The question came quietly, like a scalpel sliding between

ribs.

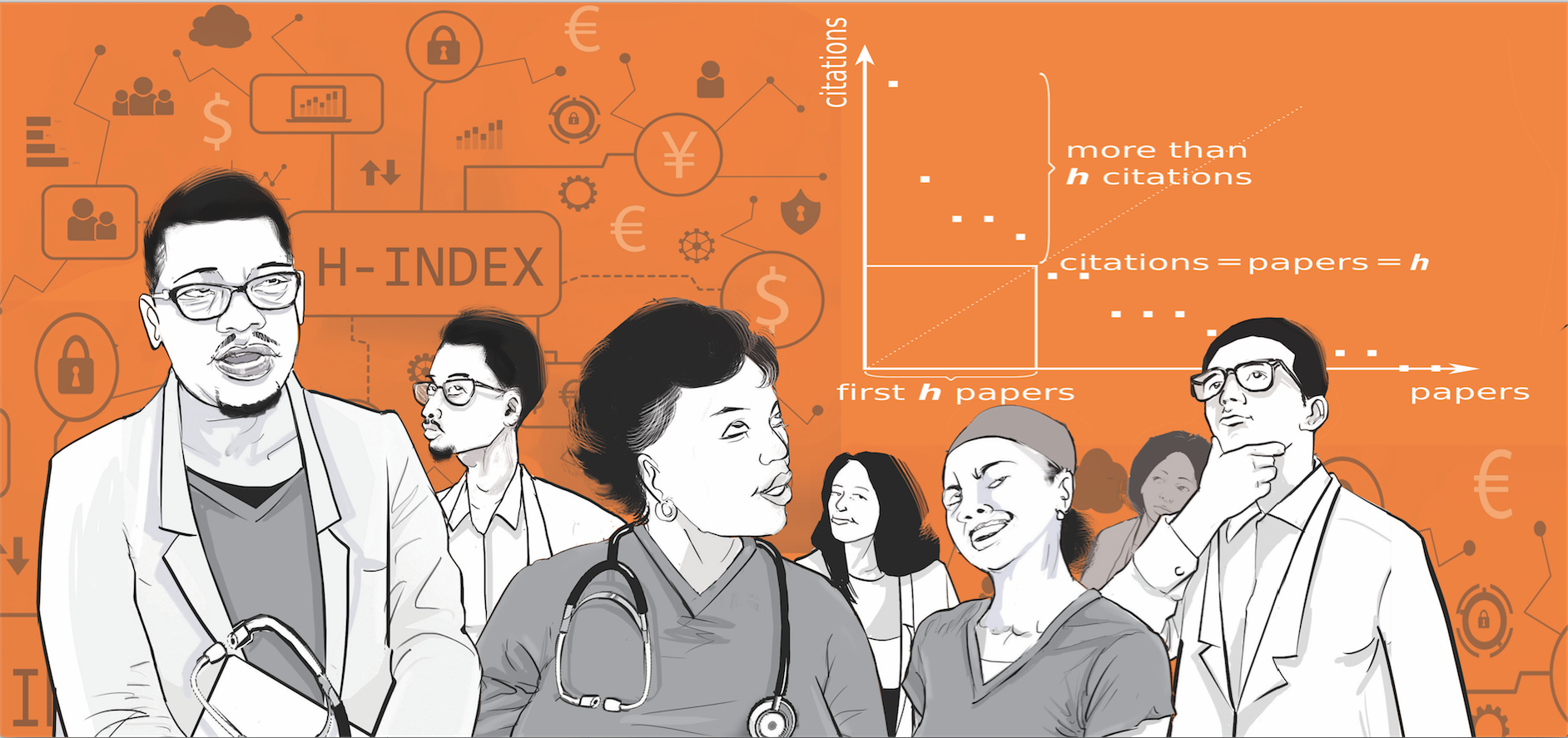

“What is your H-index?”

