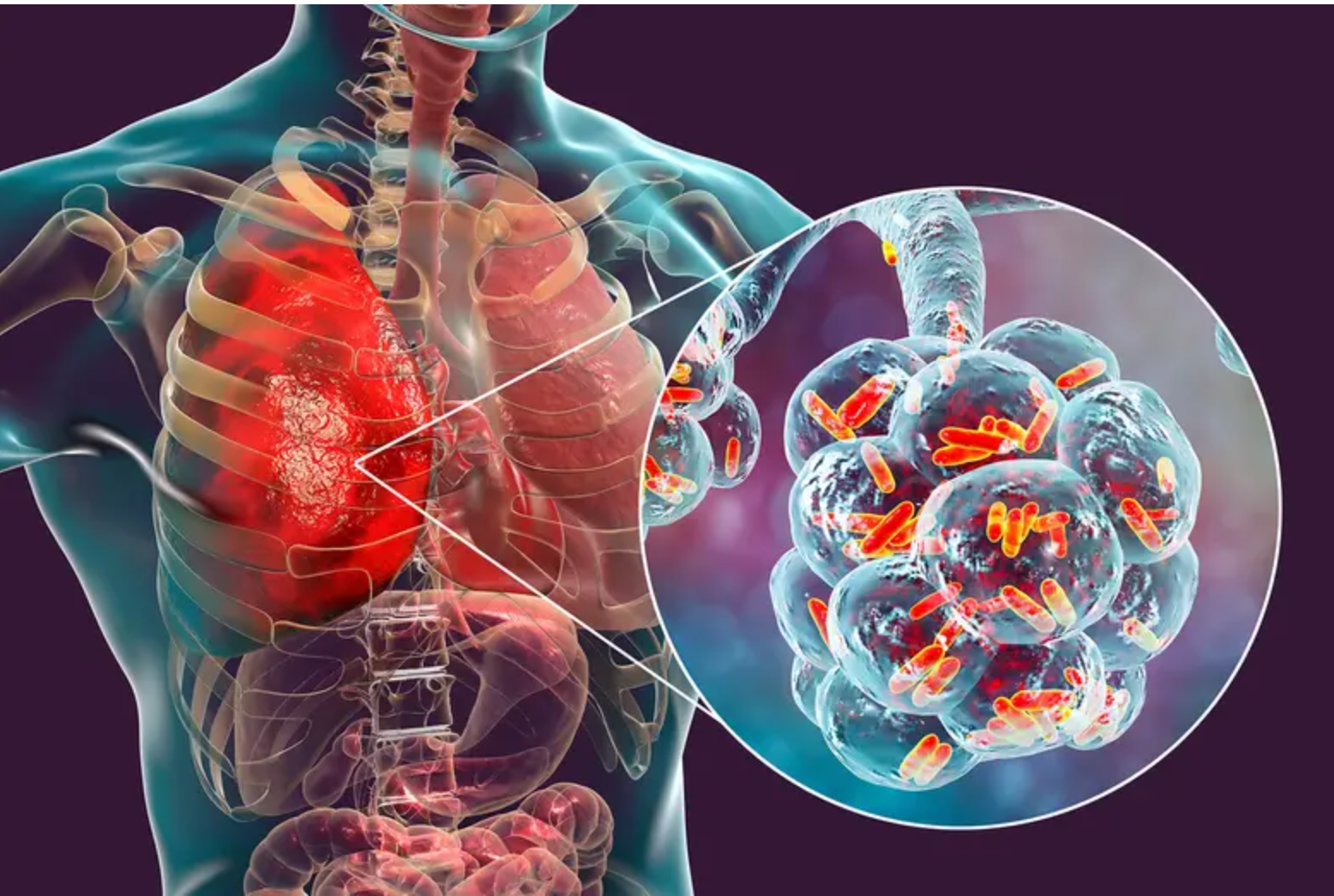

NTM under a microscope. The Kemri researchers called for wider use of modern molecular tests that can quickly tell TB and NTM apart.

NTM under a microscope. The Kemri researchers called for wider use of modern molecular tests that can quickly tell TB and NTM apart.He had completed his TB medication but had again begun coughing, sweating at night, and losing weight.

“I thought I was dying,” Joseph, 42, recalls.

The diagnosis of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB), a severe form of TB that does not respond to the usual medicines, was easy.

Joseph says he was immediately put on heavy TB drugs that he took every morning. But after weeks of treatment, his cough remained, and the fevers never stopped.

He is one of the patients whose sputum samples were collected by the Kenya Medical Research Institute (Kemri) for further testing.

