About 50 years ago, a major cause of concern for the two most populous countries in the world – India and China – was how to bring their high population growth rates under control.

In the short term, China’s somewhat drastic one-child-per-family policy proved to be the more effective in reducing the population growth rate. India, with a variety of initiatives, some more brutal than others, also managed to slow down the rate at which its population was rising.

The funny thing here is that a lot of this panic was the result of a very influential book, The Population Bomb by Paul Ehrlich, which predicted global famine and a depletion of natural resources given the trajectory of population growth around the world.

He convinced many influential policymakers that an existential disaster was just around the corner given that the global population was rising in an “unsustainable” manner.

Why do I say this is funny?

Well largely because for many of the richest countries in the world, the problem currently faced by many policymakers is that of populations that are declining rather than increasing. With the possible exception of the US, for much of the West, as well as the rich nations of East Asia, the problem is one of too few children being born.

The widely accepted root cause of this – of why there has yet to be any such 'population bomb' exploding anywhere on earth – is a deceptively simple factor: the increasing ease of access to education for women.

Once women have access, especially to tertiary education, they cannot remain as stay-at-home spouses: they will seek careers just like men do. And in the process will invariably have fewer children, or even no children at all.

And so, for these nations with declining populations, there is a need to adopt strategies to encourage immigration, ideally of skilled workers, but also of non-skilled workers who would happily accept the jobs that the indigenous populations simply do not want to do.

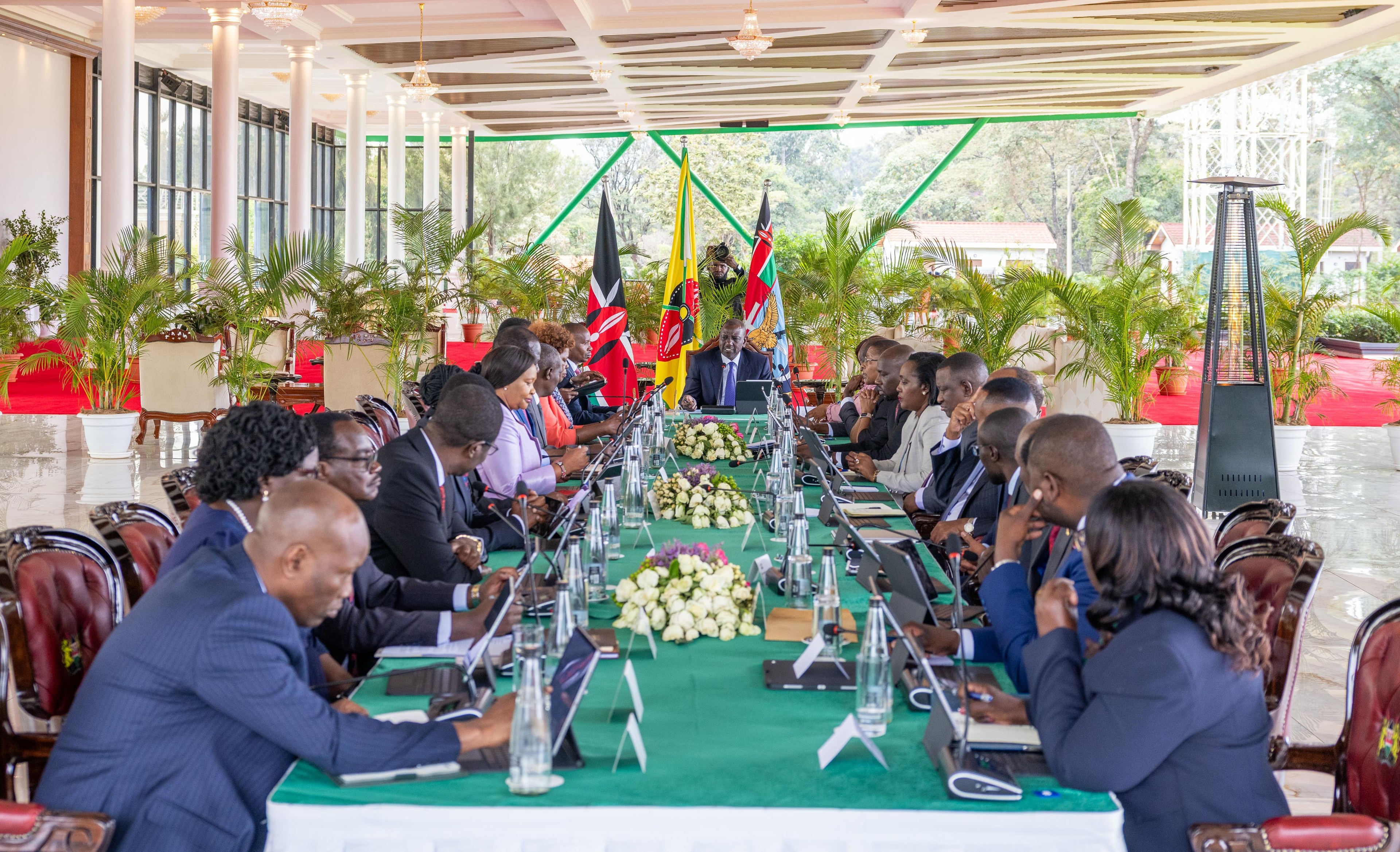

It is against this global trend that President William Ruto’s regular mentions of the jobs he is seeking abroad for young Kenyans must be seen. The demand for guest workers is definitely there.

And given that Africa is one of the places with plenty of young unemployed people willing to do just about any job – skilled or menial – to earn a living, it all points to more and more young Africans seeking employment opportunities overseas.

But there is a problem. Although the US has had its serious challenges with race relations – from its infamous Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882; to 250 years of slavery for African Americans; to innocent Japanese US citizens being held in internment camps during World War II – it is the US that overall has been most welcoming to immigrants.

But in much of Europe, there is a visceral dread of “replacement” – foreigners coming over in such large numbers as to fundamentally distort the culture, traditions and ethnic composition of a country.

So, there are, on the one hand, countries in which there is a definite need for imported labour (ie, more immigration); but in the same countries – and on the other hand – there is fierce resistance to having foreigners come and settle among the local people.

And yet from our Kenyan point of view, this possibility of increasing demands for our young people’s labour in those distant lands is a great economic opportunity.

Not just that the young Kenyan (provided he seeks these opportunities through the right channels) will find a job abroad when he had none at home. But such a young Kenyan will usually send a good part of his earnings back home, to support the family, or to invest.

Now one thing for sure is that economic growth can be very effectively driven by consumption.

And having all this extra money coming into Kenya as “diaspora remittances” is definitely a huge economic boost: the money may come from outside, but it is spent right here, providing incomes for local producers of goods and services.

![[PHOTOS] Ruto present as NIS boss Noordin Haji's son weds](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcdn.radioafrica.digital%2Fimage%2F2025%2F11%2Ff8833a6a-7b6b-4e15-b378-8624f16917f0.jpg&w=3840&q=100)