The United Nations Security Council agreed to transition the Kenya-led Multinational Security Support mission in Haiti into a much more lethal and beefed-up force.

This will be supported by both a newly created

U.N. Support Office and the Organization of American States.

The newly authorized Gang Suppression Force was

approved for a period of 12 months in a vote of 12 in favor, with three

abstentions on Tuesday.

Russia and China, which hold veto power,

abstained.

Kenyan police arrived in Haiti in June 2024.

To Kenya, the move was a relief as the police

there were operating under difficult circumstances.

Like the MSS, the new force will still have a force commander in charge.

But now, it will be overseen by a group of countries

representing the coalition of the willing, troop-contributing countries.

How often will they meet, how will they settle differences,

is one of the glaring issues with the proposal, say experts on peacekeeping

missions, when you consider that soldiers and police who’ve never trained or

worked together are being asked to fight together without clear support.

Also, the new force will be reporting up through

a special representative, a civilian who will provide oversight and political

direction.

The new Gang Suppression Force, or GSF, will

have a ceiling of 5,550 individuals- 5,500 uniformed personnel, comprised of

both military and police personnel, and 50 civilians.

It will still rely on voluntary contributions to fund its personnel; however, its operations and logistics, including the current U.S.-constructed base in Port-au-Prince, will be overseen by the new U.N. Support Office.

In the resolution, the U.N. is asked to provide technical support to the Organization of American States, which is also tasked with assisting both the GSF and Haiti National Police in the form of provisions of food and water, fuel, transport, tents, defense stores, and appropriate communication equipment.

The resolution also makes specific reference to the Haitian armed forces, a sign of the increasingly important role they must play in the fight.

The newly named special representative will also be responsible for coordinating with the U.N. and the OAS on the deployment of such a package to ensure it strengthens joint operations between the GSF and the Haitian police, including through the construction of operational facilities and security infrastructure supporting joint planning and oversight of operations by both forces.

What remains unclear is the cost of the new mission and where the funding for the logistics will come from.

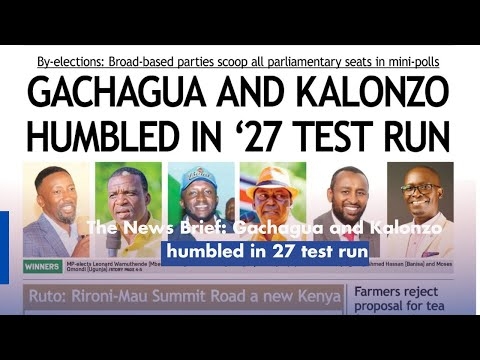

President William Ruto last week said the mission had “achieved” in Haiti, and acknowledged that its lack of equipment, personnel, and resources hampered its ability to take control of gangs. U.S. officials argued that a new, scaled-up, and more lethal effort was needed.

Also, the new mission needed to be able to work

independently of the Haitian police, something the MSS’ mandate did not allow,

which meant that security forces struggled to reduce gangs’ territorial

controls as gunmen coordinated and simultaneously launched attacks in different

corners of the country.

Among the changes that were pushed was stronger

language to ensure children and women are safe, by stressing their recruitment

and rape by gangs, and for Haiti to do more to address the root causes of

instability and carry out reforms in its governance system.

The push was made by Denmark

The goal of the new suppression force is to

support the Haitian police and the Haitian armed forces, and national

institutions to ensure security conditions are conducive to holding free and

fair elections, and that humanitarian aid can be accessed safely and in a

timely manner.

How the two would vote was the biggest

uncertainty going into Tuesday’s meeting, with discussions circulating that

Beijing and Russia would try to prolong the expiring mandate of the Kenyan

mission by a few months but face a veto from the U.S.

Ahead of the vote, the representatives of more

than four dozen countries gathered at a media stakeout to show support for

both the Gang Suppression Force and the U.N. Support Office.

“The unity and collaboration demonstrated by

member states, including the Standing Group of Partners for Haiti and the

United Nations, underscore our shared objective: Put an end to the violence and

suffering so that Haiti may restore security, rebuild strong institutions and

lay the foundations for sustainable development,” Panama’s representative to

the U.N. Eloy Alfaro de Alba read in English and Spanish.

“Any further delay of action by the Security Council could mean continued suffering of the Haitian people, with potential consequences for the stability of the region. We urge all council members to act now and pass the resolution before them so that Haiti may have a chance at a better future.”

Both Russia and China, during negotiations, which were ramped up last week by Washington, had expressed concerns about the new force’s financing, chain of command, and other technical and political questions like the future role of Kenya’s police forces in the new makeup.

Many of those questions persisted, but last week during an address to the U.N. General Assembly, the head of Haiti’s Transitional Presidential Council, Laurent Saint-Cyr, pleaded with the international community for help against the merciless violence.

Haiti has not held elections since 2016, and last had an elected president in 2021 when its head of state, Jovenel Moïse, was assassinated in July 2021 inside his bedroom.

The Haitian state, Saint-Cyr said, wants

elections, but restoring security remains its greatest challenge.

U.N. Secretary General António Guterres, who first proposed in February that the Kenya-led mission be transitioned into a more scaled-up force with a robust mandate, with members’ dues to the U.N. peacekeeping budget used to finance a U.N. Support Office to provide logistical and operational support.

Already this year, more than 3,000 Haitians have died in gang-fueled violence that is also triggering the rise of so-called citizen self-defense groups and the deaths of civilians, including children, in operations using weaponized drones.