworm /AGATHA NGOTHO

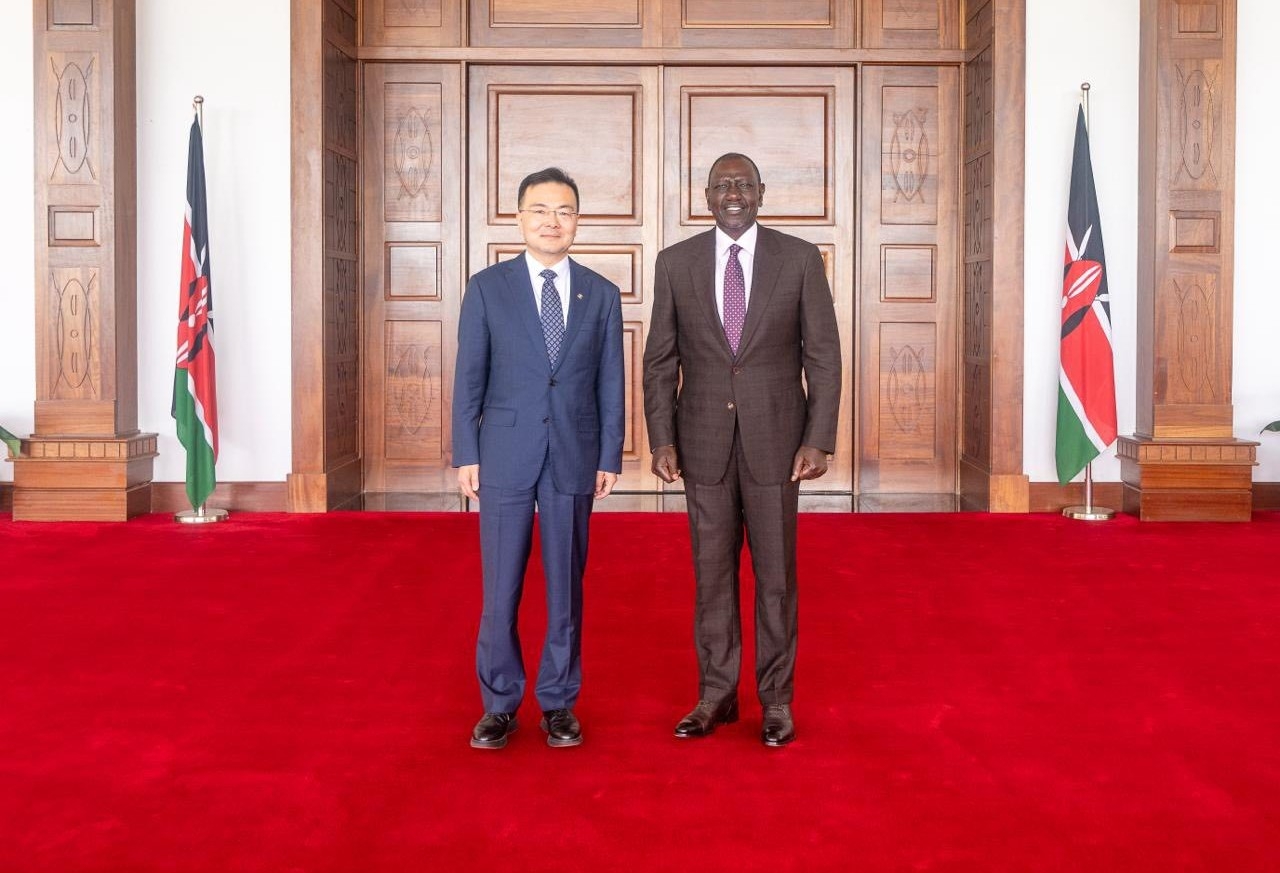

Maize infested with the fall armyworm /AGATHA NGOTHOMwanzia is among farmers who have benefited from a pest management programme run by Kalro in partnership with the Korean government under the Korea-Africa Food & Agriculture Cooperation Initiative (Kafaci).

