This movement aims to transform the lives of thousands of school-going girls.

Despite the presence of NGOs working to empower girls, access to menstrual hygiene products remains a barrier for many in Narok’s remote areas.

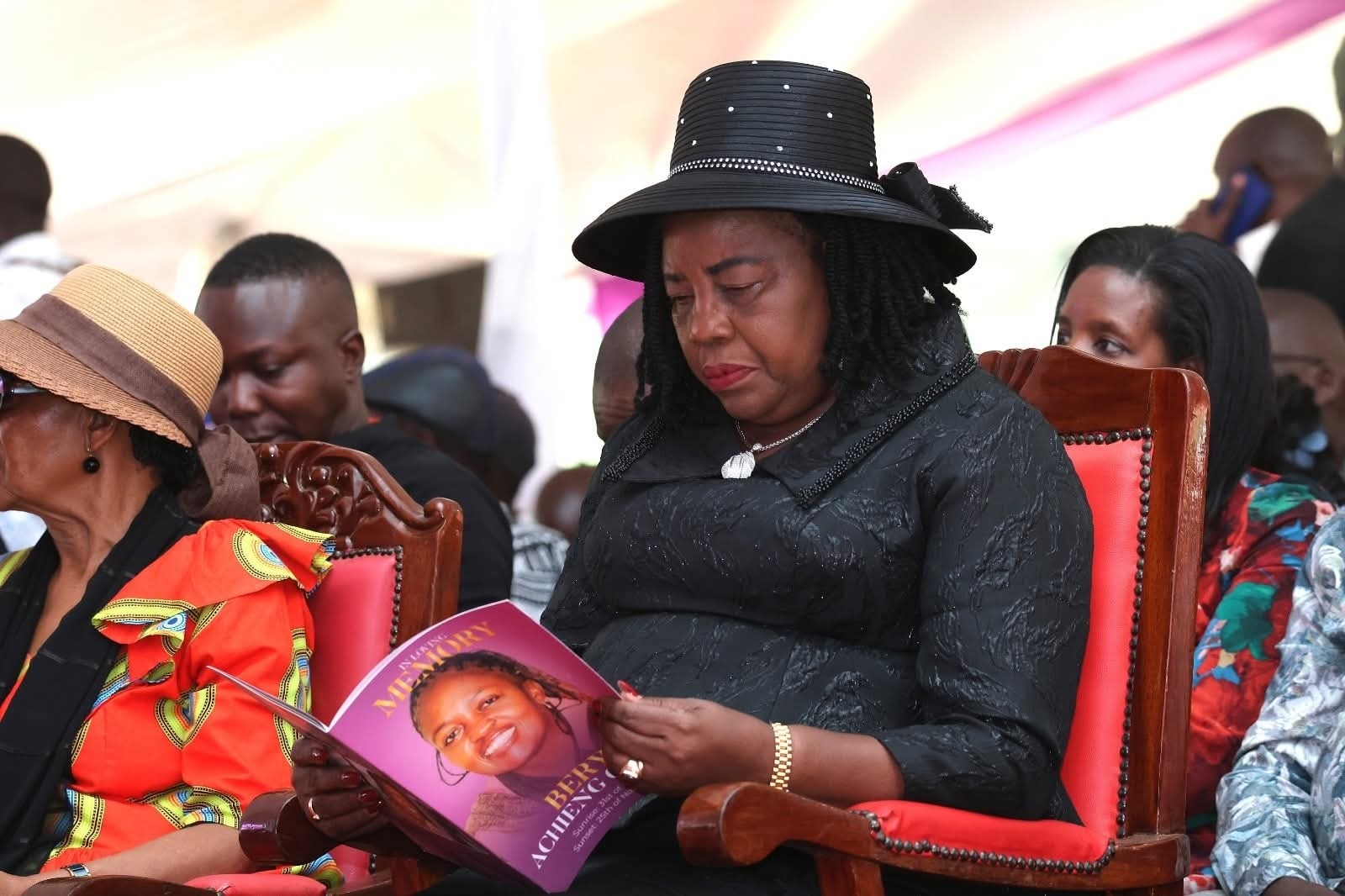

“Menstruation should not be a reason a girl cannot achieve her dreams,” Agnes Ntutu, wife of Narok Governor Patrick Ntutu said.

"Many girls miss class every month. That is 65 per cent in rural areas, missing classes due to a lack of sanitary pads. This has led to stigma, absenteeism and in some cases, dropping out of school entirely.”

Ntutu made the remarks at Maji Moto in Narok South during this year’s World Menstrual Hygiene Day.

In her address, she called on parents, local leaders, government agencies and development partners to make menstrual health a collective priority.

For girls like 17-year-old Naisula (not her real name), a Form Three student in a day school near Ololulunga, periods are more than just a biological occurrence; they are a source of monthly anxiety.

“There are days I’ve had to stay at home because I didn’t have pads,” she shared.

“Sometimes I use cloth or paper, but it’s uncomfortable and I’m always worried about leaking.”

Stories like Naisula’s are all too common in Narok.

In many pastoralist communities, cultural taboos have created an environment where even mothers feel embarrassed to discuss menstruation with their daughters.

As a result, girls are left unprepared, misinformed and unsupported.

NGOs have played an invaluable role in bridging this gap.

“Your support has restored dignity, confidence and hope to our young girls,” she said, commending organisations that have distributed menstrual products and conducted awareness campaigns in hard-to-reach areas.

Many of these non-governmental organisations have been running menstrual hygiene workshops and providing reusable sanitary kits in schools across the county.

Their programmes extend beyond just providing pads; they focus on empowerment. They educate girls about their bodies, hygiene and self-worth and engage with boys and male teachers to break down stigma.

However, the need remains urgent. A recent survey by an NGO focusing on education indicated that menstrual-related absenteeism is one of the top five factors affecting girls' education in Narok’s rural zones.

The lack of sanitation facilities in schools, long distances to shops and high poverty levels all exacerbate the challenge.

Ntutu urged county and national government actors to prioritise menstrual health as a policy issue.

“We cannot talk about empowering the girl child without addressing this very basic need. If we want our girls to excel, they need to be in school every day of the month,” she said.

Her call to action also included a plea to parents: “Let us not wait for donors or NGOs. As parents, it is our duty to make sure our daughters are safe, confident and supported through every stage of their lives.”

As the event concluded, schoolgirls received menstrual kits donated by local partners, their smiles revealing the relief of knowing someone cared.

In a county often labelled as marginalised and remote, moments like these signal hope. The journey towards menstrual dignity in Narok may be long, but for girls like Naisula, each day with dignity and confidence is a step closer to a brighter future.