There is a question that will invariably come up when a journalist who has attained a degree of name recognition is chatting with people who don’t know him particularly well.

That question is, “Why don’t you run for a parliamentary seat?”

The basis of this question is that even a journalist who is not particularly famous will often have his name published in the newspaper he works for (what in the business we call his “byline”) far more often than the MP for the constituency where he has his “ancestral village.”

And this tends to make a powerful impression.

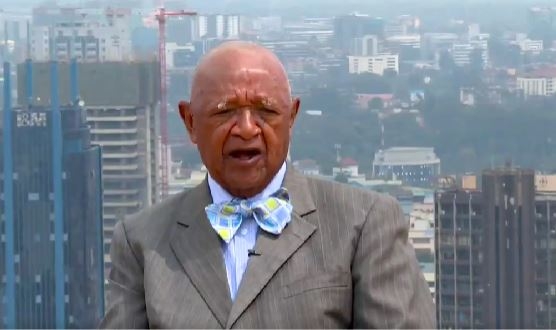

To illustrate this point, I would give my own example: I occupy roughly half a page in this newspaper every week. That is far more than any MP can hope for (unless he or she is also a weekly columnist in a national newspaper). And indeed, even most Cabinet secretaries could hardly dream of having that much coverage every week.

And yet the fact is that such an elevated media presence cannot easily translate into a successful political career. Indeed, of all the media professionals I know who have ventured into politics, I can only think of three or four who have actually been elected. The great majority have not been successful.

I believe there are three main reasons for this.

First is that Kenyan politics is increasingly about money. The electorate, quite literally, expects you to pay them to vote for you. And despite the rumours you may hear of just how well paid certain “media celebrities” are, the reality is that most media-related jobs do not pay that much.

Given these circumstances, a journalist has no chance if competing with, say, a “tenderpreneur” who has spent the previous few years scooping up public funds by the bucketful, at some ministry or other. The voters will not care where the money came from, provided they get “their share” of it, either directly in hand or as a magnificent contribution at some local fundraising event.

But an even more significant factor is that the incentive structures for success in journalism are the very opposite of the incentives for success in politics.

In journalism, what the public will in general reward with their attention (which attention translates into newspaper circulation and TV and radio ratings, and hence to advertising revenues) is the truth. In journalism, you learn very early that honesty pays. Nobody buys a newspaper to read reports that are deliberately crafted to mislead.

That is why in all the 24 years of the Daniel Moi authoritarian regime, his government was never successful in its many attempts to create its own print media “mouthpiece”. Basically, few were willing to pay for access to government propaganda.

But when it comes to politics, subtle misrepresentations as well as outright lies, work very well. To put it simply, in a country like Kenya, you cannot hope to succeed in politics if all you do is to remind potential voters of the strict budgetary limits that make it impossible to do all that much within a five-year election cycle. To succeed, you must first of all dismiss what your rival has done as being utterly inconsequential. And then proceed to tell a series of brazen lies that constitute your so-called “vision” or “manifesto.”

After a career in which you diligently struggled to retain your media credibility by being truthful to the public, it is not that easy to suddenly start selling fantasies about the “industrial parks” that you will build, or the thousands of jobs that will spring up overnight once you are elected.

But there is a third reason, and this applies specifically to what you may call “veteran journalists.” The kind of person who has spent not years but decades, working in the media.

The reason such a person can rarely be persuaded to even think of a subsequent career in politics is that they have seen Kenyan politics up close.

Not just the lies, but even more so the betrayals by your closest supporters and advisers; being ordered around like children by party leaders; not to mention the unavoidable compromises with one’s conscience.

It is not a pretty sight.