Kenya's inflation crisis has shifted from just a news story to an

urgent reality for families nationwide.

The recent Consumer Price Index reveals a stark truth: many

households are forced to make heart-wrenching decisions. They are forced to choose between

paying rent or buying groceries, covering school fees, or repaying loans.

The Consumer Price Index (CPI), as defined by the Kenya National

Bureau of Statistics, serves as an essential macroeconomic indicator used to

monitor price fluctuations and their implications for policy decision-making.

It is quantified as the weighted average change in retail prices

consumers incur for a designated basket of goods and services.

This critical indicator, compiled monthly by the Kenya National

Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) across 50 urban zones, reveals a detailed narrative

about the cost of living.

The March 2025 data shows annual inflation accelerating to 3.5 per cent up from 3.3 per cent in February, meaning Kenyan families now need 3.5 per cent more to

maintain the same standard of living.

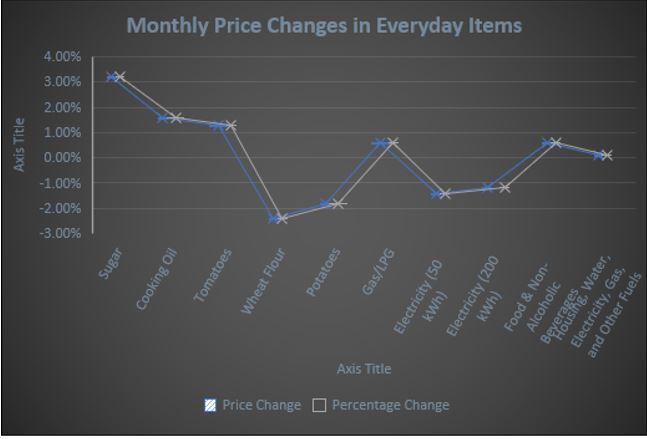

This creeping inflation is most evident in supermarket aisles, where the Food and Non-Alcoholic Beverages Index rose 0.6% in just one month.

Staple items like sugar (+3.2 per cent), cooking oil (+1.6 per cent), and tomatoes

(+1.3 per cent) have become noticeably more expensive, although small reprieves were

provided by slight declines in wheat flour (-2.4 per cent) and potatoes (-1.8 per cent).

The housing sector tells a similar story of financial strain, with

the Housing, Water, Electricity, Gas and Other Fuels Index inching up 0.1 per cent,

propelled by a 0.6 per cent surge in gas/LPG prices that hit hardest at the kitchen

stove, even as electricity costs saw modest relief with 50 kWh and 200 kWh

prices dropping 1.4 per cent and 1.2 per cent respectively.

Behind these statistics are real families making painful budget

decisions. Jane Wanjiru, a mother of three in Nairobi's Jericho, watches

helplessly as her grocery bill balloons from Sh500 to Sh800 for the same basic

items.

Wanjiru, a hairdresser at Uhuru Market, discusses the challenges

she faces in balancing her business and personal finances.

“You see, once fuel prices go up, everything just goes haywire,”

she says while eyeing the tomatoes at Wakulima Market.

“Matatu fare shoots up, milk delivery becomes expensive, and the

shopkeeper adds their own on top to recover transport costs. In the end, it’s

us who suffer. You’re forced to choose between buying unga or paying school

fees—it’s crazy!”

The situation worsens in informal settlements. I speak with

twenty-nine-year-old Monica Tata, a resident of Kawangware.

Tata describes some of her struggles as a mother of two and a

house manager in Lavington, earning KES 15,000 monthly. She describes skipping

meals to feed her children and sometimes being unable to afford her daughter's

school fees.

“A few years ago, we could get by on my little salary since things

were not as expensive,” she recounts.

“My daughter attends a public school only because it’s what we can

afford. It breaks my heart because my daughter is so bright, and she deserves

more.”

Moreover, Tata said her family could no longer afford any food

beyond githeri due to rising living costs.

“The economy is unbearable. I can’t remember the last time my

family ate anything aside from githeri,” Tata said.

“I have to save for my children to at least go to school. My

daughter’s school keeps sending notes about unpaid fees, and I am completely

stretched.”

Macro-finance specialist Hassan Manyara frames this as more than

an economic challenge but a full-blown social crisis with generational

consequences.

"When parents must choose between feeding their children and

paying school fees, when workers lose motivation because their salaries buy

less each month, we're not just talking about inflation percentages—we're

watching Kenya's human capital erode in real time," he warns.

Manyara points to Kenya's shrinking disposable incomes, which are

creating a vicious cycle of reduced consumer spending that further weakens

businesses, leading to job cuts and further spending reductions.

“Despite constitutional guarantees, consumer protection in Kenya

remains almost non-existent. Article 46 of the Constitution ensures the right

to safe, reasonably priced, and accurately labelled goods and services."

He finishes by saying governmental agencies such as the

Competition Authority and the Kenya Bureau of Standards, which are tasked with

enforcement and supported by the Consumer Protection Act (2012)—are not doing

enough to ensure consumer protection and standards are realised.

Manyara offers a solution by proposing comprehensive tax reforms

aligned with Adam Smith's principles, shifting the burdens to high-impact

sectors like manufacturing and commercial agriculture, while eliminating

nuisance taxes that strangle small traders.

"Our tax policies should stimulate growth, not just extract

revenue from struggling citizens," he argues, noting that neighbouring

Tanzania has managed to keep food inflation below 2 per cent through targeted agricultural

investments.

