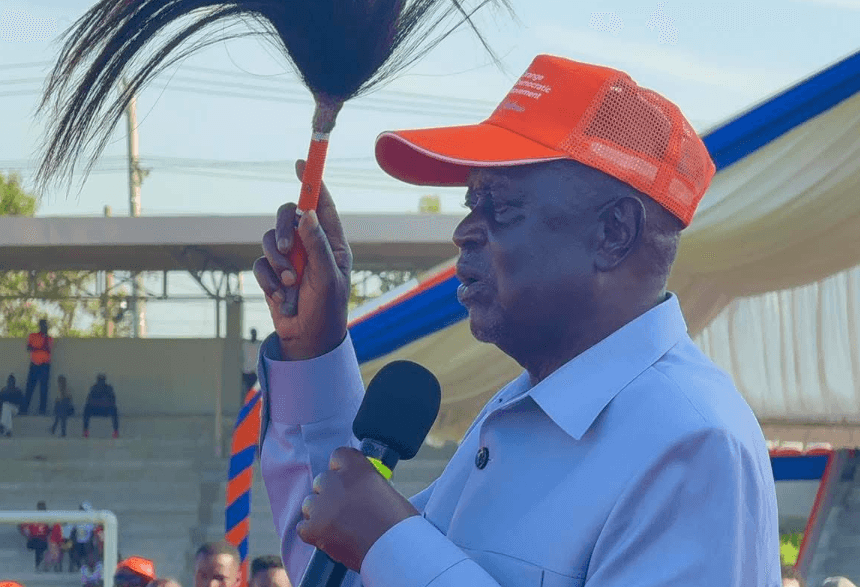

Najma Ahmed during the interview in Mombasa / BRIAN OTIENO

Najma Ahmed during the interview in Mombasa / BRIAN OTIENOGiven a choice, Najma Ahmed will choose Kenya all over again.

She says the country has given her peace of mind, so much so that she is now trying to give other mothers peace of mind.

She understands the pain mothers with children with Down syndrome, autism, cerebral palsy, and other intellectual and growth disorders go through.

She has lived with that ‘pain’ for 19 years and would not wish that on her worst enemy.

Najma has a 19-year-old son, who was diagnosed with Down syndrome as soon as he was born.

Down syndrome is a genetic disorder caused by the presence of an extra 21st chromosome, leading to developmental delays and distinct physical features.

There are three main types: Trisomy 21, where every cell has three copies of chromosome 21; translocation, where extra material from chromosome 21 is attached to another chromosome; and mosaic, where some cells have two copies of chromosome 21 and others have three.

Symptoms vary from person to person and can include intellectual disability, heart defects and characteristic physical traits like a flattened facial profile.

A Somali who lives in Mombasa, Najma is an advocate for the rights of children with special needs, and also does family counselling and therapy for special needs children.

She has been working with children with special needs for the past eight years.

“I have seen how the community lacks awareness about these children. This is what brings stigma, which is why I started working with special needs children,” she says.

The first stigma usually comes from one’s own family, especially when they don’t accept that one of their own has special needs.

“Our children have been neglected in so many ways. First, we have to start at the families. Families have to accept them first for them to get help and accepting is the hardest thing because it comes in different levels,” she says.

Once the family accepts, it becomes easier for the community to accept the children.

“Our communities don’t understand how we feel as mothers and what we go through every day and they believe our children cannot do anything in life but these kids have hopes and dreams,” she says.

Najma says the majority of special needs children have special abilities that normal children do not have.

“There are a lot of famous people who had disabilities but who have created things. One of the founders of Twitter, now X, Jack Dorsey, had a significant stuttering problem, which made communication difficult,” she says.

Famous comedian Steve Harvey also had a significant stammering problem.

“Today, they stand and hold a big role in society,” she says.

She says when she gave birth to her son, she was young and did not know anything about Down syndrome.

“It was a baby surprise. No one told me anything during the prenatal scans, although in most cases children with down syndrome can be seen as early as five months during pregnancy,” Najma says.

“As soon as I gave birth, a paediatrician came to the ward and asked me, ‘what do you know about your child?’. I was like, ‘Nothing. Why?’. He didn’t want me to panic, so he said, ‘Okay. It’s fine.’”

Raising her son was hard, she says, because such children’s immune system is low and they get sick easily, but they improve as they grow up.

Education-wise, they grasp things much slower than normal children.

“I gave all my time to him. I had to stop working, stop studying to concentrate on him,” she says

She is lucky her family eventually came to accept him, especially her (Najma's) mother, who became his best friend.

Once she gathered enough information about Down syndrome she started raising awareness about the disorder.

“You can see a lot of parents who don’t understand what Down syndrome is and I didn’t want parents to go through what I went through,” she says.

Today, it is easier to get information on the disorder because of the advent of social media, she says.

In 2023, she came up with the '#Don’t Hide Me’ campaign with the primary goal of creating awareness on the plight of children living with special needs and harnessing efforts to support their growth, inclusion and integration in society.

The campaign is run as a special programme by Safe Surgical Aid (SSAID).

She says in Kenya, most of these children are hidden in boarding schools or in houses because of outdated cultural issues some of which threaten their lives.

“These kids are clever. They have their own ways of learning and their own ways of doing things. So, we need to take them out,” she says.

She and her son go everywhere together.

Najma says children with special needs are very sensitive and learn very fast socially.

“Speak to them nicely because special needs have sensitive hearts. Even when they cannot hear you, they can feel or sense you. That is why I always advise that people speak to them nicely,” she says.

She says one day, he reported to his grandmother that Najma and her husband had a fight.

“When I got to my mother’s place the first thing she asked is what we were fighting about. I got surprised and asked her how she knew. She said my son told her and I could not believe at first until she asked him to repeat what he had told her,” Najma says.

She says when she got to Mombasa, she first had a chance to do her advocacy work at the Kwale Mentally Handicapped School in Kwale county.

“That name really hit me badly, as a parent, and I was traumatised by it for long. I made a promise to myself that I would do bigger project for these kids,” Najma says.

She says calling the special needs children mentally handicapped is demeaning and together with Safe Surgical Aid they wrote a protest letter to the Education ministry.

To their surprise, the ministry on October 7 responded positively to the letter with express directives to all regional, county and subcounty directors of education to ensure change of terminology from “Schools for Mentally Handicapped Learners” to “Schools for Learners with Intellectual and Development Disabilities”.

The letter, written by Education PS Julius Bitok, was copied to the Teachers Service Commission.

The PS said Kenya ratified the United Nations on the Rights of Persons wIth Disabilities (UNCRPD) in 2008.

“Article 8 (1)(b) of the convention mandates member states to combat stereotypes, prejudices and harmful practices,” Bitok said in the letter.

Najma says it is also her wish that children with special needs also get free medical attention from the government, because they need a lot of support due to their health.

“Because of the costs, most parents with special needs children cannot afford SHA. If the government can lift that burden from them, I would be the happiest person on the world,” she says.

“The only disability in life is a bad attitude.”

In 2024, Safe Surgical Aid and #DontHideMe did a medical camp at Garissa Special School in Garissa county and 61 per cent of the patients that came had more than one disability.

And 92 per cent of the children who visited the camp had no right documentation for registration with the National Council for Persons With Disability.

They have done several other medical camps in Wajir, and they will be in Mandera soon.