Impeachment has always stood at the crossroads of law and politics.

In The Federalist Papers of 1788, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison and John Jay warned that such trials would “seldom fail to agitate the passions,” as they mix questions of misconduct with partisan rivalries.

Kenya’s experience with impeachment, whether of a deputy president, governor or deputy governor, has consistently reflected this delicate balance.

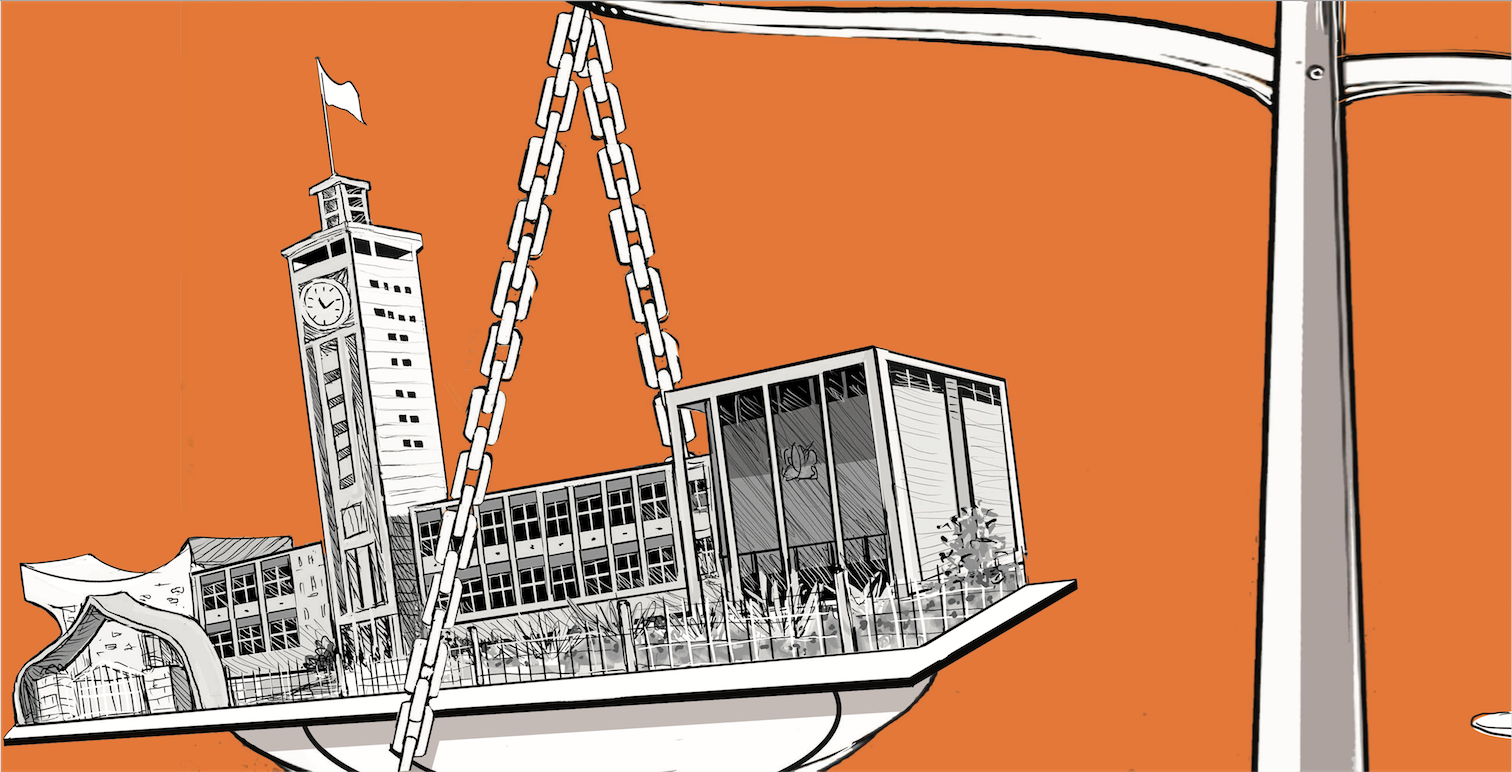

The 2010 constitution sets impeachment as a high bar, intended as a safeguard to remove leaders genuinely guilty of abuse or misconduct. But the history of impeachment since devolution shows the constant tension between that noble intention and raw political convenience.

The dramatic ouster of former Nairobi Governor Mike Sonko in December 2020 proved that impeachment can indeed unseat a leader. But it also exposed the backroom negotiations and political influence that drive such processes.

Since then, 11 governors and three deputy governors have faced impeachment motions. Only three governors, Sonko, Ferdinand Waititu of Kiambu and Kawira Mwangaza of Meru, alongside Kisii Deputy Governor Robert Monda, were successfully removed.

Most survived not because the charges lacked merit, but thanks to party loyalty, lobbying or deep pockets. Some, like Martin Wambora and Mwangi wa Iria, found reprieve in the courts. Others, like Anne Waiguru, leaned on political machinery to stay in office. The repeated attempts against Mwangaza in Meru showed how impeachment can be wielded as a blunt political weapon.

The October 2024 impeachment of Deputy President Rigathi Gachagua marked the most seismic moment yet. With 281 MPs voting in favour and the Senate upholding five charges, he became the first deputy president removed under the 2010 Constitution.

Months later, Nairobi Governor Johnson Sakaja faced a similar scare when 64 out of 85 MCAs backed his removal. But a swift intervention by ODM leader Raila Odinga and President William Ruto killed the motion, fueling speculation of political debts, hidden skeletons or questions of loyalty.

Impeachment matters because it goes to the heart of Kenya’s fragile democracy. At its best, it is a shield against impunity, forcing leaders to answer for misuse of office. At its worst, it is a bargaining chip, exchanged in smoky rooms where survival depends on who owes who.

The credibility of this tool lies not in how often it is used, but in whether it delivers justice fairly, without fear or favour.

Beyond Kenya, global standards insist that accountability must remain central. The UN Convention Against Corruption calls for integrity among public officials. The African Union Convention urges credible systems to curb abuse of power. The Commonwealth Latimer House Principles stress that impeachment should protect constitutionalism, not undermine it.

The danger for Kenya is clear because when misused, impeachment turns governance into a game of survival. Governors spend more time striking deals with MCAs than delivering services. National leaders shield allies or pursue rivals, while citizens are left watching as hospitals decay, schools falter, and roads crumble.

Still, impeachment cannot be dismissed. In cases like Waititu and Sonko, it struck with precision. The fall of Gachagua brought vindication and unease, showing no office is untouchable, yet also how power games shape justice.

The real test now is to rescue impeachment from political drama and restore its dignity. Used with integrity, it protects democracy. Misused, it reduces governance to spectacle.

Program Manager for Inclusion and Political Justice at the Kenya Human Rights Commission