An image of a pill camera that a patient swallows. It is excreted alongside waste and cannot be reused. It costs about Sh50,000.

An image of a pill camera that a patient swallows. It is excreted alongside waste and cannot be reused. It costs about Sh50,000.Would you swallow a video camera? Well, 72 Kenyans did, and this is what doctors found.

Over five years, a clinic in Nairobi quietly led one of Sub-Saharan Africa’s first diagnoses using a video capsule endoscopy (VCE). This is a pill camera that patients swallow, to allow doctors to see deep inside the small intestine, a section that traditional scopes often miss.

The Nairobi results, recently published in the Journal of Tropical Medicine, are eye-opening not just for what the cameras found, but also for what they mean for the future of medicine in Kenya.

This is the first study from Kenya that documents the experience of VCE use in clinical practice.

Gastroenterologist Dr Werimo Pascal Kuka and five colleagues analysed medical reports of 72 patients who underwent the procedure at the Nairobi-based Gastro and Liver Center at different times between 2017 and 2022.

All of the patients reported gastrointestinal problems and had previously endured upper and lower endoscopy, which did not pinpoint the cause of the trouble.

Before swallowing the camera (the size of Panadol), the patients were placed on a low-residue diet for 24 hours and fasted for the last six hours.

They then swallowed the smooth, capsule-sized device containing a miniature camera, lights, battery, and transmitter.

As it travels naturally through the digestive tract, the capsule takes thousands of pictures and videos, sending them in real-time to a recorder worn on the patient’s waist.

Pill cameras are widely used in high-income countries, but are rarely used in Africa due to cost. Each pill can cost about Sh50,000.

Dr Kuka and colleagues said the patient could continue normal physical activities as the capsule moved silently through the digestive system within 24 hours, taking pictures and shooting videos.

It is eventually excreted with waste and can not be reused.

Medics sit to review the images only after the capsule is excreted, uncovering hidden ulcers, bleeding vessels, tumours, or even worms.

Dr Kuka’s team said this is the most tiring part. “Drawbacks for such a setup include lack of multidimensional images, inability to manipulate the capsule, absence of interventional capability, and physicians’ fatigue in reading frames,” they noted in their paper, titled “Indications and Outcomes of Video Capsule Endoscopy in Sub-Saharan Africa: A 5-Year Single-Centre Experience in Nairobi, Kenya.” It was published late last month.

Their findings? The diagnostic yield was 77.8 per cent, meaning the capsule revealed a meaningful cause of symptoms in more than three out of four patients.

The top reason for undergoing the capsule test was unexplained gastrointestinal bleeding, followed by abdominal pain, anaemia, and changes in bowel habits.

