A comment by Jacinta Murigi, shared on LinkedIn after the death of gospel artiste Betty Bayo, captured public frustration in a few pointed lines:

“In all honesty, AAR (Hospital) should and must do better. This statement was an insult to our collective intelligence. The question was very clear, did they attend to Betty the night she was taken to their hospital in very bad shape or did they demand a deposit and hold off their critical services until the deposit was paid?

Emergency Medicine is care over formality. Stabilisation before registration. Resuscitation before questions.”

They were in response to a statement the hospital had issued about the allegations made on social media. Her words reflect genuine grief and a public yearning for clarity. But they also illustrate a deeper problem that resurfaces whenever a high-profile patient dies under unclear circumstances. The public demands full disclosure. The hospital is legally prohibited from providing it. This disconnect fuels suspicion, anger and speculation long before any formal investigation can begin.

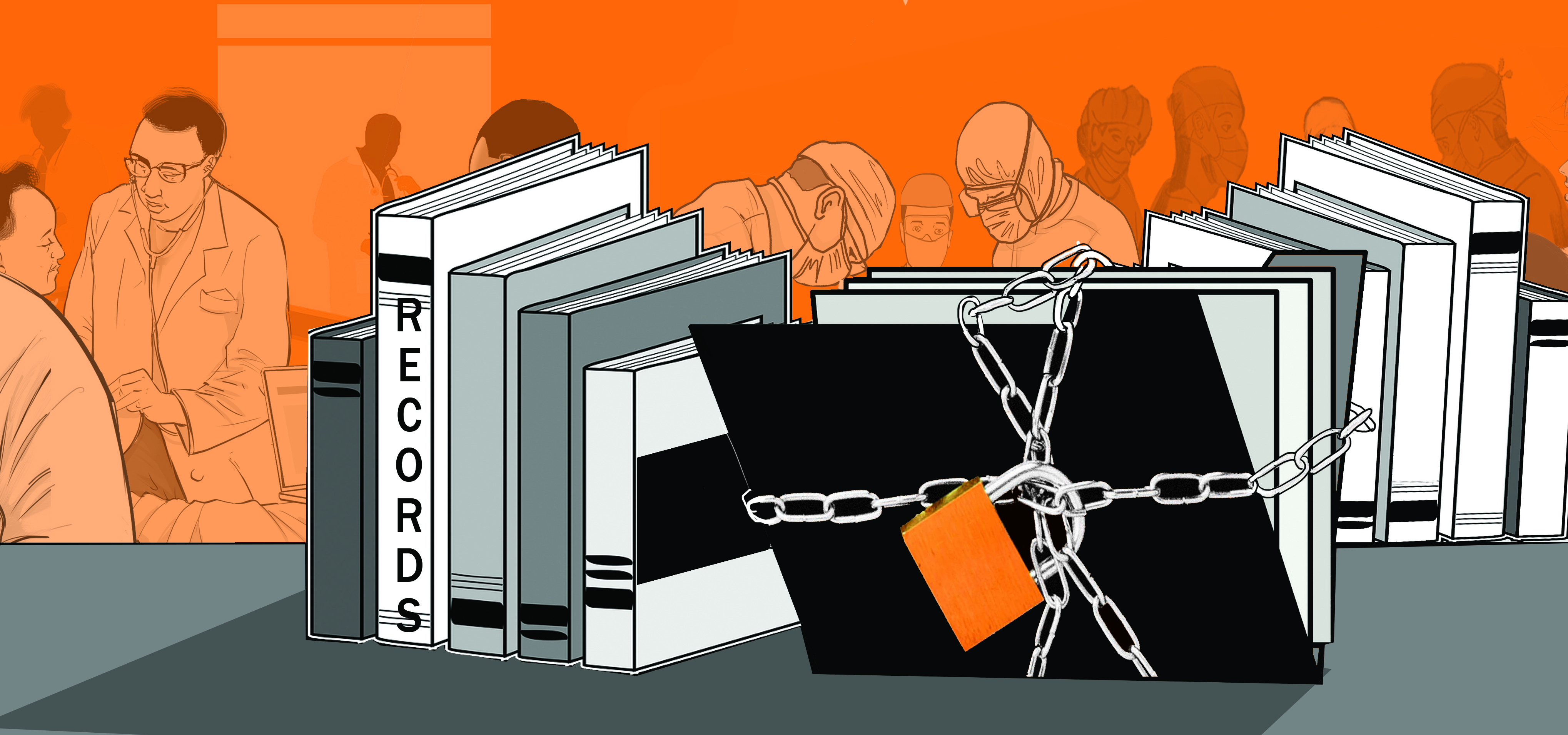

The first reality the public must confront is that hospitals cannot disclose the very information needed to answer the questions being asked. Kenyan law treats medical information as some of the most tightly protected data. The Health Act makes all treatment information confidential. The Data Protection Act classifies health data as sensitive personal data. Professional ethics demand confidentiality even after death.

These are binding rules, not suggestions. A hospital may express condolences. It may affirm that certain circulating claims are inaccurate. It may outline general emergency policies.

But it cannot reveal any information that identifies a patient’s clinical condition, emergency presentation, diagnosis, stabilisation process, treatment decisions, financial discussions or internal records. Even confirming whether a deposit was requested or waived is a disclosure of private medical and financial information.

To the public, this silence feels evasive. To the hospital, it is the only lawful option.

This creates an information asymmetry that social media amplifies. Individuals online can speculate freely. They face no legal duty of accuracy or confidentiality. They are not restricted by regulatory, ethical or professional obligations. Hospitals, bound by law, cannot enter that arena without risking litigation or discipline.

This tension often leads to a misguided conclusion that a hospital’s limited statements are evidence of wrongdoing. Yet the restriction is structural, not strategic.

There is another question the public must ask themselves. If you were the patient, or if it were your spouse, child or parent, would you want your medical details circulated online to satisfy public curiosity? Would you want your lab results, condition, financial constraints or final hours debated on TikTok and WhatsApp?

Most

people would not tolerate that violation. Yet when the patient is someone else,

particularly a public figure, the same people demand complete transparency.

They expect the hospital to break the very confidentiality laws that protect

all of us when our own families are in crisis.

This contradiction is precisely why the law exists. It protects dignity. It prevents health information from becoming public spectacle. It ensures that a person’s final moments are not reduced to social media content.

None of this means hospitals should escape scrutiny. Far from it. There are lawful channels for truth and accountability. The Kenya Medical Practitioners and Dentists Council can investigate. The Office of the Data Protection Commissioner can intervene. Courts and inquests can review complete medical files. These mechanisms exist because they allow full access to records without compromising confidentiality.

Public outrage often demands immediate answers, but medicine cannot operate on the timelines of social media. Transparency must follow due process, not viral tempo.

Until we narrow the gap between what the public expects and what the law allows, tragedies will continue to be followed by confusion, online accusations and institutional silence. The path to clarity is not through forcing hospitals to break the law. It is through strengthening public understanding of confidentiality, supporting formal investigations and grounding our reactions in principle rather than speculation.

Silence from a hospital does not automatically mean guilt. It often means something far simpler. The law is doing exactly what it was designed to do.