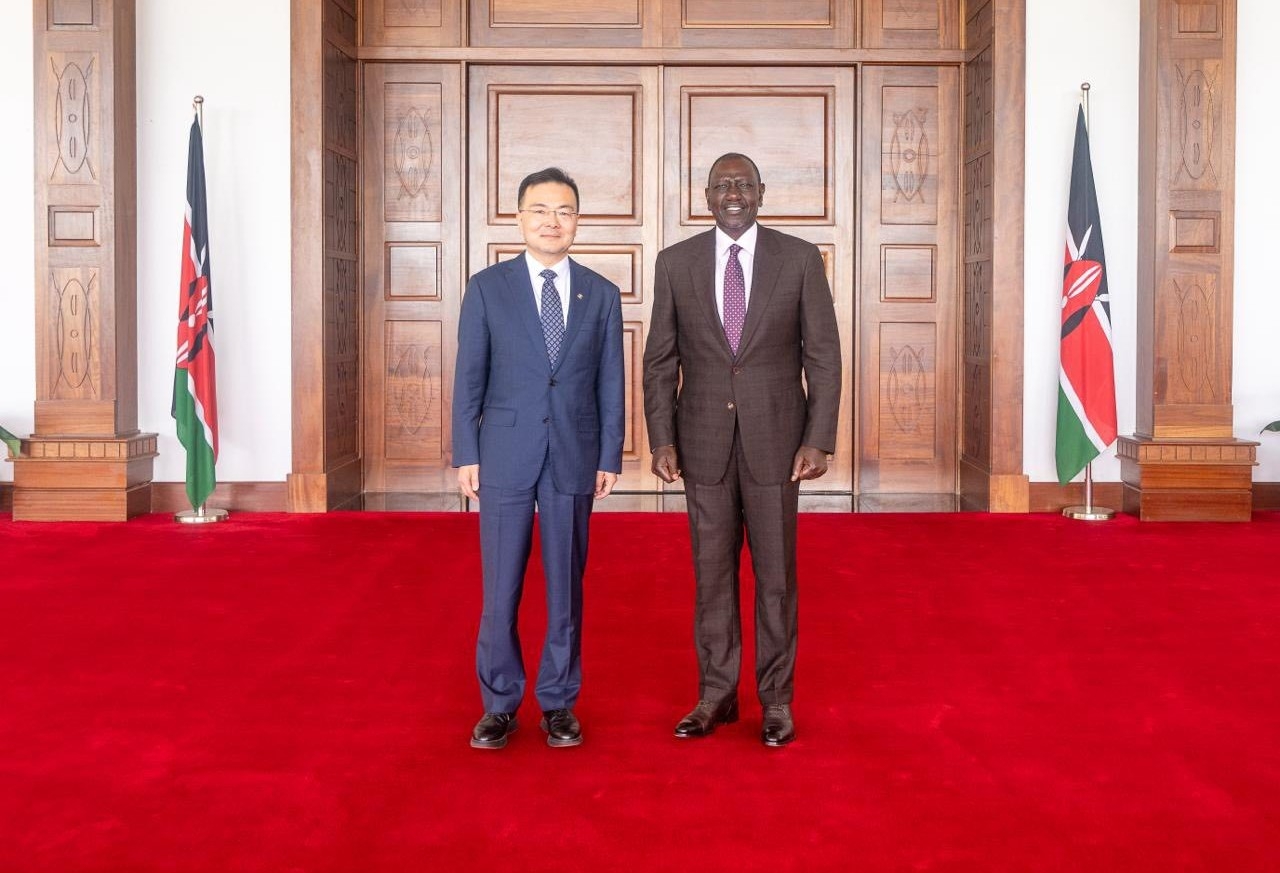

Mark Suzman, CEO of the Gates Foundation.

Mark Suzman, CEO of the Gates Foundation.The Gates Foundation is the world’s largest single donor to the World Health Organization, helping secure key efforts in global health. This week, The Star joined a team of journalists in New York for an in-depth discussion with MARK SUZMAN, CEO of the foundation, on pressing global health issues–from vaccination and maternal health to funding challenges –that directly affect millions of people, including Kenyans.

Question: UN member states have proposed that UNAIDS, the UN agency focusing on the HIV/Aids pandemic, will "sunset", be closed, by the end of 2026. What are your thoughts?

Answer: Reform in the multilateral health architecture, including Unaids, WHO, UNICEF, the Global Fund, and GAVI, is under discussion, particularly with major budget cuts. For example, the World Health Organization (WHO) faces a 20 per cent cut with the US withdrawing funding, making the Gates Foundation its largest single funder.

The UNAIDS proposal is not official yet; it’s a draft for Member States to discuss. Our focus is on ensuring resources continue to reduce the HIV burden, as monitoring, advocacy, and tracking are critical to making progress.

But it is reflective of a broader funding crisis and challenge in the global health community. And it’s one of the reasons why, again, we as the Gates Foundation are doubling down and recommitting our own commitment to the fight against infectious diseases.

