Apart from his family, few other people have seen him without his signature dress code - a white kanzu.

“My wife had given birth to our third born and I was dressing up to go to the hospital. I could not find the best matching outfit to wear and got angry," the 74-year-old fiery human rights activist says.

“I then decided to pick the nearest kikoi, underwear, a vest and one of my kanzus. I felt so comfortable that I wondered why I should bother myself with any other outfit. That was when I started wearing kanzus every day.”

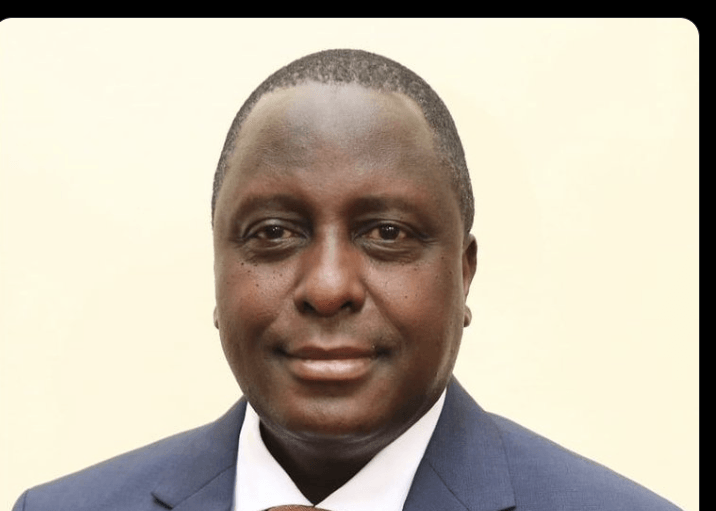

Meet Muslims for Human Rights director Khelef Khalifa, a man whose fight with the Moi government saw his dear friends including Siaya Governor James Orengo think his days on earth were numbered.

He has gone through harrowing experiences in his quest for justice for Kenyans at the Coast and beyond. A movie about his life in the quest for justice would likely win an Oscar.

Few know it, but without him, Mombasa residents would not be boasting of the Mama Ngina Waterfront Park, which had been given out by the Moi regime.

President Moi had allocated the park’s land to two churches, African Inland Church and Baptist Convention.

Luckily, around 1994 the Mombasa municipal council had only Muslim councillors.

So, every time the churches would take construction plans for the park for approval, the council would reject them.

President Moi got angry and called then Mombasa Mayor Ahmed Mwidani, asking if Kenya had two governments.

In a huff, Mayor Mwidani called a special meeting of the council and approved the building plans and the construction of a perimeter wall around the park began.

“In the headlines, the papers said ‘Gone! Gone! Goooooone!’ I said no. I would not accept it. I bought sledge hammers, and went down to the park. I had mobilised seven of us including Munir Mazrui, Caleb Ng’wena and a few others,” Khalifa recalls.

They climbed the perimeter wall and started demolishing it, attracting a huge crowd.

“The moment the media crew came to the scene, people descended on the wall like locusts,” he recalls.

Police then arrived and all people ran away leaving Khalifa, who went on demolishing the wall unperturbed.

“The angry OCPD shouted at me, ‘Who gave you permission to demolish the wall?’ And I replied, ‘Who gave them permission to build the wall on public land?’ We were arrested and taken to Urban police station.”

The next day they were taken to court and a hearing date set. At the hearing, none of their lawyers appeared and Khalifa had to represent himself.

“I gave a performance at a packed court, shouting at the top of my voice. Needless to say that case took years but eventually the land was reverted to the public,” Khalifa says.

He started his activism in the early 1990s during the clamour for multi-party democracy, inspired by the fiery preacher Sheikh Khalid Balala of the Islamic Party of Kenya.

“The impact he had not only on me but the whole of Kenya was immense. When he stood at Mwembe Tayari to openly rebuke the then President Moi, calling his name, it was something shocking. It was unheard of,” he said.

Khalifa became part and parcel of the radical IPK, whose activities, he said, were most of the time spontaneous.

One day, they planned a demonstration from Sakina Mosque, the base of IPK in Majengo, to Uhuru na Kazi building, the regional headquarters of the administration.

However, they did not know that very day President Moi was coming to down to Mombasa.

The security panicked and tried to dissuade the party, whose chair then was current Changamwe MP Omar Mwinyi, not to hold their demonstration. They told them the presidential security was ruthless and there would be over 200 deaths.

"Omar Mwinyi also panicked and called us, including Prof Alamin Mazrui, to try and cool the youth. But we were very adamant because demonstration was our right.

“Omar Mwinyi even panicked more, saying he thought calling us as the older people would save the situation, but we are even more radical than the youths,” Khalifa recalls.

The demonstration went on as planned.