“Before, I could harvest less than five bags per acre, but after working with the agricultural officers, I harvested more than 10 bags, and this was a huge difference.”

Through the initiative, farmers are trained on integrated pest management to reduce overreliance on chemical pesticides.

“We were taught how to plant, manage the crops and control pests without depending on chemicals,” she said.

“Now, we share what we’ve learned with our neighbours.”

Dr Kasina Muo, a researcher at Kalro, said the fall armyworm has become one of the most destructive pests on the continent, affecting nearly all maize-growing areas in Kenya.

The fall armyworm invaded Kenya in 2017 and has since ravaged maize farms across the country, leaving many farmers counting losses.

“This pest has been a very serious problem since 2017,” he said.

“You can hardly grow maize today without using pesticides.”

He said overuse of pesticides poses major risks to human health, wildlife and the environment. The Kafaci programme, he explained, focuses on promoting biological control methods.

“Every living organism has a natural enemy and so do pests,” he said.

“We are using beneficial fungi and parasitoid wasps that attack the fall armyworm. Some wasps lay eggs on the pest’s larvae and when they hatch, they kill it.”

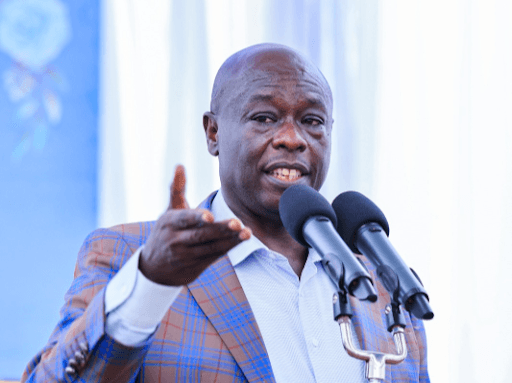

Dr Kasina Muo, a researcher at the Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organisation (KALRO) at a maize farm infested with the fall armyworm /AGATHA NGOTHO

Dr Kasina Muo, a researcher at the Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organisation (KALRO) at a maize farm infested with the fall armyworm /AGATHA NGOTHOKalro is also developing digital tools to help farmers monitor and manage pest populations.

“We want to give farmers something like an app that uses weather and climate data to forecast pest outbreaks. This will help them make informed decisions on when and how to apply pest control measures,” Muo said.

Kennedy Senagi, a data scientist at the International Centre for Insect Physiology and Ecology (Icipe), is part of the team using artificial intelligence to predict pest movements and outbreaks.

“We collect data from satellites, sensors and farmers to build models that predict where pests like the fall armyworm are likely to spread,” he said.

“This allows the government and other stakeholders to act early and provide interventions before the pest spreads to new regions.”

The goal is to make such information easily accessible.

“Eventually, farmers should be able to go online or use their phones to get timely information on pest risks in their areas,” he said.

In Mwala subcounty, agricultural extension officers have been key in linking farmers to research and training.

Muthwii Mutisya, an extension officer in Masii ward, said their goal is to ensure farmers get food and income.

“We have faced challenges from emerging pests, but through partnerships with Kalro, we’ve found better ways to manage them,” he said.

They are encouraging farmers to adopt the IPM approach and avoid depending solely on agrochemical shops for advice.

“We train farmers in groups and through demonstrations. So far, we’ve reached more than 7,000 farmers,” Mutisya said.

Dr Zachary Kinyu, who coordinates crop health research at Kalro said maize is more than just food, it is a symbol of stability, and protecting maize means safeguarding national food security.

“When you mention maize in Kenya, it’s emotional,” Kinyu said.

“When we have maize, we feel secure. But when pests destroy it, people panic.”

He said the new biological and digital technologies will help farmers reduce losses and costs.

“By using parasitoids and other eco-friendly controls, farmers won’t have to spray three or four times,” he said.

“Some may not even need to spray at all.”

Kinyua said the impacts go beyond individual farms.

“If we reduce maize losses by 30 to 70 per cent, we increase national production and food availability. In addition, when farmers have enough to eat and to sell, the whole country benefits,” he said.