Here we go again.

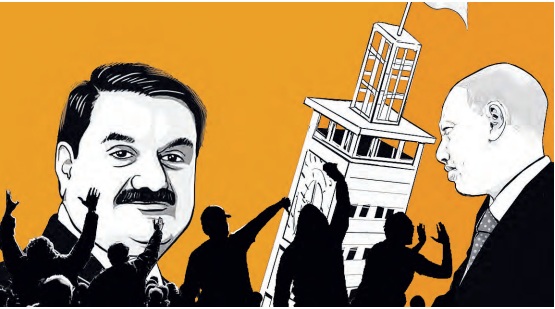

After months of ignoring credible warnings (some of which I raised in this very column) President William Ruto last week abruptly backtracked on Kenya’s dealings with the controversial Adani Group.

Citing “new information provided by our investigative agencies and partner nations,” Ruto announced that the Indian company would no longer be involved in Ketraco’s power supply plans nor the mooted JKIA facelift.

Ruto’s U-turn came less than 24 hours after the US Attorney’s Office in the Eastern District of New York unsealed a blockbuster indictment targeting the Adani Group.

The charges allege that senior Adani executives, including Gautam Adani himself, paid $250 million (Sh32.4 billion) in bribes to secure solar energy contracts in India.

Given the track record of New York prosecutors, Adani’s goose appears cooked.

The question on the minds of many Kenyans, however, is this one: how did a country whose leaders incessantly preach anti-corruption end up courting such a conspicuously corrupt entity?

The bitter truth is that Kenya has long specialised in ignoring glaring red flags when getting into bed with dubious characters.

For example, in the aftermath of the 2013 election, the UK’s Serious Fraud Office (SFO) prosecuted British businessmen Nicholas and Christopher Smith for bribing officials of Kenya’s Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission to win ballot paper printing contracts.

Despite clear evidence, Kenya failed to lift a finger to bring Its implicated officials to book.

Similarly, in the 1990s, former Energy minister Chris Okemo and Kenya Power CEO Samuel Gichuru allegedly laundered nearly $10 million (Sh1.3 billion) in bribes through Jersey-based accounts.

When the island of Jersey sought their extradition years later, Kenyan authorities very publicly refused to cooperate and actively shielded them from prosecution despite overwhelming evidence.

What do these examples teach us?

Mainly that the truth about what ails the nation is staring us in the face. Institutions tasked with ending impunity have been paralysed by political interference and a sheer lack of will.

The result is institutional atrophy.

That’s why accountability now mostly depends on foreign courts rather than our systems.

As a member of the Senate, I have personally investigated the Adani issue.

I have pleaded with Cabinet secretaries for transport and energy to exercise caution.

I was shocked to learn that due diligence on Adani was conducted by Ketraco staff rather than an independent body.

As we all know, the risk of internal teams being compromised is glaringly obvious.

When citizens protested against the Finance Bill, 2024 and, later, the Adani deals, Parliament largely fell in line with the Executive.

Only when the President reversed course did we as representatives clap furiously, belatedly pretending to have championed the right outcome all along.

Such hypocrisy betrays the essence of representation as codified in our constitution.

We are meant to serve as instruments of the people’s will, not as rubber stamps or mere enablers of the Executive’s agenda.

And yes, I count myself among those who must remember this solemn duty.

Kenyans have shown a vigilance and consistency that surpasses that of their elected representatives.

Armed mostly with social media tools, our fellow citizens are shining a bright light on corruption and demanding better governance.

Indeed, if not for whistleblowers like Nelson Amenya and the vigilance of ordinary Kenyans, the Adani deals might have quietly proceeded.

Parliament cannot afford this level of inertia.

My colleagues and I have to approach public service with a keen sensitivity to public sentiment.

In this regard, we have to tighten the transition to the Social Health Authority, which was recently rebranded as Taifa Care by the President.

As a member of the Senate’s Health committee, I am baffled that we would overhaul a critical system without thorough testing.

It’s time my colleagues and I returned to the fundamentals of our mandate as representatives.

If we cannot hold the Executive accountable, ensure due diligence, or protect the public interest, then we must accept the inevitable; the people will reclaim the power the Constitution entrusted to us.

History has shown (and I have certainly seen enough in the last few months to believe that it is true) that when leaders fail to rise to the moment, the people will.

Author is the minority whip of the Senate and senator of Narok County