Few public policy ideas in Africa command such universal agreement yet show such uneven progress as Universal Health Coverage.

The principle is simple: every person should be able to access quality healthcare without facing financial ruin. It is written into Kenya’s constitution and echoed in successive national plans.

Yet the distance between what is pledged and what is delivered remains wide.

Aspiration is the vision of what ought to be: a world guided by fairness, equity and shared opportunity. Realisation is what happens when that vision is tested against capacity, cost and time.

Between the two lies the space where most national ambitions stall: the difficult work of translating moral clarity into operational coherence.

Kenya’s journey toward UHC captures this perfectly, a

policy that has long been admired, debated and promised, but rarely executed

with the discipline needed to make it real.

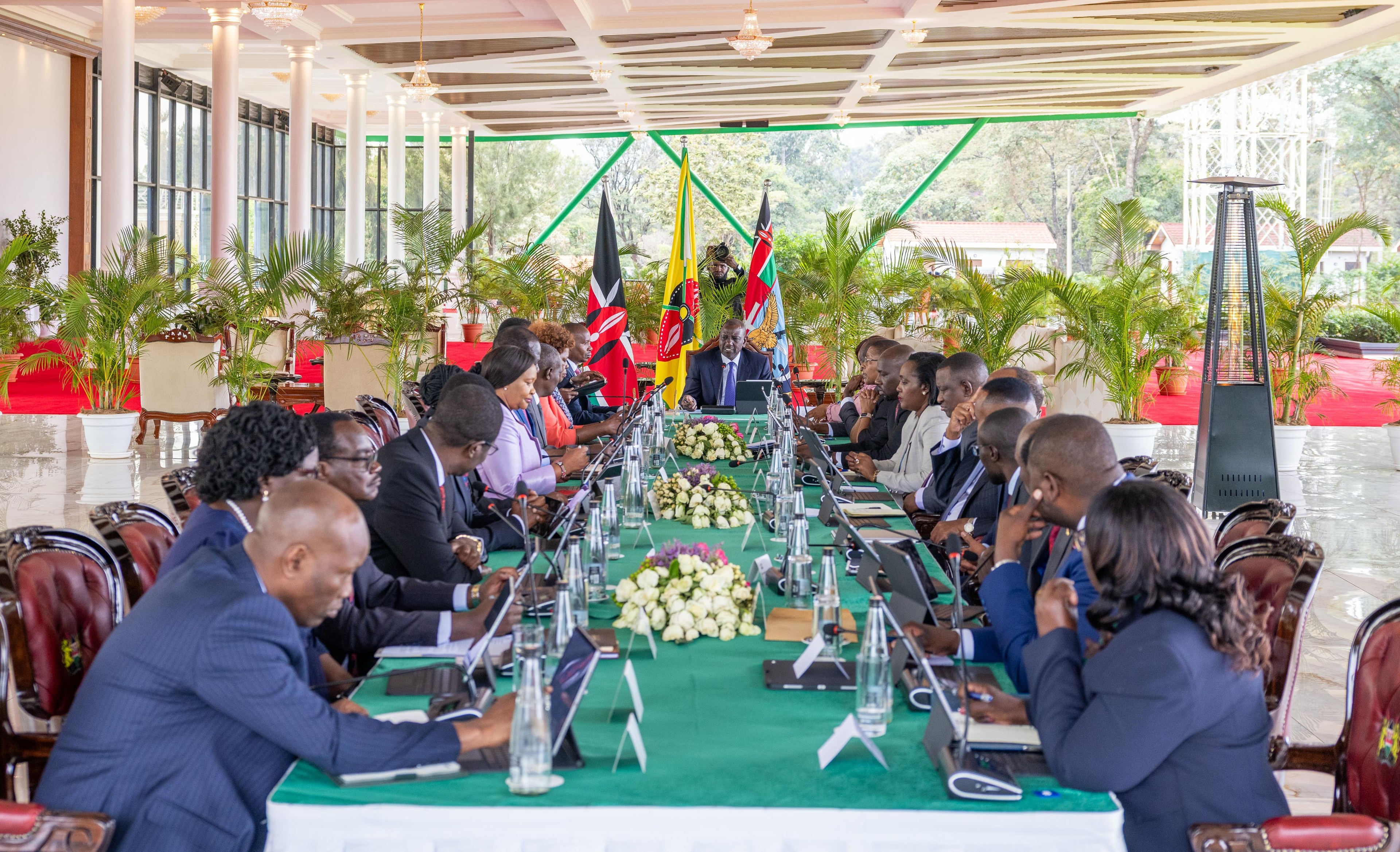

Over the years, successive administrations have launched pilots, created funds and restructured agencies in pursuit of the goal.

