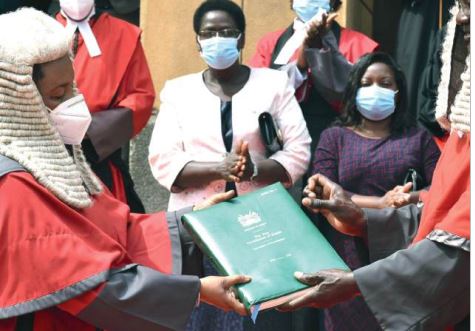

Then acting Chief Justice Philomena Mwilu receives a copy of the constitution on January 12, 2021 /FILE

Then acting Chief Justice Philomena Mwilu receives a copy of the constitution on January 12, 2021 /FILE

A treaty (an agreement between Kenya and one or more other countries or an international organisation) can be more directly relevant to Kenyans than how ambassadors are appointed.

Article 2(6) of the Constitution says, “Any treaty or convention ratified by Kenya shall form part of the law of Kenya under this Constitution.” This had not appeared in any draft of the constitution.

Under the old constitution, entering into a treaty was solely the responsibility of the Executive (“government”). Parliament had no role. However, it was customary to notify Parliament, before the final steps of ratification which would make the treaty binding on the country, in case they wished to debate it. (I owe this information to the interesting LLM dissertation of former Chief Juistce David Maraga).

The way a treaty got into Kenyan national law, if necessary, was by Parliament passing legislation (it was called “domesticating” the treaty). From Article 2(6) you would think that is no longer necessary. It gives an impression that Kenya is becoming like some other countries - mostly ones that follow law deriving from continental European systems – that consider national and international law as one system, so a treaty becomes part of their national law.

Soon after, the Treaty-Making and Ratification Act, 2012 was passed to involve Parliament in approving treaties for ratification – if a treaty was to become law automatically it should have the approval of the people’s representatives.

How does it work?

The 2012 Act allows the Executive to negotiate treaties, setting out a few common sense things that should be thought about. The Cabinet must approve at an early stage. After the treaty is signed it again goes to Cabinet: and the question is should it be ratified? Getting to this stage may take some time. It may never happen.

If Cabinet wants it ratified it goes to Parliament – actually the National Assembly not the Senate, even if counties would be affected. Why not? Senate would be involved if domesticating legislation concerned counties. The Act was passed before Senate existed.

The Cabinet Secretary sends the treaty with a brief explanatory note to the National Assembly, which sends it to a committee. If Parliament approves, the treaty is ratified – a formal process involving the relevant CS signing a document.

Let’s unpick the whole process.

Effect of Article 2(6)

Some people were quite excited about the change. Many imagined this would be good for human rights – because human rights treaties would automatically become part of Kenyan law. Also perhaps environmental treaties. Some people would have been thinking about treaties that affect the economy – like double taxation agreements.

Kenya was already a party to many human rights treaties, and the constitution itself has very full human rights provisions, some inspired by those treaties. It’s not surprising that recent treaties have generally not been human rights treaties.

During the current Parliament 23 treaties (they may be called something else like agreement) have been presented to Parliament for approval.

Four related to environmental issues; two to health issues; two to tax, five broadly to economy questions, one to migrants to Germany, one to cultural property, one to defence, two to aviation, and one to a possible African Union Parliament.

Sixteen were approved; four are still being considered; three were rejected.

The Act exempts certain types of treaty from the requirement of Parliamentary approval: if they are “necessary for matters relating to government business” or relate to “technical, administrative or executive matters”.

This vague language has been criticised as making it too easy to exclude a treaty from Parliament’s oversight.

In an unsatisfactory case in 2019 the court allowed the government to get away with not asking for Parliament’s approval of a double taxation agreement with Mauritius – although such treaties may have serious effects on a country’s economy. However, recently such an agreement with Singapore was sent to Parliament.

The Supreme Court arguably limited the scope of Article 2(6) in the Mitubel case – in some ways a good case on housing rights. The court held that Article 2(6) means that international law is part of Kenyan law unless it goes against “the Constitution, local statutes, or a final judicial pronouncement.” This will make the idea of treaties being automatically part of Kenya’s law much less important.

The court seems to have ignored the fact that the Article 2(6) says treaties become law “under this Constitution” (never even quoting the phrase). Clearly treaties cannot contradict the Constitution – but Article 2(6) seems to give international treaties a status below the constitution but not below other law.

The court justified its decision partly on the basis of a quote from a 1764 English case (a statement that no longer reflects English law) and a misunderstanding of the American law on treaties.

Article 2(6) means rather less than readers thought it meant in 2010.

Participation

Under the Act the parliamentary committee must

ensure public participation in deciding whether to approve ratification of a

treaty. On October eighth Parliament asked for public input on a treaty to

amend Article 24(2) of the Protocol on the Establishment of the East African

Community Customs Union – by October 20.

As with Bills the time given is short. Bills get more publicity, and a

good number of people will understand the issues. It is perhaps not surprising

that generally there seems to be very little input on treaties. More needs to

be done to “ensure” participation.

The ratification stage seems rather late for the involvement of Parliament and the people. Interestingly an amendment Bill at an advanced stage in Parliament would require the CS to inform the National Assembly within two weeks of beginning negotiations on a possible treaty. This would also give the public more advance notice of something they might want to comment on later.

Parliament’s role

Mostly relevant National Assembly committees do the work. They meet the relevant CS, consider any submissions (mostly from government agencies rather than the public) and usually recommend approval.

One has a sense that, as usual, Parliament does what government wants.

Rather different was a recent National Assembly debate on three conventions intended to protect children and parental rights where parents were separated and in different jurisdictions, sometimes one parent even having abducted children against the other parent’s wishes.

The committee recommended approval. Many MPs in the debate did, too. But a male dominated wave of MPs, seems to have convinced a majority to reject the convention as “contrary to our customs, laws, ethos and everything that is not African” as one, said. Many did not seem to know clearly what the conventions would do, but seemed influenced by fears of Kenyan men being required to support their children in another jurisdiction, resenting the contribution of women MPs in support of the conventions, even in one case imagining that children would be compelled in western countries to undergo sex change operations (It’s Hansard April 17 (pm) 2023, if you are interested).

Clearly more education of MPs and public is needed.

Unratified treaties

Kenya has signed but never ratified at least 11 treaties. The original Ratification Bill required government to publish Bills to implement all treaties signed before the new constitution. This was perhaps unrealistic; anyway it does not appear in the final Act.

This leaves some uncertainty - does Kenya plan to be bound by these treaties or not? Should we not have some process for making decisions about them? Last month AA Kenya was calling on government to ratify the African Union Road Safety Charter, 2016; it needs three countries to ratify for it to come into force.

Another signed but not ratified treaty is the one on enforced disappearances, signed by Kenya in 2007. It seems unlikely this government would seek to ratify it.