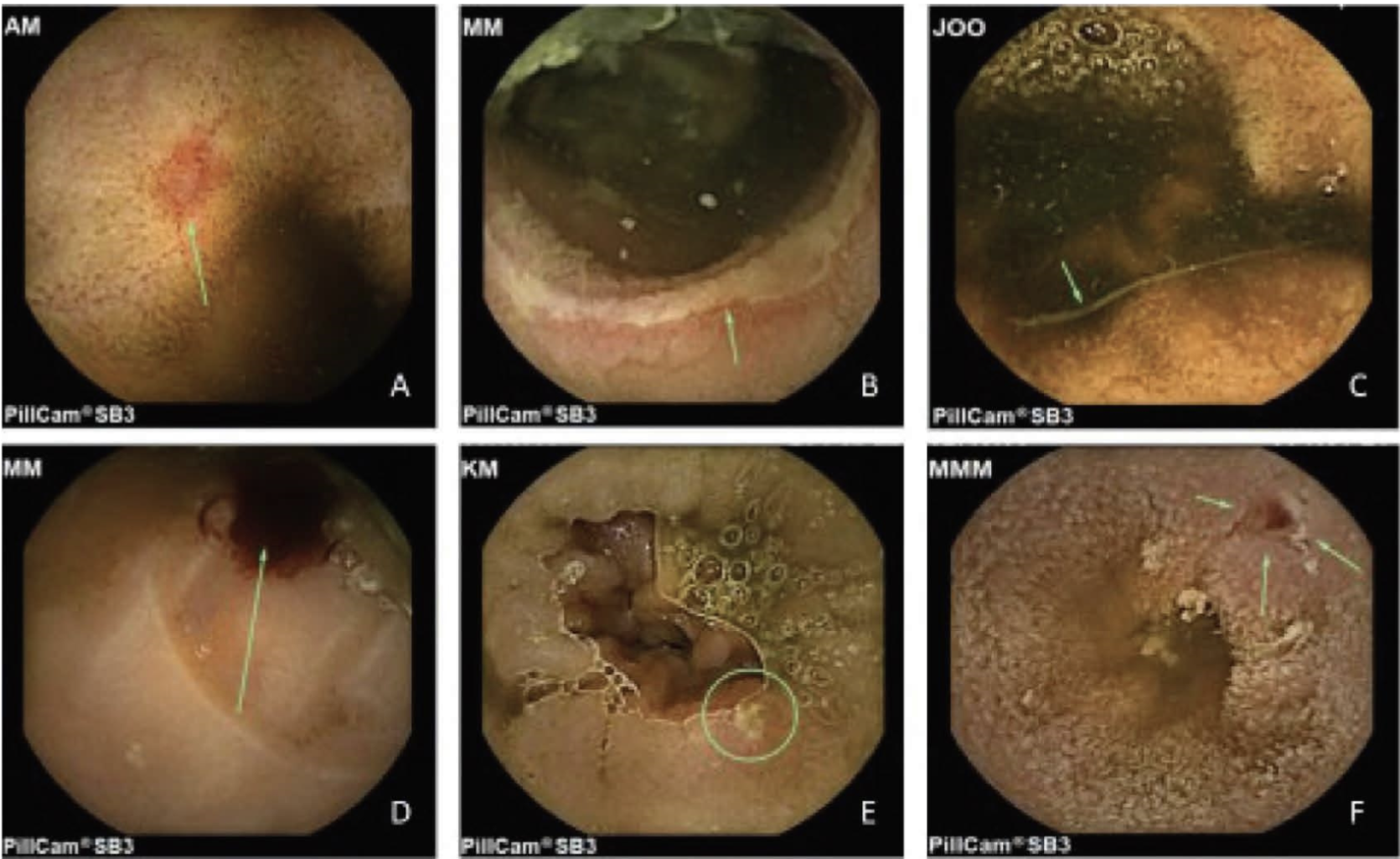

Images of the gut, with visible wounds and blood spots, from the reels of the camera.

Images of the gut, with visible wounds and blood spots, from the reels of the camera.In these patients—many of whom had already endured CT scans, colonoscopies, or barium studies without answers—the camera changed everything.

One of the most striking findings was angiodysplasia, a condition where fragile blood vessels in the gut leak or rupture. It was the most common cause of bleeding, seen in over 35 per cent of cases of both overt and occult gastrointestinal bleeding.

But there were also diagnoses unique to the African setting. Suspected intestinal tuberculosis showed up in 5.6 per cent of the patients. Two others were found to have worms in their intestines.

There were even suspected cases of Crohn’s disease, a chronic inflammatory bowel disease once considered rare in Africa, but now reportedly on the rise. And in a handful of patients, the capsule revealed polyps or masses. Some of these required further investigation for possible cancer.

Dr Christopher Opio, a consultant gastroenterologist at Aga Khan University Hospital, says the camera pill has many benefits over traditional endoscopy and colonoscopy, where doctors use a camera attached to a wire to study the gut.

“It's one of the only tests that helps your doctor examine your whole small intestine and large intestine,” he said when the Aga Khan introduced the procedure. Dr Opio did not take part in the current study.

“Other diagnostic procedures (such as an endoscopic ultrasound) use a thin, flexible tube with a camera. But the tube can only reach the first six feet of your small intestine,” he explained.

The pill camera is not completely risk-free. Technical problems can include short device battery life and download failures from the recorder.

One rare complication is capsule retention when the swallowed

device does not pass out of the body within 72 hours. This can happen if

something is blocking part of the gut, like inflammation, narrowing, or tumours.

Two patients in the Nairobi study suffered capsule retention.

“In one patient, the capsule was retained in the stomach for more than six hours and required endoscopic manipulation for its passage into the duodenum,” the medics explained. “The second patient had non passage of the capsule after 72 hours of ingestion. The patient had no complaints suggestive of intestinal obstruction. A subsequent CT abdomen performed a week after the procedure showed no capsule, suggestive of spontaneous passage.”

The other medics in the Nairobi study are Eric Murunga and Gloria Mugo of the Gastro and Liver Centre; Emmanuel Oluoch of the Aga Khan University Hospital; and Nelson Onyango of the University of Pennsylvania and Kof Clarke of the Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center.

The idea of a swallowable camera was first floated in the 1980s by Israeli engineer Gavriel Iddan, who partnered with gastroenterologist Eitan Scapa. Their invention received the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in 2001. The first patient swallowed the device in 1999.

Capsule endoscopy has spread around the world since then.

Dr Opio said doctors now use it to investigate the cause of gastrointestinal bleeding, diagnose inflammatory bowel diseases, such as Crohn's disease, and diagnose gastrointestinal cancers by showing tumours in the small intestine or other parts of the digestive tract.

“Capsule endoscopy has also been approved to evaluate the muscular tube that connects your mouth and your stomach (oesophagus) to look for abnormal, enlarged veins,” he said.

The Nairobi medics said they did not perform a cost analysis of VCE, which is a vital factor that public and private health managers consider before VCE can be integrated into regular practice in the region.

But they do not recommend wide application in patients with only one symptom. For instance, 71.4 per cent of patients with just abdominal pain had normal findings on VCE.

“Given the relatively low pathology

identification rate, we recommend that VCE should not be considered as a

diagnostic tool in patients with the sole complaint of abdominal pain,

especially in resource-limited environments,” the medics wrote.