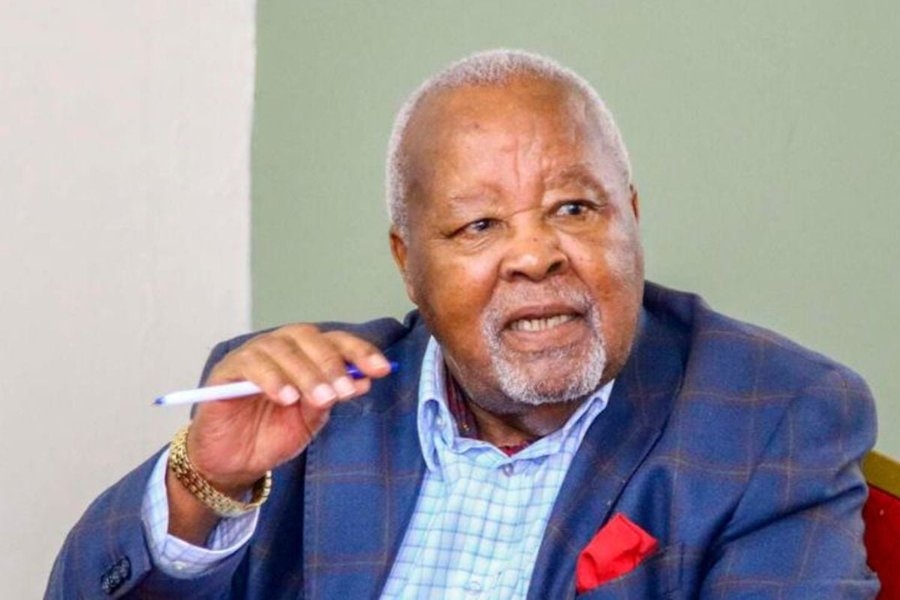

Kenyan, Evans Kibet, surrendered to Ukrainian Forces after

he was allegedly forcefully recruited into fighting for the Russian military.

This followed his visit to the country before he was offered

a job, signed documents and found himself in a military training camp.

Following his surrender, he now remains in Ukraine as a

Prisoner of War among others from different nationalities across the world.

While images of captivity often evoke fear and uncertainty,

a robust framework of international law exists to separate the treatment of

captives from the brutality of the battlefield.

At the heart of this system is the Third Geneva Convention

of 1949, a treaty ratified by 196 countries that serves as the "bill of

rights" for captured soldiers.

But as conflicts evolve from traditional state-versus-state

battles to complex insurgencies involving private contractors and non-state

actors, these decades-old rules are facing new and unprecedented tests.

Not everyone captured on a battlefield is a Prisoner of War

(POW).

The coveted POW status—which grants immunity from

prosecution for lawful acts of war—is reserved for ‘lawful combatants.’

According to Article 4 of the Third Geneva Convention, to

qualify as a POW, a captive must generally belong to the armed forces of a

party to the conflict.

However, militias, volunteer corps, and resistance movements

can also qualify, provided they strictly meet four conditions including being commanded

by a person responsible for their subordinates and have a fixed distinctive

sign recognizable at a distance (like a uniform or armband).

They must also carry arms openly and conduct operations in

accordance with the laws and customs of war.

If a fighter fails these tests—for instance, by hiding

weapons to blend in with civilians—they may be classified as an "unlawful

combatant."

These individuals do not enjoy POW immunity and can be

prosecuted under the detaining nation’s domestic laws for their participation

in hostilities, though they still retain fundamental human rights protections

against torture and summary execution.

Rights of a POW

Once POW status is established, a comprehensive protective

regime kicks in.

The predominant principle is simple: POWs are not criminals.

They are merely soldiers "out of the fight,"

detained solely to prevent them from returning to the battlefield.

Under international law, a POW is required to give only

their surname, first names, rank, date of birth, and army serial number. This

"name, rank, and serial number" rule is absolute.

No physical or mental torture, nor any form of coercion, may

be inflicted to secure military intelligence.

Prisoners who refuse to answer cannot be threatened,

insulted, or exposed to unpleasant treatment.

The detaining power is responsible for the health and upkeep

of POWs. This goes beyond mere survival; it includes food, which must be as

favorable as those provided to the detaining power's own forces in the same

area.

Sick or wounded prisoners must receive the same medical attention

as the detaining army, have full liberty to practice their religion and attend

services and effects and articles of personal use (except weapons) must remain

in their possession.

Contrary to popular belief, POWs can be made to work, but

with strict caveats. Officers cannot be compelled to work, and non-commissioned

officers can only be required to supervise.

For enlisted personnel, labor is authorized but must not be

military in character (e.g., they cannot be forced to manufacture weapons to be

used against their own side).

Remarkably, the Convention even stipulates that POWs should

be paid.

Detaining powers are expected to provide "working

pay" and a monthly advance of pay to allow prisoners to purchase small

comforts like soap or tobacco, ensuring a semblance of dignity and normalcy.

The 1949 Conventions, however, were written for a world of

uniformed armies fighting across clearly defined borders. Today’s conflicts

often look very different, creating legal "gray zones."

Private Military Contractors

The status of employees for companies like the former

Blackwater (now Academi) or the Wagner Group (now Africa Corps) is legally

murky.

Generally, if they are not formally incorporated into the

armed forces, they are considered civilians.

This means they lack the "combatant's privilege"

(the right to kill without being charged with murder) and do not automatically

qualify for POW status if captured, leaving them vulnerable to criminal

prosecution.

Terrorists and Spies

Groups that systematically target civilians or fight without

uniforms often fall outside the POW definition.

However, legal experts stress that no one is in a

"legal black hole."

Even those denied POW status are protected by "Common

Article 3" of the Geneva Conventions, which prohibits murder, mutilation,

torture, and humiliating treatment of anyone in detention.

Enforcing these rights falls largely to the International

Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).

The Geneva Conventions grant the ICRC a unique mandate to

visit POW camps, interview prisoners in private (without guards present), and

facilitate communication with their families through "Red Cross

Messages."

This access serves as the primary check against abuse,

ensuring that the detaining power knows the world is watching.

The final right of a POW is the right to leave.

Article 118 states that "Prisoners of war shall be

released and repatriated without delay after the cessation of active

hostilities."

They cannot be held as bargaining chips or punished for the

mere act of fighting for their country.

![[PHOTOS] Three dead, 15 injured in Mombasa Rd crash](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcdn.radioafrica.digital%2Fimage%2F2025%2F11%2Fa5ff4cf9-c4a2-4fd2-b64c-6cabbbf63010.jpeg&w=3840&q=100)