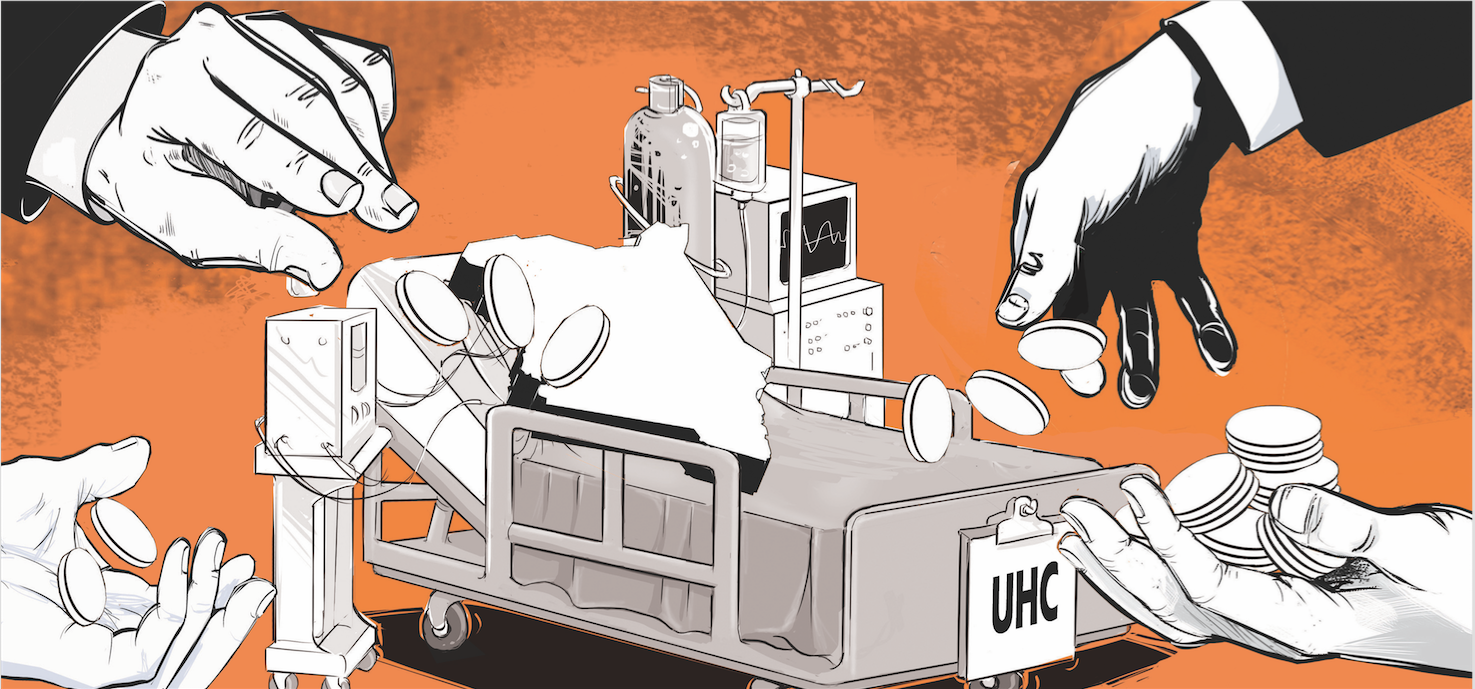

Yet the lived experience of ordinary citizens tells a different story. County hospitals continue to face drug stockouts, staff shortages and delayed reimbursements.

Patients still pay

out of pocket for care that is supposed to be covered, and many remain

uninsured altogether. Financing, service delivery and accountability continue

to move on separate tracks, occasionally intersecting but seldom reinforcing

each other.

The numbers underline the problem. Out-of-pocket spending still accounts for nearly 40 per cent of Kenya’s total health expenditure, one of the highest shares in East Africa.

Fewer than one in five Kenyans are covered by any form of health insurance. The

new Social Health Authority, established to replace the NHIF, has been

allocated about Sh6.1 billion for primary care, a fraction of what counties

estimate they need to make universal access credible. The aspiration remains

noble, but the architecture supporting it is weak.

Across sectors and across history, the same lesson emerges. Vision alone is never enough. In business, enduring firms succeed not through slogans but through systems that deliver consistently.

In politics, real reformers build institutions strong enough to outlast them. In religion, belief becomes durable only when it is reinforced by daily practice. And in science, discovery depends not on inspiration but on the discipline of repetition and proof.

Realisation in any

field rests on the same foundations: focus, integration and patience. Success

belongs to those who reduce complexity to its essence, control the process from

start to finish and sustain effort long after the initial excitement fades.

Countries that have managed to achieve genuine UHC, such as Thailand, Rwanda and Japan, did so through this kind of persistence.

They avoided the temptation to multiply schemes and instead consolidated them. They built reliable financing systems, invested in local delivery capacity and measured results with an almost obsessive regularity.

Their progress shows that the gap between aspiration and

realisation is not about ideology or even resources, but about administrative

discipline and policy continuity.

Kenya’s difficulty lies not in ambition but in fragmentation. Policy shifts outpace institutional design, new agencies are created faster than old ones are evaluated and announcements are mistaken for outcomes.

The rhetoric of universality

repeatedly collides with the arithmetic of budgets and the politics of short

cycles. Financing, procurement, and human resources remain locked in silos,

each answerable to its own bureaucracy rather than to citizens. Until these

components operate as parts of one design, reform will remain reactive and inconsistent.

Vision without execution is wishful thinking, and execution without vision is bureaucracy. Universal Health Coverage demands both.

The next phase of reform must shift from proliferation to coherence, from the politics of expansion to the discipline of alignment.

Resources should be concentrated on a few essential benefits that can be delivered completely and reliably. Financing, supply chains and workforce management must be coordinated within a single accountable framework.

Progress should be measured not by budgets spent or facilities opened, but by

tangible improvements that citizens can feel: medicines in stock, staff

present, care delivered.

Universal Health Coverage will not be won through declarations but through detail. Its success will depend on whether Kenya can connect design to delivery, how money flows, how care is provided and who takes responsibility when it fails.

If those

lines remain disconnected, UHC will continue as a political promise that never

matures into practice. But if they are joined with consistency and discipline,

it could become Kenya’s most important governance reform, evidence that a

nation known for vision can also master execution.

Surgeon, writer and advocate of healthcare reform and leadership in Africa