Nyandemo says Rwanda and Ethiopia compellingly model their

approach through the streamlining of business taxes and the slashing of

nuisance taxes on small traders, while offering incentives for agro-processing

and manufacturing.

“Rwanda cut corporate rates applicable for priority sectors to

15 per cent, and Ethiopia exempted farm inputs of all types from VAT, which led to some

meaningful growth for both without fueling any inflation, which the World Bank

attributed,” he said.

Nyandemo argues that Smith’s principles of efficiency, equity, and

economic stimulus can work well in practice.

“Kenya’s fixation with taxing survivalist enterprises only deepens

the existing poverty, while Rwanda's success could easily be replicated through

smarter fiscal policies: much more investment into sectors that really drive

prosperity, relatively fewer burdens upon the vulnerable,” he said.

Auditor and financial analyst Gladwell Maingi advocates for a

multi-pronged approach, including strategic subsidies for staple foods modelled

after Rwanda's.

Maingi also describes Rwanda’s strategic subsidy model, aligned

with its Economic Development and Poverty Reduction Strategy (EDPRS), which

targets key sectors like agriculture (e.g., e-voucher fertilisers) and energy

(e.g., subsidised solar) to boost productivity and inclusion.

She attributes its success to precision targeting, rigorous

accountability, and political goodwill.

Maingi particularly criticises government waste that undermines

development, citing the 2024 Auditor General's report revealing Sh18 billion

spent on dubious contracts and unpaid bills while the public wage bill balloons

with politically motivated hires.

Moreover, Maingi noted how worrying it was that the Treasury

couldn't account for over KES 7 billion in government assets.

“They don’t even have a complete asset register—that’s basic

accounting. If this were a business, it would be a scandal.”

Maingi also criticises the Telkom shares transaction that was

never approved by Parliament.

“We’re seeing billions allocated without proper documentation. The

Auditor General flagged Sh6.2 billion spent on Telkom shares that was never

approved by Parliament. That’s not just poor oversight; it’s fiscal

indiscipline at the highest level.”

According to Maingi, foreign investors have taken notice of these

dysfunctions, with the Nairobi Securities Exchange reporting a 40% drop in

foreign portfolio inflows compared to 2023.

"Investors see the unmanaged inflation, the corruption

scandals, and the policy inconsistencies, and they're voting with their

feet," says Maingi.

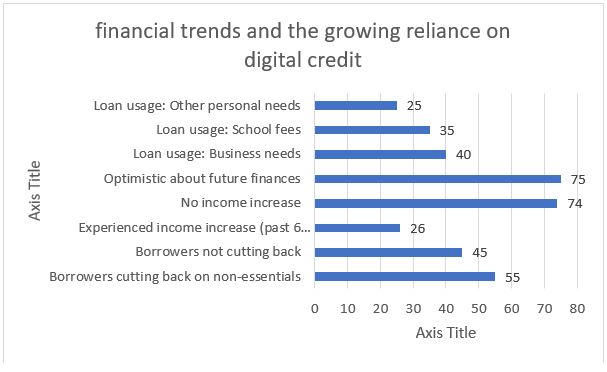

Meanwhile, fintech and microfinance expert Melanie Ambasa breaks

down the Digital Financial Services Association of Kenya (DFSAK) report, in

which Tala highlights key financial pressures faced by Kenyans, exacerbated by

inflation.

"What we're seeing is a fundamental shift—digital loans are

no longer just for emergencies; they've become a regular part of how families

bridge the gap between paychecks."

Ambasa explains that data from the 2024 DFSAK and Tala reports

show that over half of borrowers—fifty-five percent—are cutting back on

essentials like food and transport to repay loans.

“Despite seventy-five percent expressing optimism about the

future, only 26% saw income growth in the last six months. Most loans are used

for business expenses, school fees, and personal needs,” Ambasa said.

Ambasa noted that the growing reliance on digital credit presents

both opportunities and risks.

On one hand, she says, mobile loans provide quick access to funds

for school fees or business needs, but she also warns of a potential debt trap.

"The convenience of digital lending comes with real

dangers," cautions Ambasa.

"When used responsibly, these tools can help weather

financial storms, but without proper safeguards, they can deepen financial

stress."

The report highlights particular challenges for microfinance

institutions, as demand for loans increases, which in turn increases default

risks.

"We're walking a tightrope—we want to serve our customers,

but we also have to maintain responsible lending practices," Ambasa said.

Moreover, Ambasa emphasises the urgent need for financial

education.

"Literacy programs aren't just nice to have anymore—they're

essential armor in this economic climate."

While the government has implemented stopgap measures, such as

fuel subsidies and tax breaks for farmers, experts like Ambasa agree that these

measures are simply not enough.

As Jane Wanjiru, the mother of three we spoke to, puts it,

"Inflation isn't just numbers in the news; our investment dreams are being

crushed as we’re living cheque to cheque. God, just help us."

“Without urgent, coordinated action addressing both the economic

and governance dimensions of this crisis, we will continue to see the rise of

diminishing opportunities and growing desperation among many Kenyans,” Ambasa

said.

The project received support from the Thomson

Reuters Foundation as part of its global work aiming to strengthen free, fair

and informed societies. Any financial assistance or support provided to the

journalist has no editorial influence. The content of this article belongs

solely to the author and is not endorsed by or associated with the Thomson

Reuters Foundation, Thomson Reuters, Reuters, nor any other affiliates.