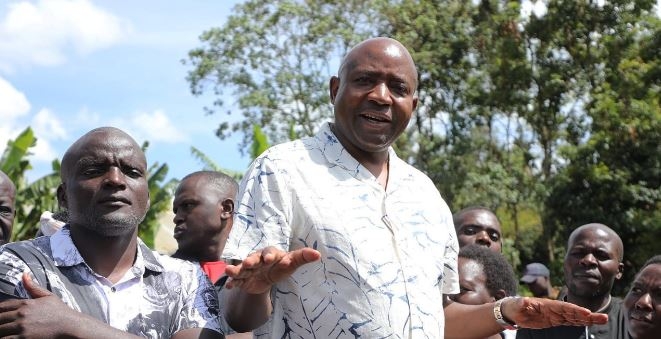

Eligible Kenyan athletes at a training camp. Those sanctioned said that once the ban is announced, public vilification is relentless. Photo/ File.

Eligible Kenyan athletes at a training camp. Those sanctioned said that once the ban is announced, public vilification is relentless. Photo/ File.“I started shaking. ‘Like how?’ I was confused…The only thing I remember is going inside the house, coming outside the house, and then my wife asked, ‘What’s wrong?’ I was shaking. It [had] a huge impact,” he recalls.

Confusion and fear followed: he did not know whom to trust or what to believe. In the lonely days that followed, dark thoughts crept in, and late one night, he questioned why he should go on.

Extensive interviews with Kenyan track and field athletes who faced doping bans confirm that this despair is common. Seven out of ten athletes interviewed reported having suicidal thoughts during their ban.

One said: “I remember thinking, ‘Why don’t I just die?’ I even contemplated throwing myself from the top of the building and letting everything come to an end”. Another athlete said bluntly, “In the third month, I felt like things were at a climax, so I tried committing suicide”.

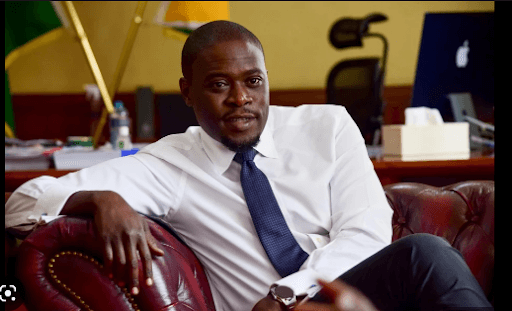

The interviews form part of a new study by Kenyan researcher Dr Byron Juma and US-based Jules Woolf, published last week in the Performance Enhancement & Health journal.

The study uncovers what happens to Kenyan athletes after a

doping ban. The authors write that “many reported psychological struggles,

including suicidal thoughts, with one requiring psychological intervention

after a suicide attempt.”

Seven of the ten Kenyan runners interviewed admitted to thinking about ending their lives. Athletics is the main income earner for most athletes, and most described persistent anxiety about their future and their ability to support themselves and their families.

The authors warn that mental ill health is worsened by abandonment by Athletics Kenya (AK), the federation overseeing track and field, which immediately cuts ties, citing a policy of non-engagement with sanctioned athletes.

“When you are sanctioned, you are alone. I don’t think AK will listen to you,” said one athlete, who claimed AK stopped answering his calls.

Two other athletes also received no response when they sought help. Anti-doping officials echoed athletes’ concerns. One official of the Anti-Doping Agency of Kenya (Adak), who has worked at the agency for five years, acknowledged that AK distances itself from sanctioned athletes and admitted the absence of psychological support.

ADAK is the national body responsible for catching and prosecuting individuals involved in doping in Kenyan sports. It collaborates with the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) and the Athletics Integrity Unit (AIU) to test athletes, investigate violations, and issue sanctions.

The official’s observations reflected the anti-doping community’s awareness of the mental and emotional strain sanctions cause, yet do little or nothing about it.

“AK’s limited support may reflect Kenya’s deep talent pool, which stretches resources, forcing AK to prioritise eligible competitors over sanctioned ones. Without institutional support, sanctioned athletes faced not only emotional isolation but also the abrupt collapse of their professional livelihoods,” the authors said.

Dr Juma, the lead author, is an assistant professor and programme coordinator in sport leadership and recreation at the US's Emporia State University. Dr Woolf is a researcher on the management of drugs, sport, and health at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

The athletes said that once the ban is announced, public vilification is relentless.

Some athletes were mocked with nicknames tied to the substances in their cases. “These nicknames, often used by peers or community members, served as a constant reminder of their violation. For instance, WanjalaM (name changed) was greeted by the name of the supplement linked to his sanction, while MusyokaM (name changed) was dubbed ‘Mr. [substance]’ after testing positive for a Beta-2 Agonist. Over time, such labels affected their identities, with MusyokaM noting how he was repeatedly referred to as ‘the [type of] person who uses drugs,’” the study authors said.

The punishment spreads far beyond the athlete. “When you sanction them, it is not only the athlete who suffers, but also the immediate family, the extended family, and the community,” an anti-doping official observed. Athletes who once supported whole households suddenly face shame and financial ruin. Children watch their parents crumble.

“While no definitive conclusions can be drawn, Kenyan athletes’ concerns for their children underscore the urgent need to examine and mitigate any potential impacts of sanctions on these ‘unseen victims’. This represents a novel direction for future research, offering a family systems perspective on the consequences of anti-doping enforcement,” Dr Juma and his colleague said.

Their paper is titled, "The hidden cost of doping sanctions: examining the experiences of Kenyan athletes sanctioned for violating anti-doping rules."

Many athletes said they turned to alcohol. “MusyokaM (a former long-stance runner) shared that he would hire a motorbike rider to deliver alcohol and drink with him, saying they would ‘just laugh about nothing.’”

Under WADA’s strict liability rule, athletes are responsible for any banned substance found in their bodies, even without intent. The study notes that this principle “makes successful appeals seem futile, leaving athletes feeling powerless.” The result, researchers say, is deep hopelessness and mistrust.

The rule states that “it is not necessary that intent, fault, negligence or knowing use on the athlete’s part be demonstrated to establish an anti-doping rule violation.”

Dr Damaris Ogama, a Kenyan lawyer and researcher on doping interventions, said this rule potentially leads to unjust punishments for innocent athletes who ingest prohibited substances inadvertently.

“Contamination of supplements is becoming an acute problem. Research has found that certain vitamins and protein powders contain additives that are not declared because of poor manufacturing standards. An athlete who consumes such a product in good faith may end up testing positive and suffer career-threatening ramifications,” she wrote recently.

About 257 Kenyan athletes have been sanctioned for doping since 2017, according to the Athletics Integrity Unit, which enforces rules in track and field games. A total of 19 Kenyans have been banned in 2025 alone.

Despite the despair, many Kenyan athletes have refused to give up the sport that defined them. “Kenyan athletes expressed a strong desire to return to competitive sport, with some successfully re-entering competition and others transitioning to ASP (Athlete Support Personnel, such as coaching) roles, reflecting a continued sport commitment.”

Some used the ban period to pursue education or farming, others to coach younger runners. One athlete said the experience had “opened your mind and made you think outside the box.”

Dr Juma and Woolf called for authorities to provide mental-health services and coping skills to help athletes manage their post-sanction identity disruption and stigma and potential return to sport.

They said the wider consequences of sanctions on athletes’ families should prompt sports organisations to also focus on the needs of athletes’ families and offer targeted interventions to aid reintegration or separation from sport.

They argue that doping bans should protect sport’s integrity without destroying human lives.