The small village of Mwanga in Taita Taveta County was rocked by horror on the morning of November 28, 2018, when the body of Mwangesha Mwamburi, an elderly villager, was discovered lifeless in his own home.

His son, Boniface Mwakio Nyali, now convicted of murder, stood accused of inflicting the fatal injuries that led to the elderly man’s death.

What initially seemed like a medical emergency turned into a grisly crime scene, unraveling through eyewitness accounts, chilling testimonies and a web of circumstantial evidence.

A suspicious confession

The incident began on the evening of November 27, 2018, when Patrick Maghanga, a local farmer, visited Nyali’s home.

According to Maghanga, he found Nyali outside his house with another villager named Mshimba. It was during their conversation that Nyali made a disturbing claim.

“He was explaining to Mshimba that his deceased father approached him in his room the previous night with the intention of making love to him,” Maghanga testified in court.

“Agitated by the alleged move, Nyali fought the deceased and twisted his neck.”

Maghanga said he never saw the deceased that day, only hearing from Nyali that his father was injured inside the house and would die within seven days.

Despite the harrowing statement, Maghanga and Nyali proceeded to harvest coconut juice together, parting ways that evening as if nothing had happened.

The next day, Maghanga received a phone call informing him that Mwamburi had been found dead.

The door was locked from outside

Nancy Maura Mwakio, the chairperson of Nyumba Kumi in the village, also had a chilling encounter with Nyali.

On November 28, he appeared at her shop around 6 pm, unusually early from his usual work in Voi, prompting her to ask why he was back so soon.

“Nyali told me that Mwamburi had tried to rape him the previous night and, as a result, he beat him and pushed him against the wall,” she told the court.

Concerned, she called Beatrice Nguvu to check on the situation, but it was not until the next day that action was taken.

Nguvu, along with relatives and others, made their way to Mwamburi’s home. The house was locked.

“We pushed the door until we gained access,” Nguvu recounted. Inside, they found the elderly man dead on his bed.

The relatives told the court that Nyali admitted to killing his father.

They immediately informed the village elder, the area chief and the assistant chief, who called Mwatate Police Station.

A troubled past, a violent end

Witnesses painted a picture of tension and volatility.

According to Nguvu, Nyali was “a troublesome person who had problems with his wife” and once threatened to kill her.

Mwamburi, on the other hand, lived alone before Nyali moved in with him about six months earlier.

Police photographs showed the body had been wrapped in a mattress. The officers said Mwamburi had sustained injuries on the left hand, neck and back.

There were no signs of forced entry into the house. Mwamburi’s injuries told a story of unimaginable brutality.

They arrested Nyali at the scene.

A catalogue of violence

Moi Voi Referral Hospital’s Dr Joynar Weni, testifying on behalf of the pathologist who conducted the autopsy, listed the injuries: multiple stab wounds on the face, fractures on both sides of the ribs, bruises on the elbows, skull fractures and bleeding inside the brain.

Both lungs had been perforated. There was a haemothorax—around a litre of blood in the chest cavity.

The cause of death was clear: severe head and chest injuries due to blunt force trauma.

“The conclusion thereof was that the cause of death was severe head and chest injuries secondary to blunt force trauma,” the court heard.

The defence: A dying man, not a murder

When the trial began, Nyali denied that he had killed his father, and that he had confessed to it.

He claimed he only told Mwakio and others that his father had a “throat problem.” He said he had called Nguvu’s husband, and that together they found Mwamburi groaning in pain.

He said he administered painkillers, but the old man could not swallow.

Eventually, his father died after vomiting, he claimed.

In cross-examination, he introduced a different account: that his father had fallen from bed twice and choked himself.

Nyali denied having knowledge of the origin of the injuries on the deceased’s body

A chain of circumstantial evidence

The trial judge dismissed the shifting defence, describing it as “a mere denial.”

