Concerns are emerging that media coverage and framing of religious extremism in Kenya, by focusing narrowly on security aspects rather than the broader push and pull factors, are limiting the handling of the issue to a security lens only.

Unlike the broader fight against terrorism, violent extremism, and radicalization, where the government has applied a multi-agency approach incorporating social, cultural, and economic considerations, media analysis suggests that once security agencies move in, arrest, and charge leaders of controversial sects, the matter is deemed resolved.

However, the opposite appears true. More sects are emerging, and their ideologies demand wider, multidimensional interventions.

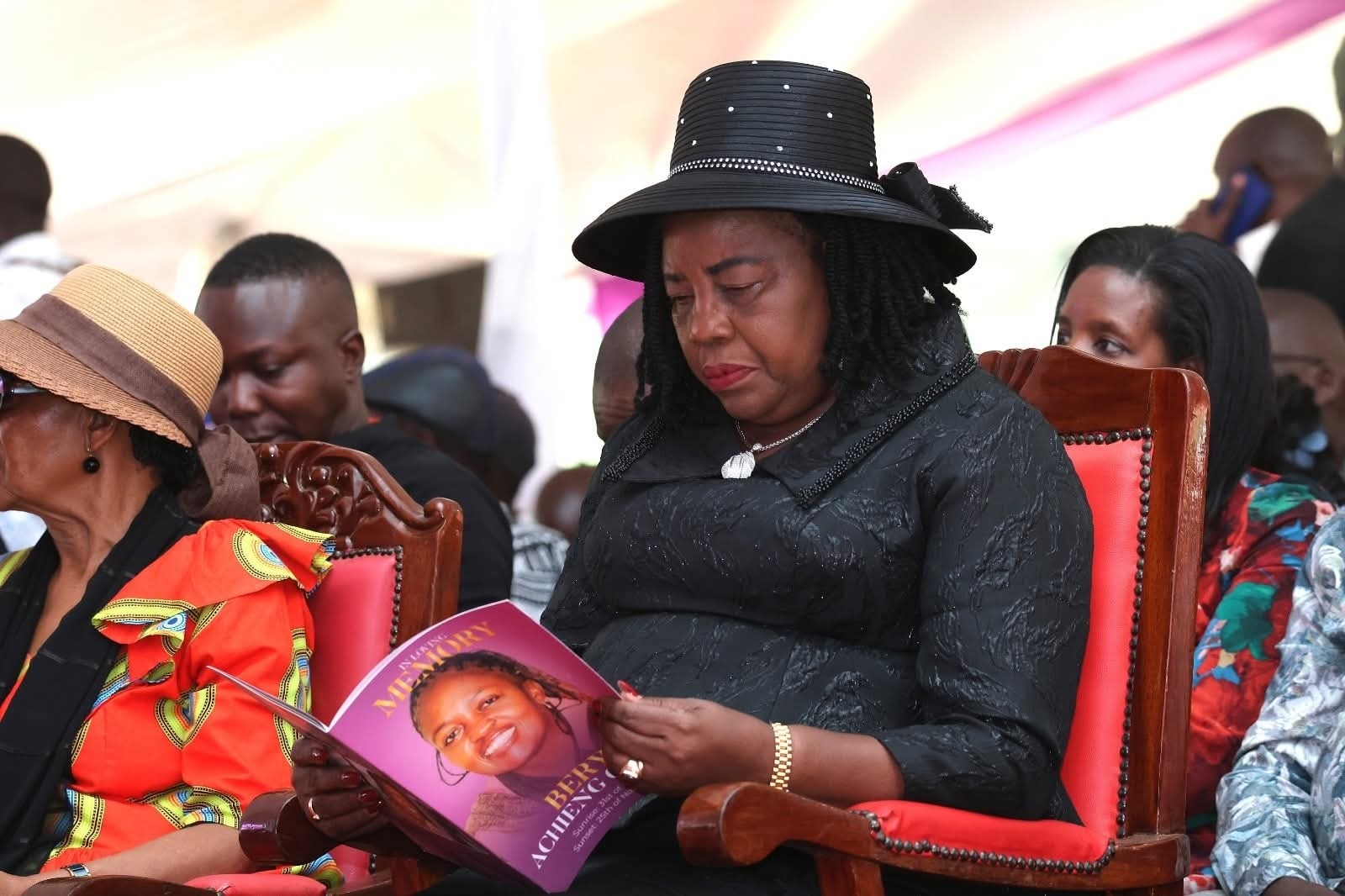

For example, coverage of the Good News International Church in Shakahola, Kilifi County, has been largely episodic. Reports often highlight the dramatic and near-heroic portrayals of the sect’s leaders, focusing on their controversial teachings and influence.

Yet, there is limited examination of the underlying social, economic, and psychological factors that drive followers to such movements.

Similar concerns have been raised regarding the activities of the unregistered Kabonokia Sect, which operates in parts of the country. The sect targets economically disadvantaged, illiterate, and marginalized individuals, discouraging them from seeking conventional medical care or formal education.

Despite the growing incidence of religious extremism, the associated socio-economic drivers pushing people into such sects have not been adequately or professionally framed in the media. Coverage often centers on the founders, portraying them as isolated criminal cases rather than symptoms of deeper systemic issues.

Media reports on the Shakahola tragedy have primarily focused on security lapses and intelligence failures, resulting in an almost exclusively security-oriented response, arresting leaders, restricting access to sites, and establishing task forces.