I had been speaking about systems re-engineered, teams

rebuilt and patients who could now walk again. Three companies were founded. Forty

livelihoods sustained. A public hospital department was reshaped into a modern,

self-running service. The only orthopaedic oncology unit in East Africa was built

from the ground up.

Then, in one sentence, it all collapsed into a number.

How many times had other scholars mentioned my name in their

footnotes? That, apparently, was the currency of my worth. Not the policies

influenced or the mothers and fathers who could now access care, but citations.

In that moment, I realised something unsettling: science has

created a false economy.

The H-index was meant as a blunt but helpful tool, a way to

gauge productivity and influence. The metric has since become a kind of

passport in science—used from Boston to Beijing, Nairobi to New Delhi. Yet its

universality is mostly procedural, not philosophical. It works best in citation-heavy

fields like physics or biomedicine, and falters in disciplines where knowledge

is built through teaching, systems or art rather than journal papers.

In the humanities, where books shape generations, the H-index barely registers. In clinical practice, where a single innovation can save hundreds of lives but yield few citations, it misses the point entirely.

It is everywhere, but it does not mean the same thing everywhere. Somewhere

along the way, it became a universal badge of legitimacy. Committees cling to

it. Donors nod to it. Universities trade on it.

But like any inflated currency, it distorts the marketplace.

It rewards visibility within the ivory tower, not impact beyond it. It tells

young scientists that prestige comes not from discovery but from being

referenced by the right people in the right journals.

And so the incentives twist: papers over patients, citations

over cures, bibliographies over breakthroughs. Ask a mother in a rural clinic

how many times her doctor’s name appears in PubMed, and she will look at you

blankly. Her currency is survival. Her only metric is whether she and her child

make it through the night.

Science does not need to abandon its metrics; it needs to

rebalance its portfolio. The H-index measures intellectual echo, but we need a

parallel measure for human impact.

An Impact Index, perhaps, one that asks: What systems have

you built that endure? How many people have you trained, mentored or inspired?

What knowledge have you translated into policy, practice or product? How much

access have you expanded for those left behind? What real value has your

science created for society?

These are not soft questions. They are the hard accounting

of progress, the kind that decides whether knowledge lives in journals or in

people’s lives.

Rwanda offers a masterclass in this recalibration. Dr Sabin

Nsanzimana, its Minister of Health, says if you want to judge a health system,

look at two numbers: maternal and child mortality. Over 25 years, both have

plummeted.

In 2024, Rwanda stopped a Marburg outbreak before it could

spread. In 2025, TIME named Nsanzimana among its 100 Next leaders, not for his

H-index but for outcomes: women who lived through childbirth, children who

lived through childhood, futures secured.

History repeats this truth. The world remembers not who was

most cited, but who was most consequential.

Albert Einstein received his Nobel not for relativity but for the photoelectric effect, a discovery that powered modern electronics. Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman were once dismissed for pursuing mRNA.

Their

reward came not in early citations but in vaccines that saved millions. Norman

Borlaug, no bibliometric star, won the Peace Prize for sparking the Green

Revolution, a quiet revolution that ended famines.

Citations follow consequence, but consequence begins with

courage.

From my vantage point, half in the clinic and half in the

boardroom, I see the same disease in both science and business: valuation

error. When markets price visibility over value, bubbles form and burst. When

academia prizes citations over solutions, the same happens: reputations

inflate, relevance deflates.

The purpose of science was never to be cited; it was to be

useful. To light up dark rooms, to heal, to feed, to build. If innovation is

the research dividend, then human welfare is the return on investment.

No one erects statues for citation counts. No one gathers their grandchildren to tell stories about impact factors. What endures are the systems built, the minds opened, the lives touched. What endures is science that bends toward service, not self-congratulation.

If we continue rewarding the wrong currency, science may enrich its elite while bankrupting its purpose. But if we recalibrate, if we begin to prize the builders, the doers, the transformers, then science can reclaim its rightful role: not as a marketplace of citations but as a covenant with humanity.

Because the true index of impact will never be written in footnotes. It will be written in lives.

Surgeon, writer and advocate of healthcare reform and leadership in Africa