With no signs of forced entry, and with Nyali living alone with his father in a locked house, the court concluded that only he could have inflicted the injuries.

The testimonies of Maghanga and Mwakio were especially damning, as both reported Nyali confessing to assaulting the deceased the night before his death.

The court found these statements credible and linked them directly to the injuries recorded in the post-mortem.

“The appellant’s (Nyali) disclosure to his friend, Mshimba and Mwakio that he had fought with the deceased, coupled with the nature of injuries sustained by the deceased, all called for the reasonable inference that the only person who had the opportunity to attack the deceased was the appellant himself; and that the unbroken chain of events irresistibly pointed a blameworthy finger towards the appellant,” the trial judge said.

“The parts of the body that were targeted—chest, head, and neck—are all delicate... the intention was either to cause grievous bodily harm or kill the deceased.”

Malice aforethought

The severity and location of the injuries—multiple skull fractures, lung perforations and rib fractures—pointed to a deliberate and violent assault.

The High Court concluded that Nyali acted with “malice aforethought,” a key element in a murder conviction under the law.

As such, he was found guilty and sentenced to 20 years in prison.

Appeal dismissed

Nyali later appealed the verdict, claiming the conviction relied too heavily on circumstantial and hearsay evidence.

His lawyer argued there was no eyewitness to the murder and no conclusive proof that Nyali was the last person seen with the deceased.

The lawyer argued that there were no known reports of assault, mischief, mental or physiological mistreatment from Nyali to the authorities, nor did the neighbours testify to ever hearing calls of distress from the deceased’s household.

But the Court of Appeal upheld the conviction, ruling that the circumstantial evidence was overwhelming and consistent.

The “last seen” doctrine, they said, applied squarely: the person last seen with the victim before their unexplained death bears responsibility.