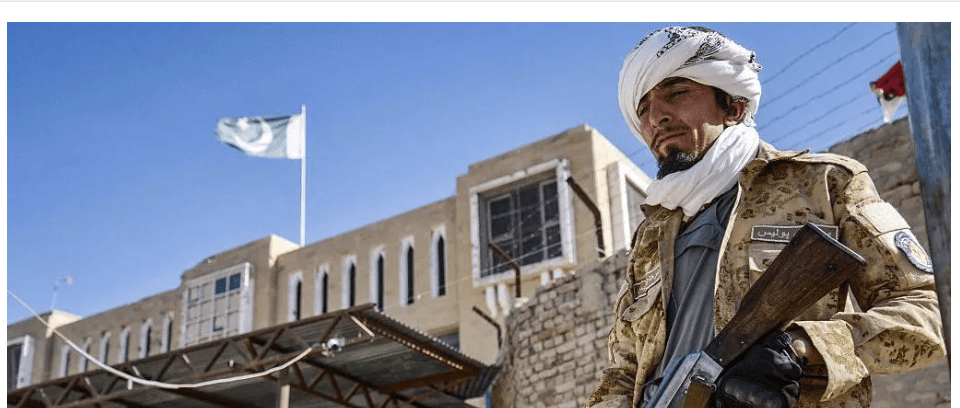

This contrasts sharply with earlier countering violent extremism (CVE) efforts, where interventions acknowledged broader root causes such as poverty, marginalization, illiteracy, and political exclusion. Those initiatives brought together various stakeholders, including government agencies, non-state actors, and the media.

Security operations were enhanced to improve intelligence gathering, communities were supported to build resilience through rehabilitation and reintegration programs, and dialogues were held between security actors and journalists to ensure responsible reporting that did not compromise national security.

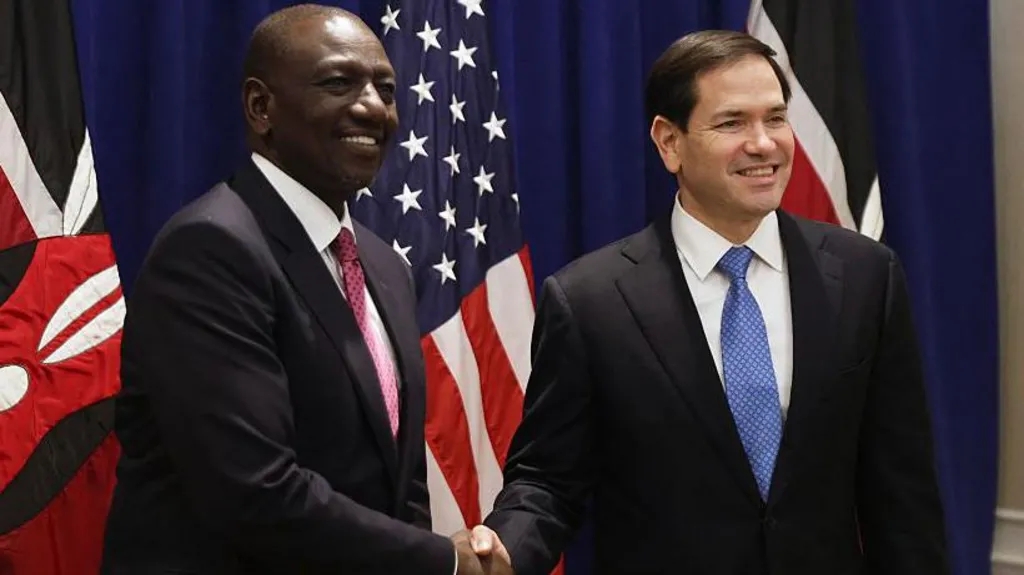

The National Counter Terrorism Centre (NCTC) has been instrumental in coordinating such efforts across government. The Media Council of Kenya (MCK) has also partnered with the Ministry of Interior to hold media-security dialogues and produce guidelines on reporting terrorism responsibly.

Today, however, in the context of religious sects, the broader causes are not being sufficiently highlighted to inform serious policy interventions. With media coverage often reactive and event-driven, religious extremism continues to be treated primarily as a security concern.

For instance, among the recommendations of the Shakahola Task Force appointed by the President was the need to raise public awareness, promote religious tolerance, counter violent extremism, and regulate harmful religious content in digital and broadcast media.

Similarly, the Senate Ad-Hoc Committee on Shakahola called for regulating digital platforms by engaging social media companies to de-platform Paul Mackenzie and prohibit related extremist content. The Kenya National Commission on Human Rights (KNCHR) has also recommended early interventions by regulatory bodies to prevent misuse of media freedoms by extremist preachers.

The media’s role has come under scrutiny because, while it serves to inform and shape public opinion, it also possesses the power to frame narratives and, in some cases, distort public understanding by presenting a partial version of events as the whole truth.

While the media plays a vital role in supporting democracy, it can also become destructive when it fails to provide comprehensive, balanced coverage. Instead of exploring the wider context of social trends, it may frame events narrowly and amplify sensational elements.

It is therefore crucial that the media be fully integrated into national strategies addressing terrorism and violent extremism. Journalists often face physical risks during security operations, exposure to traumatic scenes, or potential targeting by both terrorists and security forces.

There is also the risk of radicalization or manipulation through disinformation. Targeted support and training for journalists are essential, as they remain a high-risk group in the broader war on extremism.

The Media Council of Kenya’s Revised Code of Conduct for the Practice of Journalism (2025), Section 24, underscores responsible coverage of religion. It states: “Do not use religious content to maliciously attack, insult, harass, or ridicule other faiths, sects, or denominations or their adherents. Avoid glamorizing occultism, witchcraft, exorcism, paranormal activities, or pseudo-scientific practices. Ensure that religious content featuring superstitious or pseudo-scientific beliefs and practices is presented responsibly, in a manner that does not mislead the public or contravene this code.”