And in fact, I should have stressed upfront that the two areas that we are going to stay most focused on over the next 20 years are the reduction in preventable maternal and child mortality, and in the fight against infectious diseases, particularly the aim to eradicate, we hope, polio and potentially, even malaria, and really bring HIV and TB under control to the level of incidence that is the same in high-income countries that is in low-income countries.

And so, we would urge all countries, and then the states that are looking at multilateral reform, to make sure that they keep the goals in mind and make sure that we are funding what is needed to address the needs of the patients.

COVID taught everyone, even those who knew nothing about public health, that one sick person anywhere is a danger to everyone. How can world leaders justify cutting public health funding now? Has Bill Gates’s engagement with the US President made any difference?

There’s no real justification for cutting global health funding. Investments in this area have a clear, measurable impact. While efficiency is always possible, like streamlining supply chains for maternal, child, HIV, or TB commodities, the sector has steadily become more effective over the past 25 years.

Our message to governments is simple: investing in the health and nutrition of your citizens is the most effective investment for long-term development. For global funders, this is both a moral and practical imperative.

We acknowledge debates within countries about balancing domestic needs versus global commitments, but every member state, including the US, has signed onto the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and broader global health objectives. We are actively engaging the UK, Germany, France, and the US to minimise cuts.

Regarding the US, significant reductions have occurred, including the closure of Usaid programmes. Usaid historically played a critical global leadership role and was the largest global health funder for over 25 years. Bill is directly engaging the administration, especially regarding the Global Fund replenishment, where the US has historically funded about a third.

We are advocating strongly, but the ultimate test will be execution and funding decisions. Active debates continue within the administration and Congress, and we aim to maintain strong US leadership in global health.

You mentioned that Gates is speaking directly to President Trump. Is he also engaging fellow philanthropists, given we’re just five years from the SDG deadline?

Yes, we speak to anyone who can help make the case for these investments. That includes heads of state in the US, Africa, and Asia, urging them to increase their own health and agriculture spending. Most African countries, for example, haven’t met their AU budget commitments.

We base our case on facts: these investments are efficient, transformative, and measurable. We can show exactly how vaccines, antiretrovirals, or bed nets reach the people who need them.

Tonight’s event includes other philanthropic partners, and we also appeal to billionaires globally. Bill Gates has committed to giving away over 99% of his fortune; Melinda French Gates and Warren Buffett have pledged similarly. We encourage others to do the same.

But philanthropy can never replace government funding. Relying on philanthropy alone risks letting traditional donors cut their investments. For context, next year our record $9 billion payout is enormous for a foundation, but USAID’s budget last year was $40–70 billion. Philanthropy can’t cover those shortfalls at that scale.

Bill Gates. He has committed to giving away over 99 per cent of his fortune.

Bill Gates. He has committed to giving away over 99 per cent of his fortune.With Gates now the biggest single funder of WHO, following the US pullout, some worry the Foundation could unduly influence WHO’s priorities.

Unlike the Global Fund or GAVI, where we have formal governance roles, the Gates Foundation has no governance role in the WHO or other UN agencies. Decisions are made entirely by member states.

The real way to reduce any perceived influence is for member states to fund the WHO adequately. Our resources are finite – we support public goods, but governance and priorities remain with countries.

Tragically, US withdrawals leave budget gaps, but other member states should increase contributions. Investing in global health is clearly cost-effective: just $10 billion a year could fund pandemic preparedness, yet current investments are far below that. Cuts now are shortsighted; the world underinvests in health, and we continue advocating for stronger support.

How does the Foundation ensure its innovations target the highest disease burdens in Africa and the Global South?

We focus on partnership and alignment with regional bodies, like WHO AFRO, and directly with national governments, because priorities and long-term capacity lie with them. Over the past decade, we’ve expanded our regional presence in Africa and other regions to respond to government priorities in countries like Nigeria, Ethiopia, India, and Sri Lanka.

Philanthropy allows us to take risks on new tools. For example, as resistance to first-generation mosquito nets developed, we funded second-generation long-lasting insecticide-treated nets. Manufacturing includes African producers, while distribution and co-financing are coordinated with the Global Fund and national governments, ensuring sustainability.

Our role is catalytic, not to deliver interventions at scale long-term—that responsibility rests with national governments and intermediaries like the Global Fund or GAVI, which pool funding and negotiate better prices. For instance, antiretroviral and vaccine costs have more than halved due to large-scale purchasing.

Our goal is that by the time we step back, problems like polio will be eradicated, and robust national vaccination campaigns will be fully government-run. In GAVI, 19 countries have already graduated to self-funding. Partnerships are designed for eventual national ownership, and we continue supporting that transition.

Since the Foundation plans to spend down by 2045, how do you balance the urgency to deploy funds with due diligence and ensuring grantee capacity?

That’s an ongoing challenge. We need to balance urgent deployment with the long-term capacity of partners to sustain programmes after we step back. Ultimately, sustainability depends on governments and communities, which is why we emphasise local ownership and leadership.

Our role is catalytic: philanthropy allows us to test innovations and delivery models—whether in health, agriculture, or financial inclusion—without the expectation of long-term service delivery. For example, we trial improvements in poultry, livestock, and dairy to boost productivity for smallholder farmers, who make up most of the rural poor globally.

