The Non-State Armed Groups or militia groups in Africa can be understood by the ethnic nature of groupings in Africa, and the fight for territoriality.

However, territoriality is not only associated with spatial and social grouping but also with interests, betrayal, cooperation, conflict, anxieties, and uncertainty among individuals, groups, and nations. This can be explained by the game being played within the international system.

The call for the deployment of the Eastern Africa Standby Force by President Uhuru Kenyatta [in his capacity as EAC chairman] demonstrates such uncertainties, anxieties, cooperation, and conflict of interest.

The call for deployment came after the admission of the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the East African Community on March 29, 2022. If it comes to a realisation, the deployment will create anxieties between Nairobi and Kigali administrations, and will escalate the anxieties and diplomatic tension between Kigali and Kinshasa.

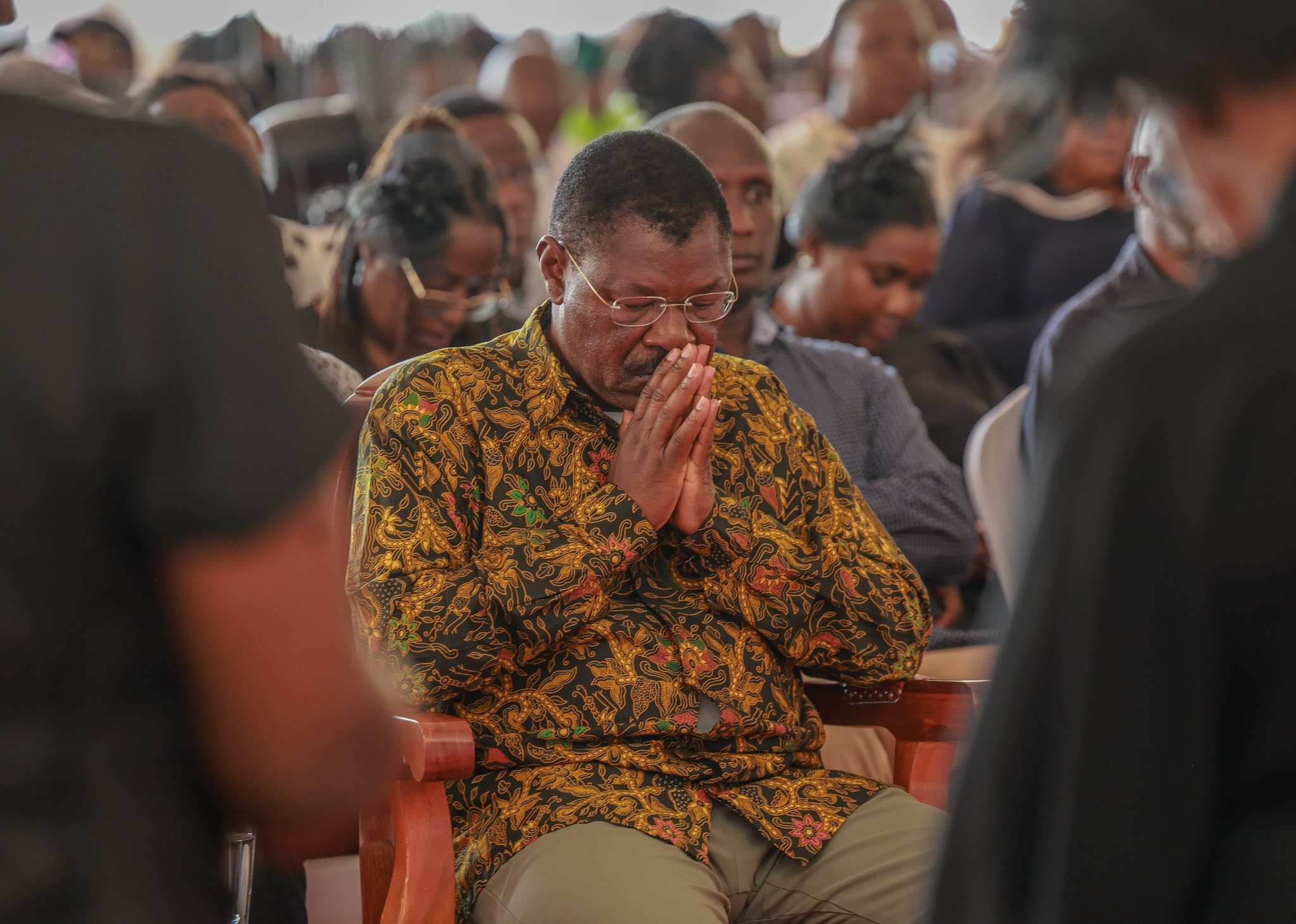

The EAC military chiefs met on June 19, 2022 to discuss and finalize the deployment, while the presidents met in Nairobi on June 20, 2022 in the absence of Tanzania's Samia Suluhu Hassan.

Anxieties and tension in the meeting were evident as Rwanda President Paul Kagame and his DRC counterpart Félix Tshisekedi hadn't met since the latter rose to power in 2019. The anxieties between Kigali and Kinshasa date back to 1994 Rwanda genocide.

The EAC member states agreed to deploy EASF toDRC, along with Uganda and Rwandese borders, to fight the militia in Ituri, north of Lake Kivu. This comes after the increased dominance of the Tutsi-supported NSAG, the 23rd March 2009 movement or M23 revolutionary army in eastern DRC.

The M23 has received support from other different militia groups, such as the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR), Burundi’s National Forces of Liberation (FNL), and Uganda’s Allied Democratic Forces (ADF).

