Kenya is facing a deep economic crisis, but this crisis is not accidental.

It is the result of deliberate budget choices that protect the powerful while pushing ordinary people closer to the edge.

Last week, the Kenya Human Rights Commission launched two reports, 'The Economics of Repression' and 'Who Owns Kenya?', that lay this bare. They demonstrate how public finance and land ownership have become tools of inequality. It will require considerable effort to transform them into pathways to shared prosperity.

'The Economics of Repression' focuses on public spending and debt. It shows Kenya’s budget today is structured in a way that hurts the majority, as a staggering 68 per cent of all ordinary revenue now goes to paying public debt.

In comparison, 41.8 per cent is consumed by government salaries. That leaves less than one-third of the budget for everything else, including healthcare, education, food security, water, housing, sanitation and social protection.

This imbalance did not happen overnight. In just four years, interest payments on public debt have risen from 18 per cent to 25 per cent of total government spending. Every shilling sent to creditors is a shilling taken away from hospitals, schools and social programmes. Debt has effectively become more important than people.

The consequences are severe, especially for those who rely on public support. Programmes meant to protect the most vulnerable are shrinking at precisely the moment they are needed most. Support for older persons has dropped from Sh18 billion to Sh15 billion. Funding for orphans has fallen from Sh7 billion to Sh5 billion. Resources for persons with disability continue to decline in real terms, even as the cost of living rises.

Healthcare offers another painful example. In Nairobi, home to more than 5.7 million people, real health spending has fallen from Sh8 billion to Sh7 billion. At the same time, county pending bills have ballooned to levels hundreds of times higher than total county expenditure, while wages consume nearly half of the entire budget.

Families speak of hospitals without medicine and patients turned away because they lack insurance. School learning is disrupted as the national government delays sending capitation funds.

The second report, 'Who Owns Kenya?', reveals that this economic crisis is also rooted in longstanding injustices, particularly those related to land ownership. Land remains Kenya’s most valuable resource. But its ownership is dangerously unequal. Fewer than two per cent of Kenyans own more than half of the country’s arable land, much of it acquired irregularly or held idle.

At the other end, 98 per cent of farm holdings are small, averaging just 1.2 hectares (three acres), and together occupy only 46 per cent of farmland. Meanwhile, just 0.1 per cent of landholders control 39 per cent of large-scale land. This imbalance denies millions of Kenyans livelihoods, locks young people and women out of wealth, and weakens food production.

It also

helps explain why hunger persists. Today, 2.2 million Kenyans face acute food

insecurity, and Kenya scores 25 on the Global Hunger Index, placing it in the 'serious' category.

Community land is especially exposed. Delays in registration, forged titles, manipulated boundaries and politically driven evictions continue to displace entire communities. In coastal counties like Kilifi, Kwale and Lamu, more than 65 per cent of residents lack formal land titles. Generations remain as squatters on ancestral land, and these same counties consistently perform below the national average in terms of health, education and income.

Despite land’s enormous value, land-based taxes raise less than one per cent of county revenue. Large landowners benefit from weak taxation, outdated valuation rolls, political interference and deliberate under-assessment. Prime areas, such as Karen and Muthaiga in Nairobi, and Diani, Mtwapa and Watamu on the Coast, have remained undervalued for decades, allowing the wealthy to pay a fraction of what they owe.

What emerges is a country running two economic systems. One cushions the wealthy with land, influence and low taxes. The other burdens ordinary citizens with high taxes on basic goods and income, while offering fewer and poorer public services in return.

A strong and progressive land value tax could change everything. Taxing idle and speculative land would reduce hoarding, lower prices, encourage productive use and give counties real resources. Estimates suggest that wealth taxation could raise up to Sh125 billion, almost double the current social protection budget.

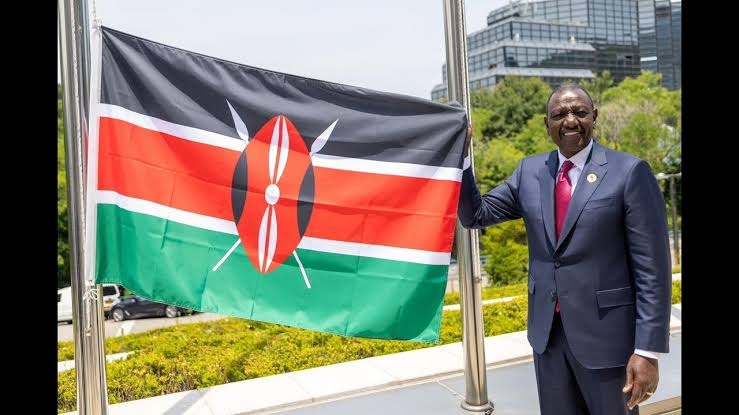

The KHRC is right to call on the William Ruto regime to rethink how Kenya raises and spends its money. That choice must change.

KHRC’s program manager for political accountability in state institutions