They creep in silently.

Diabetes, hypertension, cancer, and stroke are emerging only when the damage

is already done.

For many families, the first sign is not a symptom but a sudden hospital

bill that drains savings, or a funeral that leaves children without a parent.

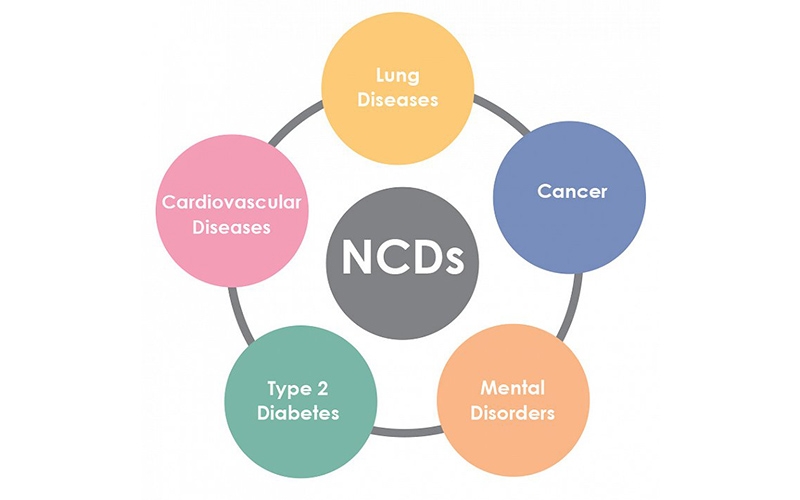

According to the World Health Organization, 18 million people die from

non-communicable diseases (NCDs) before age 70, with 82% of these deaths

occurring in low- and middle-income countries, and Kenya is no exception.

Yet, in our public discourse, NCDs rarely receive the same attention or

funding as infectious diseases like COVID-19, HIV, malaria, or tuberculosis.

Beyond the human toll, the economic burden is immense.

Dialysis for kidney failure costs around Sh9,500 per session in private

hospitals, chemotherapy can run into hundreds of thousands of shillings per

cycle, and lifelong medications for diabetes or hypertension quietly chip away

at family incomes.

These costs push households into poverty and divert national resources away

from development, slowing down Kenya’s progress toward the Big Four Agenda and

Vision 2030.

The Universal Health Coverage (UHC)the vision that every Kenyan should

access quality health services without financial ruin cannot be realized if

NCDs remain unchecked.

A health system stretched thin by expensive treatments cannot deliver

equity. Prevention must therefore sit at the heart of the Universal Health Coverage.

Prevention begins with food. In many Kenyan households, the menu has shifted

dramatically.

Fast-food chains have become symbols of modern living, while indigenous

foods sorghum, millet, sweet potatoes, beans, and leafy vegetables, are

sidelined as old-fashioned.

Ironically, these very foods once shielded communities from the NCDs now

crippling families. Nutrition is not just a matter of personal choice but of

national policy.

By subsidizing fruits, vegetables, and legumes while taxing sugary drinks

and ultra-processed snacks, Kenya can make healthier diets the affordable

option for all.

The road to UHC is paved not only with hospital beds but also with kitchen

gardens and school feeding programs.

The challenge is that prevention lacks urgency.

Its success is invisible. No one celebrates the heart attack that never

happened, the cancer that never developed, or the stroke that was quietly

avoided.

Politicians gain little credit from prevention policies, and individuals

often underestimate risks until it is too late.

Still, bold solutions exist. Kenya must reimagine food policy.

Subsidies and incentives should shift from maize meal and processed foods to

healthier alternatives like pulses, fruits, and vegetables.

Just as taxes on tobacco have reduced smoking, levies on sugary drinks and

ultra-processed snacks could curb consumption while raising funds for health

promotion.

Second, urban planning must prioritize physical activity.

Sidewalks, cycling lanes, and green spaces are not luxuries they are public

health infrastructure.

Nairobi’s traffic jams are more than an economic headache; they are a public

health crisis, robbing citizens of time for movement and exposing them to

harmful emissions. A walkable city is a healthier city.

Third, health systems must focus on early detection.

Simple blood pressure checks, blood sugar tests, and cancer screenings can

catch diseases early, saving lives and cutting long-term costs.

Community health workers, who have been instrumental in HIV control, can be

retrained to incorporate NCD prevention and follow-up in their visits.

Equally important is shifting social attitudes. NCDs are often framed as

“diseases of the rich,” yet they are hitting the poor hardest.

In informal settlements, where cheap fried foods are often the only option

and exercise space is limited, obesity, diabetes, and hypertension are rising

rapidly. Public awareness campaigns must therefore be inclusive, practical, and

culturally sensitive.

Digital platforms can help bridge this gap. YouTube, Twitter, and TikTok

spaces are not just entertainment hubs they are powerful tools for health

education.

Imagine a campaign where influencers, doctors, and everyday Kenyans share

affordable diet tips, exercise routines, and survivor stories.

Imagine hashtags that make nutrition aspirational again. In a youthful

country where 75% of the population is under 35, prevention must be rebranded

to resonate with digital natives.

Still, the story of NCDs is not just about medicine or policy. It is about

dignity, opportunity, and equity.

When a father cannot afford insulin, or a mother dies of cervical cancer

because screening was out of reach, a family’s future collapses. Education

suffers. Productivity declines.

Development slows. NCDs are not just a health crisis they are an economic

and social justice issue.

Globally, there are inspiring examples. In Mexico, a tax on sugary drinks

led to reduced consumption and increased awareness.

In Finland, community-driven food programs dramatically lowered heart

disease rates within a generation. Kenya can adapt such models, blending global

evidence with local innovation.

At the individual level, change is also possible. Choosing traditional

Kenyan foods over processed alternatives, carving out time for daily movement,

and supporting smoke-free and alcohol-moderation initiatives are small but

transformative steps.

Communities can revive kitchen gardens, schools can strengthen nutrition

education, and workplaces can integrate wellness into daily routines.

Of course, not every Kenyan has equal access to this reinvention.

Socioeconomic divides shape how NCDs are experienced.

In rural areas, healthcare facilities lack diagnostic equipment. In poor

households, even basic preventive measures like fruits or screenings remain out

of reach.

Closing these gaps is crucial if NCD prevention is to become not just a

slogan but a lived reality.

Ultimately, the story of NCDs must shift from despair to empowerment.

Just as Kenya confronted HIV and polio with awareness, policies, and

innovation, so too can we tackle NCDs with bold, preventive solutions.

It is not only about saving lives but

about unlocking Kenya’s economic potential by protecting its most valuable

resource its people.

Silent killers they may be, but with courage, collaboration, and creativity,

NCDs can be transformed into an opportunity for a healthier, stronger, and more

resilient Kenya.