The formation of the M23 group, and the reason the movement has sympathy from the Rwandese administration can be understood from the mid-1990s Congolese conflict, the tension between Kinshasa and Kigali, and the Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Front campaign to fight the Hutu-led NSAGs since the genocide of 1994, which spread to the DRC borders in 1996.

M23 is dominated by the Tutsi ethnic group fighting the DRC army, claiming historical betrayals from the Kinshasa regime, and this Tutsi-led NSAG also claims to fight the Hutu-founded NSAGs who escaped after the 1994 Rwanda genocide.

The RPF, together with the Burundi army, coalesced with Laurent-Désiré Kabila’s Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation (AFDL) and Angola, defeating Mobutu Sese Seko wa Za Banga in 1997.

The neighboring countries of Uganda, Rwanda, Angola and Burundi support helped Kabila to gain power and territories in North and Southern DRC. However, President Kabila betrayed them after getting to power.

Later in 1998, the anti-Kabila Congolese Tutsi, gaining support from Rwanda and Uganda, formed the Congolese Rally for Democracy (RCD) NSAG along the DRC-Rwanda borders north of Lake Kivu in the Goma region. Both Yoweri Museveni and Kagame’s administrations have been accused of illegal extraction activities by the international community and United Nations along with eastern DRC. And Kigali administration has been accused by its Kinshasa counterpart and the United Nations Security Council of being loyal and supportive to the Tutsi-dominated M23.

The call for the deployment of the EASF by President Kenyatta raises questions about the hidden intention of such joint forces because the relationship between corruption allegations and war is not new.

The Kenyan Defense Forces under the African Mission in Somalia (Amisom) has been accused of smuggling charcoal and sugar from the port of Kismayo.

Additionally, NSAGs in eastern DRC control mines and transit routes with the exchange of arms and weapons, while Rwanda, Uganda, and Kenya act as transit routes and mineral refiners of the extracted minerals from Ituri and North Kivu. Thus, with the rich resources such as coal, iron-ore, tantalum, tungsten, tin, and gold in North Eastern DRC in Ituri, the deployment of EASF corruption deals is a future possibility in the region.

Additionally, President Kenyatta’s calling for deployment validates Kenya's leadership at the UNSC as a non-permanent member. However, it means more militarisation in the eastern DRC, and military diplomacy has never been a solution to conflict.

Amisom stagnation in Somalia is an example, demonstrating dominance and territoriality among the member states. EASF only adds conflict of interest into the already militarised Ituri and Kivu regions.

History explains territoriality, dominance, and conflict of interest in eastern DRC. The M23 war and its external support escalated to the borders of Congo-Uganda along Lake Albert in the Ituri region leading to Uganda's increased involvement in the conflict from 2003.

The Ituri region was later dominated by the Ituri militia, the foreign rebels from the FDLR, FNL, and ADF. These NSAGs forces were loyal to the former DRC army general, Laurent Nkunda Batware, also a Congolese Tutsi. He was accused of supporting the NSAG dominating the north of the Kivu region, the Congolese Tutsi, and the Tutsi-dominated Kagame administration, and he later helped the NSAG in Eastern DRC along the Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi borders.

The Rwandese forces later arrested Nkunda to amend the destroyed relationship between Kigali and Kinshasa administration. However, the Kampala and Kigali administrations have been accused by various international organisations of supporting the NSAG, which later became M23 along the Ituri and Lake Kivu region.

Nkunda helped the Rwanda Patriotic Front fight against the Hutu-dominated Rwandan Army Forces in the 1994 Rwandese genocide. He later created an NSAG group by the name The National Congress for the Defense of the People (CNDP), a movement that recruited in Rwanda, Burundi and north of Kivu. It fought the DRC army but later defeated in 2009, when Nkunda was arrested, and Bosco Ntaganda, who was Nkunda’s chief of staff and a member of CNDP took the leadership from Nkunda.

Later, on March 23, 2009, the DRC government and CNDP NSAG signed a peace agreement but it failed in 2012. M23 was thus formed in reflection of the failure of the March 2009 peace deal.

The unrest in the eastern Congo and the western Uganda borders led to Kampala peace talks led by President Museveni's leadership. The Kampala talks led to the Nairobi declaration on December 12, 2013.

The declaration stipulated that M23 transform into a political party, which failed after about 300 CNDP soldiers rebelled from the peace deal in 2014. And on January 30, 2014, the UNSC resolution 2136 called for an arms embargo, the end of M23, condemning the NSAG's internal and external supporters, including the flow of weapons into DRC.

The dominance of the Tutsi ethnic group in the M23 demonstrates the soft spot of the Kigali administration. However, the Kagame administration denies such allegations of supporting the NSAG, creating an antagonistic relationship between the Kinshasa and Kigali administrations.

Additionally, the Nairobi administration's call for the deployment of the EASF in the Ituri, north eastern DRC is a move to show its leadership and position as a non-permanent member at the UNSC and attract international attention. However, it escalates diplomatic tension among the different EAC members.

The uncertainty in Uganda and the age of Museveni demonstrates that the newly elected Nairobi administration’s leadership in the August 2022 polls is critical to the EAC and its deployment of EASF in the Eastern DRC.

Without good leadership, the EAC could create further diplomatic tension between Kigali and Kinshasa, and the security of North Kivu and Ituri is uncertain.

Okwany is a research fellow at the Department of Political Science and Public Administration, the University of Nairobi.

Atieno is a research fellow at Bonn International Center for Conflict studies. Email: [email protected]

WATCH: The latest videos from the Star