“It was so tense. Some of us suggested instead of going to Uhuru na Kazi building, we go to the airport where President Moi was to land. But what surprised us all, at the last minute, Moi decided to take a chopper from the airport to State House Mombasa upon landing.

“He didn’t want confrontation. People had lined up the streets waiting to welcome Moi as was the custom, but instead they saw demonstrators shouting ‘Takbir! Allahu Akbar!’”Khalifa says.

He says in as much as Moi was a dictator, he had demonstrated true leadership that time.

“If it was during the leadership of Uhuru Kenyatta or William Ruto, probably there would have been a bloody confrontation,” he says.

Still in the 1990s, he recalls another harrowing incident during the first anniversary of the storming of Mwembe Tayari’s Shibu Mosque.

Political activists like Orengo and former Deputy Speaker Farah Maalim were in the mosque for the celebrations, with charged youth ready to go to the streets.

A week earlier, the Central Organisation of Trade Unions had unsuccessfully called for a national strike to protest a myriad of things including poor government services and low pay.

“I went to Orengo and asked him, ‘Jimmy, if we called for a strike in Mombasa here, would we be breaking the law?’ He said, no. I talked to the preachers and we came to an agreement. It was then announced that we would strike and no one was to work,” Khalifa recalls.

The government got wind of the plans and started contacting the businessmen asking them not to close their shops and business, assuring them of safety. This did not work.

On the day of the strike, all shops were closed and Mombasa was at a standstill.

“We got word that most of the IPK leadership would be arrested. So, that day I left for home, removed my kanzu and wore a blue jeans and a shirt, complete with a cap. Nobody recognised me and I walked around the streets. All other leaders of IPK were arrested. I was not.”

Police went to search for him in his house but he was out. He had decided to sleep in another location.

Around 1994 when IPK started losing ground, Khalifa co-founded Safina Party together with Richard Leakey, Paul Muite, Bob Shaw, Farah Maalim, Muturi Kigano and Kabando wa Kabando, among others.

Safina by then was not registered and thus were not supposed to open an office anywhere else apart from Nairobi.

But Khalifa wanted media attention and he came up with an idea to ‘open’ an office in Mombasa.

He approached a friend in Old Town and rented out his restaurant for Sh32,000, which was a lot of money then.

The restaurant was supposed to act like a party office for the purposes of the media attention.

However, the government got wind of the intended plan and Special Branch head Shukri Baramadi approached Khalifa to dissuade him, promising to take him to see President Moi and tell him whatever he wanted.

“I told him Moi will offer me three things – threats, land or money. I was not interested in meeting Moi. In the end he told me he would arrest me. I told him no problem,” Khalifa recalls.

He then took a flight to Nairobi and met Bob Shaw, and told him of the incident with Baramadi, believing he would be arrested.

On the eve of the party branch 'launch’, Khalifa was arrested at around 1pm and taken to Urban police station, before he was transferred to the Port police station.

At around 2am, a police van picked him up and took him to Makupa police station, where he was bundled into another car and driven to Tudor Norah, where he lived.

“I asked Cheruiyot, the head of the police delegation then, where we were going and he told me to search my house. I asked them if they had a search warrant and they said they did not need any. I told them they would not search my house without it,” Khalifa says.

Then Cheruiyot asked Khalifa whether they should go back and he agreed. The police boss ordered the driver turn around and they went to Buxton estate.

There, about six more police vehicles arrived. They beat Khalifa senseless.

“The streets of Mombasa had been plastered with Safina posters. This irked the government and was the reason for my harassment.

“While they were beating me, I heard one of them telling the others they should take me to the Nyali bridge and throw me into the sea and claim I escaped from their custody and they didn’t know where I was. That was the time I felt I was really going to die,” Khalifa remembers.

However, he thought if police had any intention of killing him, they would have done it by then.

“I told them a man has to die one day and if it was my time, then so be it. They were shocked and said I was more stubborn than Sheikh Khalid Balala. But, I tell you, I thought I was going to die.”

From there, Khalifa was driven to Kijipwa police station in Kilifi county where he stayed until noon when a delegation of his colleagues, including Muite, sought his release.

He was freed and they were escorted to Moi International Airport from where they flew to Nairobi.

“We came to know later that Richard Leakey had an audience with then British High Commissioner, who was raising concern that Safina was dealing with Islamic hardliners, which was not true. Leakey then let slip the intended opening of the Mombasa branch of the party.

“The British High Commissioner had an audience with Moi and told him of the plan. Moi was furious and ordered the Special Branch to deal with me. For us it was a media blitz,” Khalifa recalls.

He says most people think human rights activism is normal work. It is not, he says.

“It involves a lot of risk. When you talk about corruption, it means you are trying to interfere with people’s benefits. They will not let you do it,” he says.

The father of five, three daughters and two sons, says his wife was not worried about his life during the Moi regime. She only became worried after Uhuru Kenyatta took power.