Kenya has become a frequent target of terrorist and violent extremist attacks since the al Qaeda 1998 bombing of the US embassy in Nairobi.

Between 2011 and 2015, Kenya has suffered more than 200 violent incidents involving explosives and automatic weapons linked to al Shabaab.

The attacks, targeting government and security installations, shopping centres, public transport, universities and places of worship, have left innocent people dead and hundreds of others injured, instilling fear and a sense of insecurity and exacerbating inter-religious tensions.

While the countries are struggling to address the myriad of problems presented by Covid-19, terrorist groups are having a field day in Kenya.

A stark example is northern Kenya and coastal counties, where al Shabaab attacks have persisted since 2020.

According to the Terror Attacks and Arrest Observatory of the Center for Human Rights and Policy Studies, there were 69 attacks, 122 fatalities, 42 injuries and 71 arrests from January to December.

These attacks have been happening since Kenya began sending its defence forces as part of Amisom in Somalia. Al Shabaab has increased its violent activities in Kenya, in part to force the country’s withdrawal from Somalia. The attacks have reached unprecedented levels.

In an area already destabilised by conflict, terror attacks have led to the closure of schools, breakdown of communication and paralysis of transport systems. This has affected the regions’ economies as significant resources are diverted to tackling violent extremism.

In Mandera county, 129 schools out of 295 haven’t reopened. The youth idling at home are fodder for terror groups’ recruiters. There’s zero private investment and the only source of employment, the county government, is facing serious challenges.

Terrors attacks and extremist activities have triggered geopolitical conflict in the Mandera triangle, worsening relations between Kenya and Somalia. The Mandera governor not so long ago said 50 per cent of the county is occupied by the terrorist group and accused the local security team of failing to stop the group’s attacks in the county.

The national government dismissed his remarks and accused him of playing politics with security.

As the terrorist groups have grown in strength, the national government has invested more resources to disrupt their financing and weaken their operations. In 2016, the national government launched the National Strategy for Countering Violent Extremism. In March 2017, a national task force was formed to ensure that all relevant ministries, departments and agencies undertake coordinated efforts to prevent and counter violent extremism.

Kenya’s efforts to counter violent extremism have been adversely affected by over-securitisation and limited collaboration between the community and the government. In a large study carried out in Kenya by United Nations Development Programme in 2017, 71 per cent of the respondents said government action "tipped" them into recruitment.

Stigmatisation, harassment and marginalisation by parties involved in countering violent extremism have contributed to recruitment efforts. As a result, efforts to combat terrorism often have the opposite of the intended effect.

County governments have stated that the mandate to fight violent extremism lies with the national government. Lack of collaboration and securitisation of countering violent extremism have hampered the fight against extremist groups.

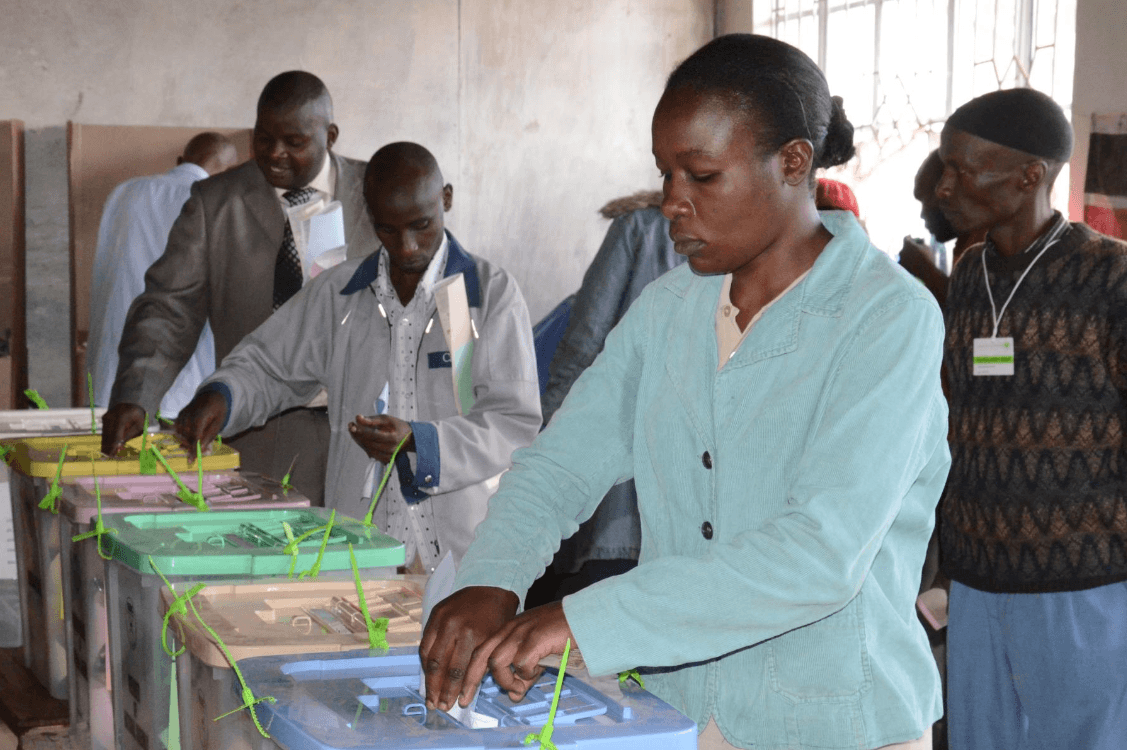

Further, the 2010 Constitution provides for democratic policing by engaging the broader community in security. To ensure seamless working between the county and national governments, the National Police Act (2011) Sec 41(9) and 97 elucidate on how the County Policing Authority operates.

The County Policy Authority is headed by a governor and is the point of interaction between the county government, citizens and national security agencies. The governor chairs the CPA with six members representing public interest. Their recommendations feed into the County Security and Intelligence Committee, an organ headed by the county commissioner, who represents the national government.

Despite being an important arm in crime and violence prevention, the CPA hasn’t taken off in the counties. The delay in the gazettement of regulations for the CPA has subsequently resulted in the delay in the release of supporting guidance and implementation of the structure in the counties.

Counter-terrorism efforts in the counties have been hampered by a lack of willingness and blame game from the two levels of government. Through the CPA, security and peace actors can explore ways to bridge the community-security gap and fight violent extremism in the counties.

P/CVE and conflict researcher

![[PHOTOS] How ODM@20 dinner went down](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcdn.radioafrica.digital%2Fimage%2F2025%2F11%2F99d04439-7d94-4ec5-8e18-899441a55b21.jpg&w=3840&q=100)