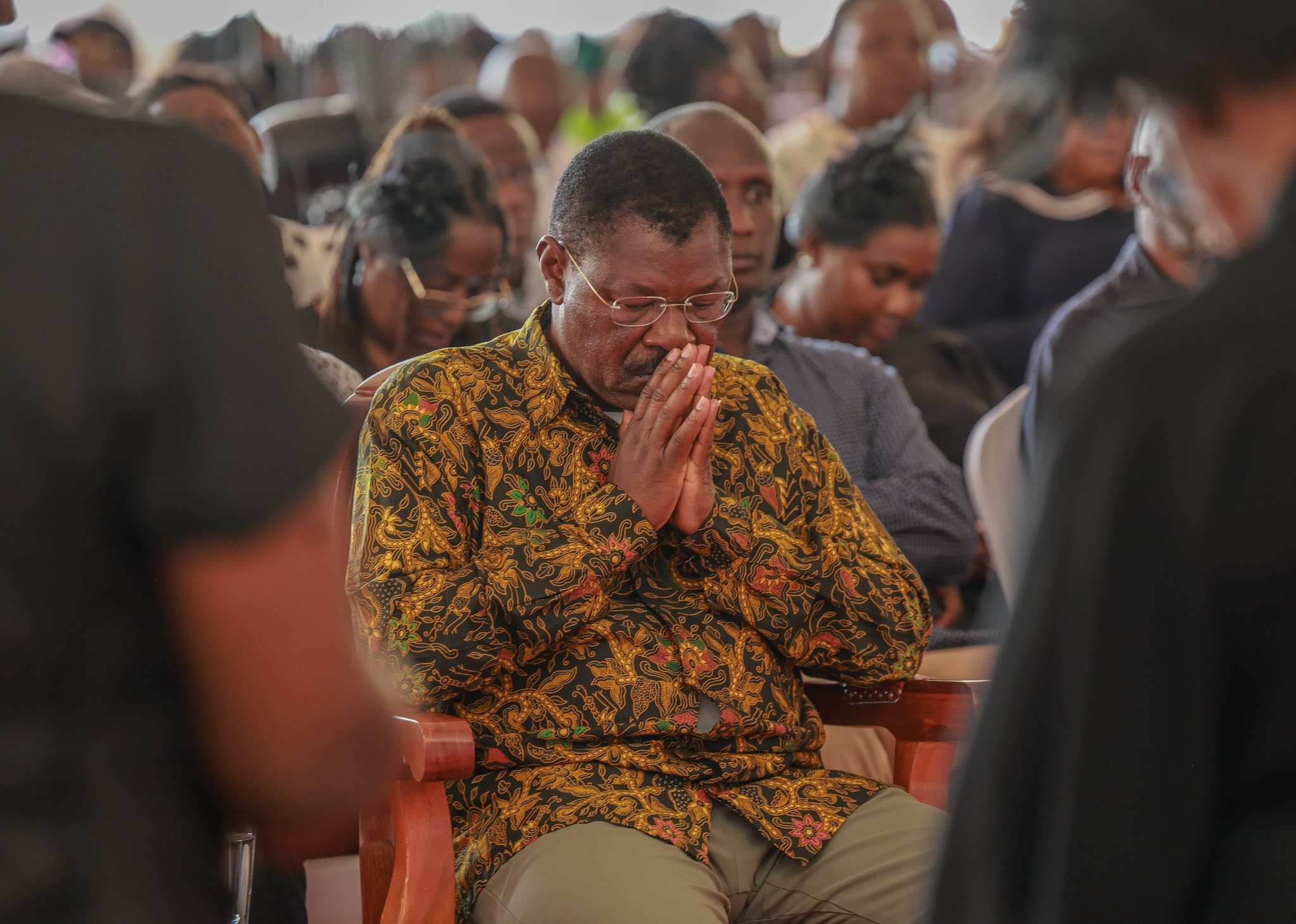

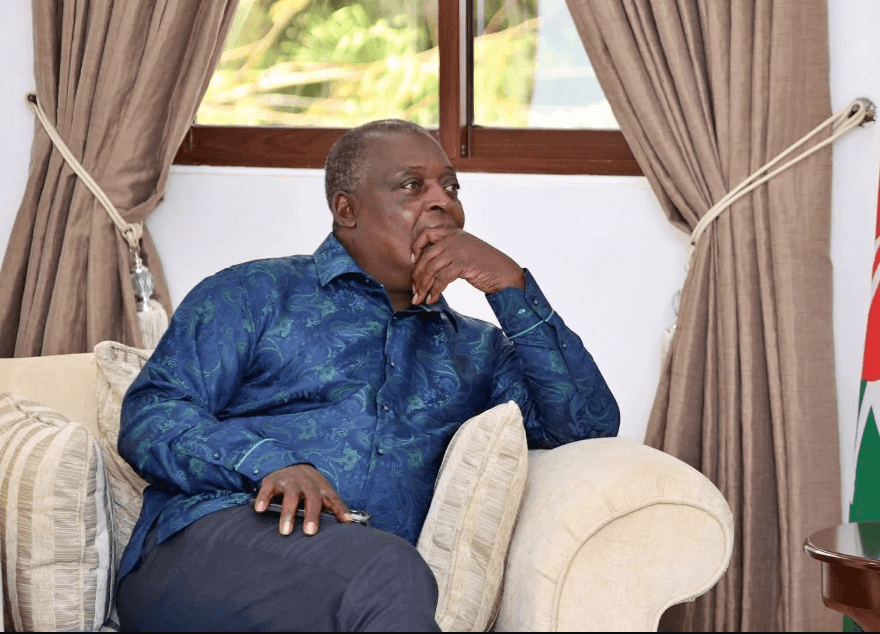

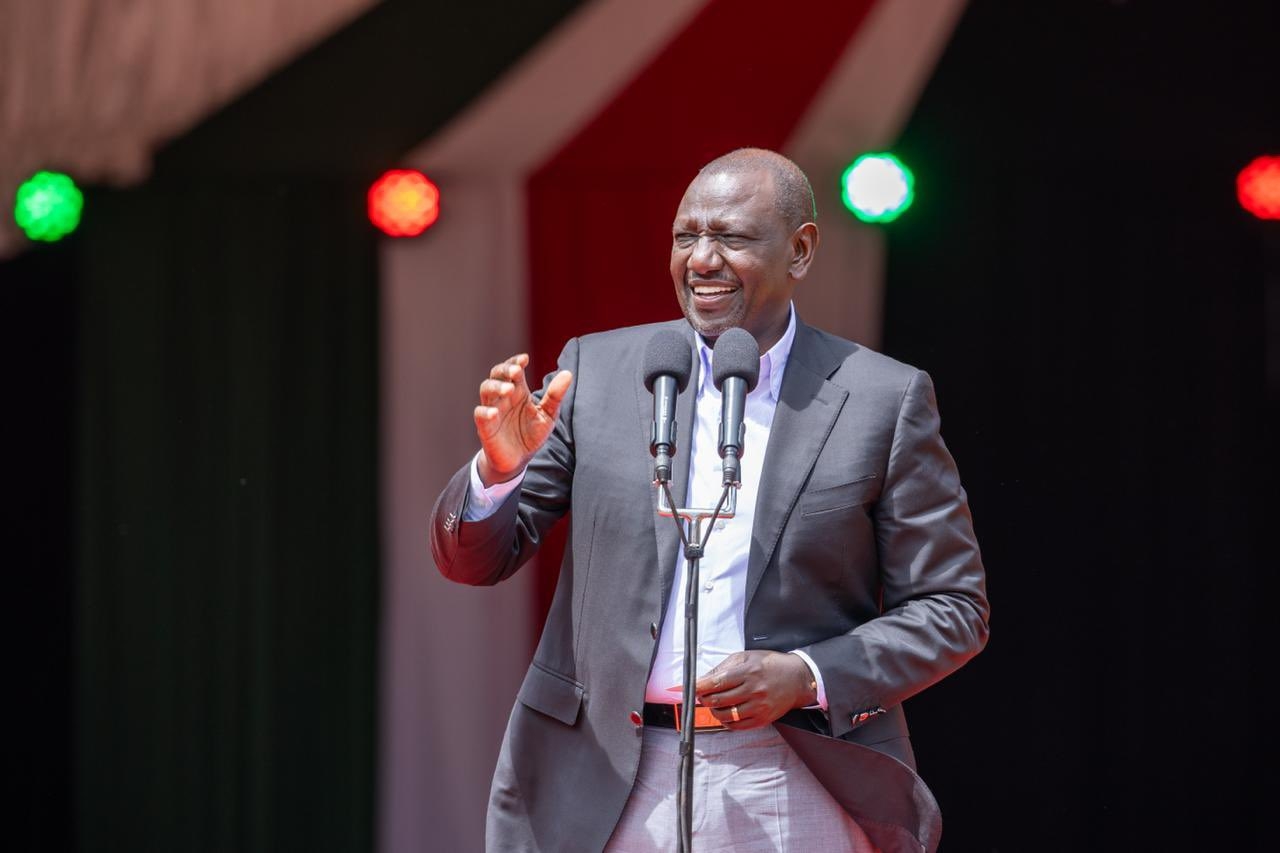

The appellate judges— Kibaya Imaana Laibuta, F. Ochieng, and Ngenye-Macharia - noted that Nyali failed to provide a credible explanation for the injuries.

They noted that his contradictory versions only deepened suspicion.

The court emphasised that the burden of proof remained on the prosecution, and in this case, it was met “beyond reasonable doubt.”

“In view of the foregoing, we find that the prosecution proved its case beyond reasonable doubt. We hereby uphold the judgment of the High Court at Mombasa delivered on July 14, 2023. We find the appeal to be without merit and hereby dismiss it in its entirety,” the judges ordered.