Any Kenyan who has had the opportunity to spend a year or two in an economically advanced foreign country will tell you that our people tend not to have a sense of proportion when it comes to matters involving foreigners. We tend to misread the signs.

Now this does not matter so much when it comes to ordinary people who may, for example, imagine that all white people are rich. Or that ambassadors from rich nations can grant scholarships and visas at will, to anybody they choose.

Little damage is done by this kind of mistaken assumption.

Here is an example to illustrate this:

Something which used to be common when I was younger, was that when a Kenyan student in Europe was about to return home after years spent abroad, they would buy a secondhand car to ship back home. And they often chose a luxury brand – a high-end German limousine, for example.

This magnificent vehicle, once landed here, was widely considered to be proof that he had not wasted his time in that rich foreign country: that he had accumulated wealth.

What many locals did not know was that, in Europe, the resale value of such luxury cars is shockingly low: more modest brands will often have better resale value. Among Europe’s middle class, there is no particular prestige attached to owning such a car. So there is limited demand for secondhand luxury cars: and far more demand for smaller, fuel-efficient models.

Finally, these secondhand cars will genuinely be as good as new because they have mostly been driven on excellent roads, and for just a few years; and so in Kenya they would appear no different from brand-new cars.

In other words, incidental factors specific to the European car market may allow a returning student who really does not have that much money, to drive around in a car which here in Kenya, we consider to be only affordable if you are seriously rich.

Such misconceptions are trivial enough. But they serve to illustrate how easy it is to misunderstand matters involving foreigners and foreign nations. How easy it is to misinterpret the real significance of “what you are actually seeing with your own eyes”.

Which brings me to the key point which I wish to make here:

Many Kenyans seem to me to have misinterpreted the reasons why so many global VIPs have visited Kenya in recent months.

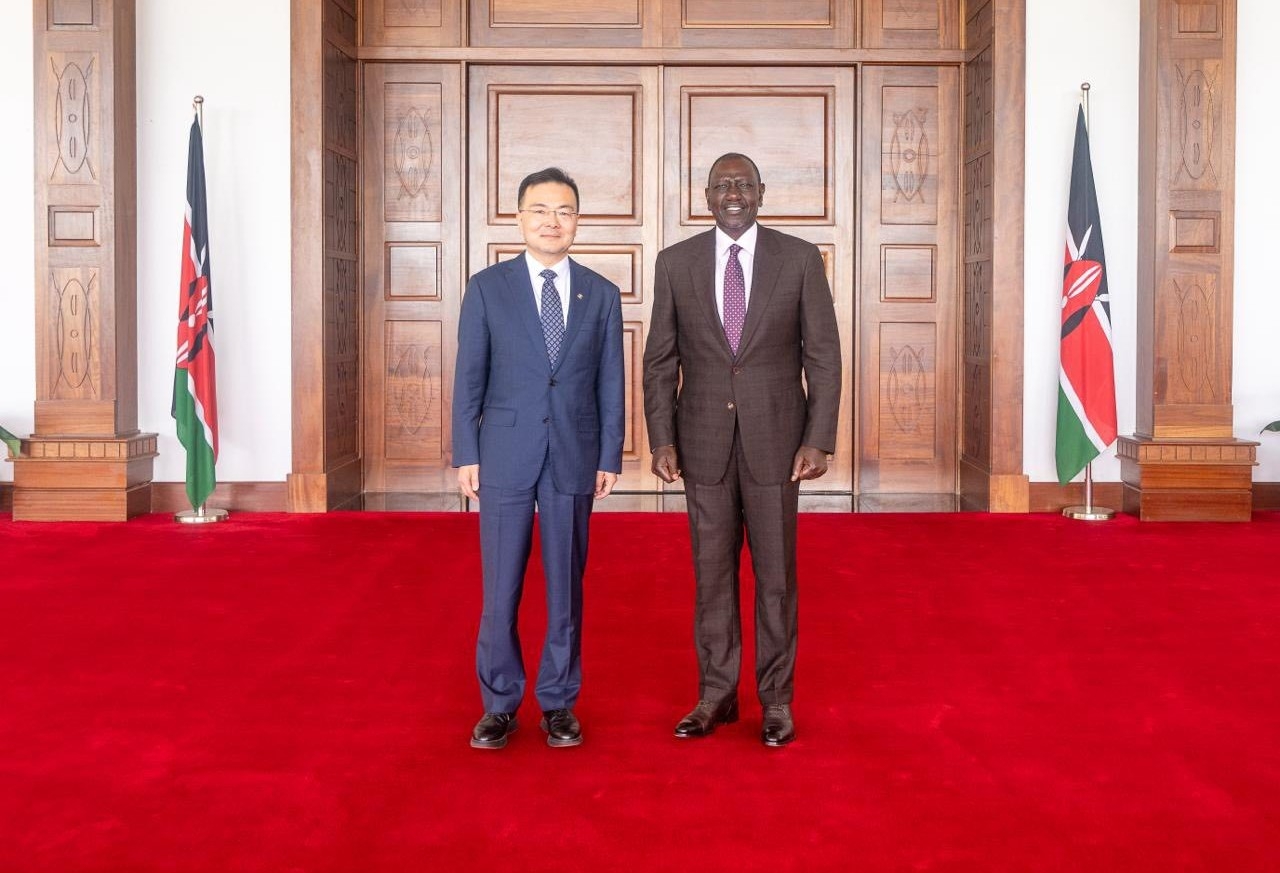

By “global VIPs” I mean people like the First Lady of the US; the International Monetary Fund managing director; the President of Italy; the President of Hungary; the Prime Minster of Japan; the Secretary General of the UN; and a few others.

Some see a sinister agenda in these visits: why all of a sudden have these otherwise very busy people been able to find time to visit Kenya? And why now? What do they really want?

Others argue that it is clear proof of the enthusiasm that influential foreigners have for the government of President William Ruto. That here at last is a proactive and energetic Kenyan president to whom they can relate.

But neither of these conclusions reveals the full picture.

I believe that all this interest in Kenya is merely incidental to global trends currently shaping up. And, as I have pointed out before, these global shifts are every bit as fundamental and transformational as those which took place during the early 1990s and led to an end to single-party authoritarian government all over sub-Saharan Africa.

Or earlier still (and in an example I have used before) we had the “winds of change” that swept through Africa in the early 1960s, and marked the end of the colonial era, and the emergence of independent African states all across the continent.

The main point is that there are, at this historic moment, renewed geopolitical rivalries generically termed the New Cold War. This development has made Africa a continent of great interest to many rich nations – to an extent far greater than was the case just a few short years ago.

We are incidental beneficiaries of the desire within the emerging rival power blocs, to make friends and influence people within Africa.