The results were surprising as doctors told him he did not have TB at all. His sickness was caused by a different group of bacteria that mimics TB symptoms and are not cured by the TB drugs. These bacteria are not TB, but they act like TB.

Medics are now beginning to pay attention to these bacteria, called NonTuberculous Mycobacteria (NTM), because they also damage the lungs in similar ways as TB, and even look the same under a microscope. But the crucial difference is that TB medicines cannot cure them.

“The Ministry of Health should strengthen national TB control programmes to include surveillance for NTM infections, particularly in HIV-endemic regions,” said Kemri scientists, led by Albert Okumu, a microbiologist at the Centre for Global Health Research (CGHR) in Kisumu.

Okumu and his team collected 3,161 sputum samples from public health facilities in 14 counties in western Kenya from March to October 2022, to test them for TB drug susceptibility and for archiving of identified TB bacteria.

The samples were donated by adult patients attending TB clinics.

“Based on the estimated prevalence of MDR-TB among retreatment cases in Kenya (5–10 per cent), and considering our laboratory capacity, 155 sputum specimens meeting the inclusion criteria were selected for processing,” the team explained.

All of them were thought to have drug-resistant TB. But the test results were startling. “The overall prevalence for both NTM (the TB copycat) and MTBC (mycobacterium tuberculosis complex, the bacteria that actually cause tuberculosis) was thus, NTM (63.9 per cent) and MTBC (19.4 per cent),” the study reports.

This means that almost two out of every three patients in the study who were thought to have resistant TB actually had the copycat bacteria.

Tuberculosis is caused by one specific germ known as Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It spreads from person to person through the air.

More than 120,000 Kenyans develop TB every year, and the disease accounts for 3.2 per cent of all deaths, according to the Ministry of Health.

NTM, on the other hand, is a large family of bacteria found in the environment. They live in soil, in water, and even in household dust. People usually breathe them in from the air or get exposed through water droplets.

Unlike TB, NTM does not spread easily from one person to another and most healthy people can fight it off. But in some cases, especially if someone already has lung problems or if their immune system is weak, NTM can cause serious disease.

“Data on NTM in Africa remain scarce due to limited diagnostic infrastructure and underreporting,” Okumu and his colleagues said in their new paper in the Journal of Clinical Tuberculosis and Other Mycobacterial Diseases.

They noted that both TB and NTM can cause long-term lung infections. Both can bring the same signs, such as cough, chest pain, fever, night sweats, and weight loss. This makes it difficult for doctors in high TB areas to know which one a patient really has.

“Since NTM infections and tuberculosis share clinical features—cough, weight loss, radiographic abnormalities—misidentification in high–TB-burden settings is common, complicating patient management,” the researchers said.

They identified 11 different species of NTM. The most common were Mycobacterium intracellulare, M. fortuitum and M. scrofulaceum. Some of these species are harmless to most people but can cause serious lung disease in those who are sick or weak. Some are hard to treat because they resist many antibiotics.

They said that “Treatment of NTM remains challenging, particularly due to resistance among rapid growers such as M. abscessus complex.”

Their tests found NTM was most common in men, especially those in their thirties and forties. Surprisingly, NTM also appeared more often in patients who were HIV-negative.

The World Health Organization has set ambitious goals to cut real TB cases in half by 2025. By 2035, the goal is to reduce cases by 90 per cent. But progress has been slow.

The WHO says that in many countries, patients are not correctly diagnosed. Some with TB go undetected, while others, like Joseph, are wrongly treated for TB when they have NTM.

The Kemri researchers called for wider use of modern molecular tests that can quickly tell TB and NTM apart. They also recommended including NTM in Kenya’s TB control programme, since the two diseases are often confused. “Adequate TB/HIV integration and management, use of molecular techniques, and accurate identification are critical,” they said.

Their report is titled: “Distribution of nontuberculous Mycobacteria among presumptive drug-resistant tuberculosis patients from a Ministry of Health drug resistance surveillance program, in western Kenya.”

The co-authors are Kemri’s Ochieng John, Tonui Joan, Odhiambo Ben, Sitati Ruth, and Wandiga Steve.

Others are Odeny Lazarus of Amref- Health Africa; Ogoro Jeremiah of the Ministry of Health’s National Tuberculosis Programme; and Collins Ouma of Maseno University.

The US Centres for Disease Control (CDC) says NTM are resistant to many antibiotics, making infections more difficult to treat.

“Treatment

varies but often requires a combination of two to three antibiotics for six

months to a year or longer,” CDC says.