Over the last 10 years or so, if you worked for a newspaper, then sooner or later someone well known to you would have said these dismissive words to you: “I don’t know why you people bother publishing that newspaper.

I get all my news from social media.” And there seemed to be much to support this view. By the time the earliest deliveries of the daily newspapers were made in the morning (say, at 5 am), most of what was in the significant headlines would already have been read by the diligent social media devotee on the previous evening.

And though it’s the newspapers which arguably have the best informed and most experienced commentators, there are – all the same – dozens of recently retrenched or otherwise unemployed professional journalists who have opted to go freelance. And their newsletters or (more often) podcasts, are in no way inferior to what you get from the mainstream media. But something strange happened on the road to mainstream media obsolescence.

The age of artificial intelligence came upon us. And with that, everything changed. The tragic events arising from the recent Saba Saba demonstrations illustrate this changed reality very well.

There can hardly be a Kenyan who owns a smartphone who did not constantly wonder which of the many posters, video clips, and ‘Breaking News’ announcements were actually valid news items, and which ones were artificially generated by some AI software. One might ask for example, “Was that burning building really in the Nairobi CBD, or was the image taken from the ongoing atrocities in Gaza? Indeed, was the building in that video burning at all, or just made to appear to do so?”

Also, a few years ago, when Ugandan youth leader Bobi Wine challenged long-serving President Yoweri Museveni in the presidential election, the Ugandan security forces used water cannon vehicles on Bobi Wine’s supporters, spraying dyed water (reportedly to facilitate later identification of the demonstrators) far more liberally than is usually the case in Kenya.

As the average Ugandan looks very much like the average Kenyan, and the average Ugandan street is very much like the average Kenyan street, some of the images of police using water cannons against the Saba Saba demonstrators could just as easily have been cropped from Ugandan TV footage.

In other words, those who had come to believe that in social media they had found a viable alternative to local newspapers and TV stations, are now having to think again. Basically, they are gradually realising that a news organisation, structured as a private-sector corporation and staffed with dozens of professional journalists, is a very different thing from a solo tech-savvy blogger-for-hire who can create and disseminate just about any headline you may want, provided you pay him. Which is not to say that a newspaper’s editorial team may not slant the ‘interpretation’ of the news in a given direction.

This may happen, especially in their choice of words for the headline of any given news report. But they would never knowingly publish news that they knew very well to be false, much less invent news headlines as some bloggers will do (and with great expertise that fools many viewers or readers). And I might also add here that newspaper sales, all over the world, are increasingly tied more to the quality of commentary, analysis, and other unique offerings in the inside pages, than breaking news headlines.

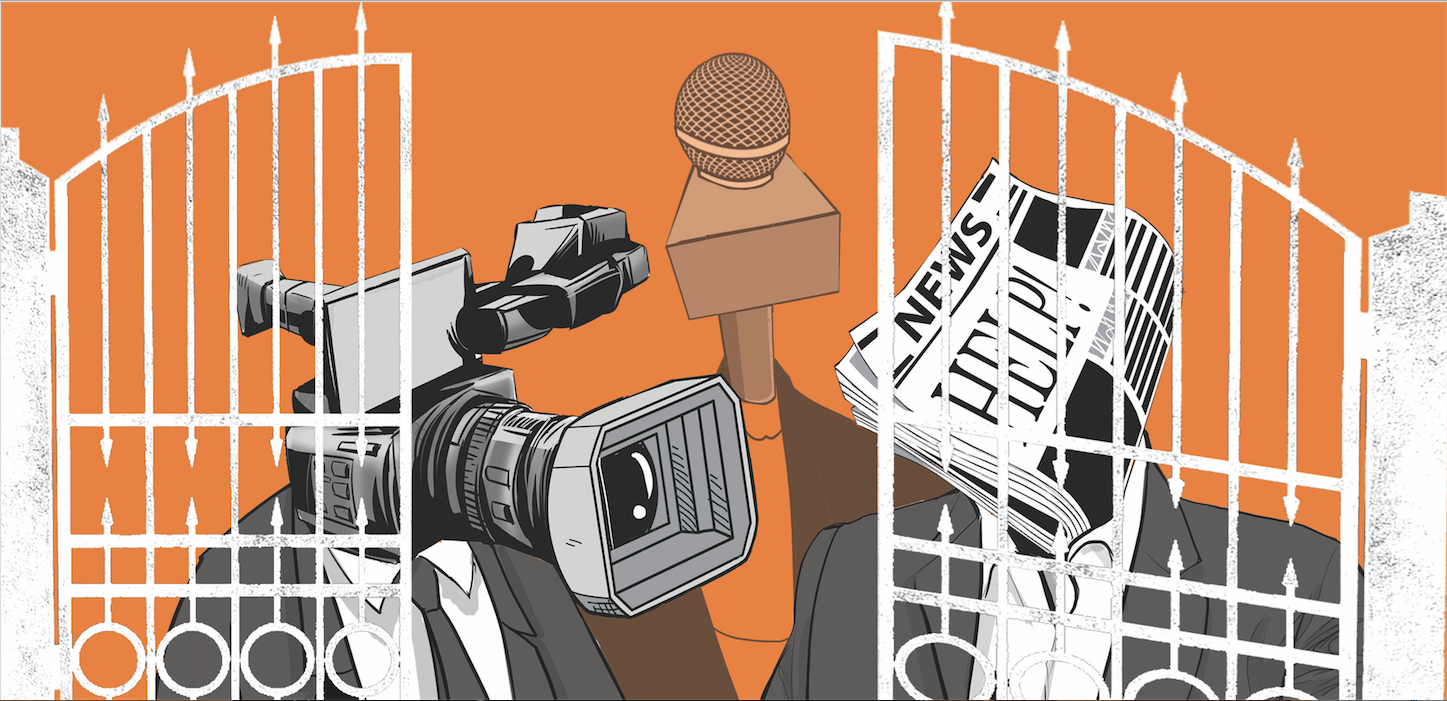

All in all, we seem to be heading back to the days when accredited media gatekeepers – professional journalists and editors whose job it is to decide what to publish and what to leave out of their newspapers – have an important role to play in determining what news gets into circulation and potentially influences the public.

When the news consumer who proudly “gets all their news from social media” comes across some alarming or dramatic news item, they will have no choice but to check and see if any mainstream media outlet also has the same news item on its website.

For if they do not, then the social media-dependent consumer will have to assume that this is just mischief put up by someone with serious AI skills who had an agenda to push and very likely the event described did not actually take place. And is it not ironic that, after months of being told that we in the media would soon lose our jobs to AI programmes, it now turns out that it is the advance of such AI software that has made professional journalists indispensable.

Wycliffe Muga is a columnist