Once proven, these models are scaled through governments, third-party entities, or the private sector. Across all sectors, we constantly ask: how do we ensure long-term sustainability without our resources? That vision of self-sufficiency defines success.

Five years into your tenure as CEO, how do you assess progress in global health, especially for underserved communities? And how do you address distrust of the Gates Foundation among those communities?

We measure progress by who is actually reached, through vaccines, bed nets, antiretrovirals, and agricultural interventions. The past five years have been challenging. COVID caused major setbacks in vaccination, education, and poverty reduction. We’re only now approaching 2019 levels.

If the pre-COVID trajectory had continued, progress would have been far greater. For example, the SDG target for preventable child mortality is 25 per 1,000; globally, we’re around 31 per 1,000. But outcomes vary widely—conflict-affected areas, particularly in parts of Africa and the Sahel, lag far behind.

As a philanthropic organisation, we rely on willing government partners to implement interventions. We can’t operate in conflict zones, which is where many setbacks occur.

That said, we’ve proven over the past decade that cost-effective interventions can have transformative impacts on health outcomes. Innovations like new TB vaccines or women’s health tools have the potential to accelerate progress further.

The key is rigorous measurement, acknowledging setbacks, and demonstrating a plausible, data-driven path to accelerate progress over the next five years, even amid fiscal and global challenges.

The Goalkeepers event in New York aims to take stock of the progress on SDGs.

The Goalkeepers event in New York aims to take stock of the progress on SDGs.How does the Gates Foundation plan to adjust its communications strategy over the next 20 years to combat misinformation about its activities?

Transparency is key. When Bill announced his commitment in May to give away the bulk of his fortune, part of the intent was to remove suspicion. Some have alleged he’s enriching himself or has investments in pharmaceutical companies, but the Foundation doesn’t invest in major pharmaceutical companies, and all returns go back to the Foundation. That won’t stop conspiracy theories entirely, but we correct facts wherever we can.

Ultimately, national governments and communities must lead. Our role is to work with partners in communities who can validate and speak to the work—they are often more credible than we are. We aim to be fully transparent about our investments and remain open to questions.

Misinformation is especially tough in today’s social media environment, with closed networks like WhatsApp spreading falsehoods. This is a global challenge, not one we face alone. We’re always looking for ways to improve and welcome input on how to combat misinformation effectively.

One area rife with misinformation is the GM seeds, especially the idea that it’s giving foreign companies power over African farmers. How is the Foundation engaging directly with farmers? Are you checking contracts to ensure local partners are involved, so these aren’t just foreign companies deciding what seeds farmers can use?

First, discussions need to be led by African regulators and scientists. We support networks across Africa, but safety and following the science are paramount. Agroecological conditions vary country by country, so regulators must evaluate each case.

Second, we work to build strong local partners. In agriculture, our main delivery partner is AGRA (the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa, based in Nairobi), which supports seed distribution and other initiatives. Most of our investments are in conventional breeding with national agricultural centres and CGIAR, rather than GMOs, and always in coordination with national regulators.

For example, TELA Maize – a drought-resistant maize – is being introduced carefully in Kenya and trialled in Nigeria, following years of regulatory scrutiny.

Finally, farmers need information and support from their governments to make their own choices. Our goal is always to improve smallholder productivity and income. Success is measured by how these interventions directly help farmers and their families, not by intermediaries or companies.

Childhood deaths have been halved over the last 25 years. With vaccines, treatment, and technology, isn’t the next target (to halve deaths again) not ambitious enough?

It’s a great question. My goal is to at least halve child mortality again by 2040, and I’m cautiously confident we can. But it’s harder this time. The biggest gains -from 10 million to 5 million deaths -came from vaccines, and now about 80% of children are vaccinated.

The remaining deaths are more complex: roughly half of the 4.6 million under-five deaths occur in the first month, often within 24 hours. These involve complications like postpartum haemorrhage, respiratory problems, or low birth weight linked to maternal anaemia.

Reducing these deaths requires trained personnel and multiple interventions—not just vaccines. We know the solutions, and we’re confident they can work, but the next halving is more challenging than the first.

Do you believe the countries most affected by the funding crisis can eventually stop relying on international aid? How can that happen over the next 20 years?

There’s no easy path to self-reliance, especially for low-income countries. Even middle-income countries, like Indonesia, took 20–30 years of sustained economic growth and domestic resource mobilisation to reach significant self-funding. Domestic investment in people and health is key, but it’s a long-term process.

The current pullback in global health financing has at least focused finance ministries and heads of state on health budgets, which is a positive outcome. But that doesn’t reduce the need for continued global health investment.

AI is another promising area. We’re exploring its use in health, agriculture, and education, especially for low-resource settings. For example, handheld ultrasound devices with AI can provide near-hospital-level maternal diagnostics in rural areas. AI could also support TB diagnostics, community health workers, and patient self-care, such as helping people in southern Africa manage HIV treatment. These are early but promising interventions, and we’re investing in pilots to test them further.