In 1978 Nasa announced 35 new astronauts for a new era of spaceflight – and six of them were women. Here's how the Space Shuttle programme chipped away at one of Nasa's blind spots.

On 18 June 1983, Space Shuttle Challenger prepared for launch. STS-7 was Nasa's seventh Shuttle mission for the world's first reusable spacecraft. On board, among its crew of five, was Californian physicist Sally Ride. Until then, only two women had ever been into space.

Soviet cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova had made history more than two decades earlier in 1961. Nineteen years later, in 1982, Svetlana Seviskaya became the second woman in space after the Soviets got wind that the US was going to fly its first woman. Although an astronaut Barbie doll appeared in US shops in 1965 – sporting practical boots and a silvery spacesuit – American women had to wait a lot longer for the real thing.

By the 1980s both the world and fashion had changed. The revamped 1985 astronaut Barbie sported glittery silver leggings and had a matching handbag. There were fuchsia-pink puffed sleeves, a short skirt and pink knee-length high-heeled boots.

While heels were definitely not part of Ride's mission accessories, Nasa did provide cosmetics in the form of mascara, eye shadow and lipstick. They were inside a Personal Preference Kit (PPK) for its six new female astronauts: Ride, Judy Resnik, Anna Fisher, Kathryn Sullivan, Shannon Lucid and Rhea Seddon.

Ride, it turned out, did not use the make-up.

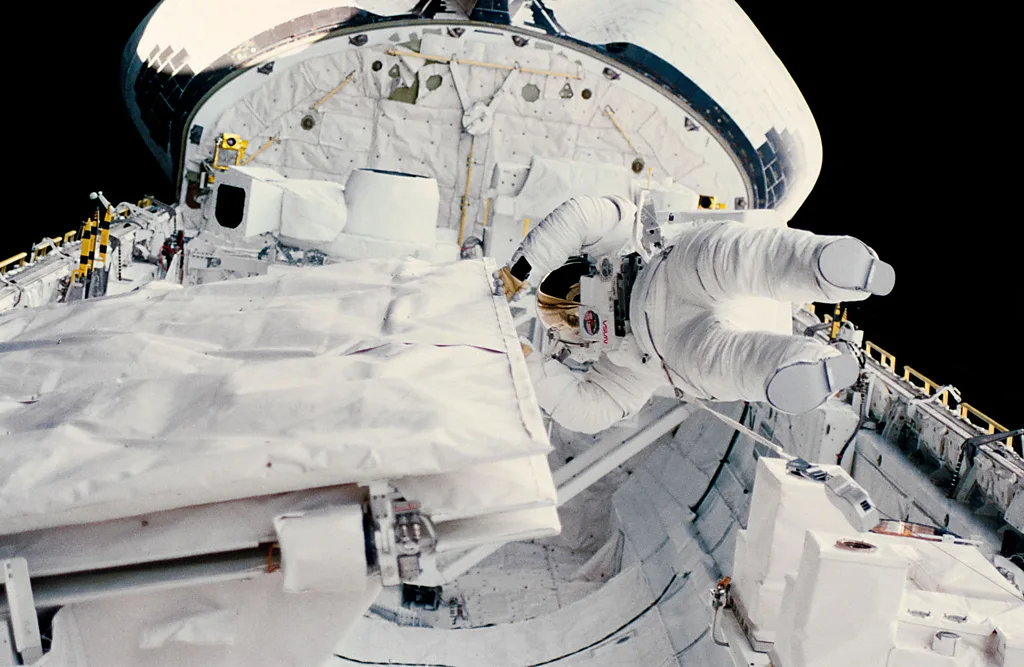

Neither did her astronaut trainee colleague Kathryn Sullivan, a year later, when she became the first American woman to perform a spacewalk.

"Several of us reacted with a mix of bemusement and annoyance at the 'Female PPK' cosmetic kit," says Sullivan, who later played a crucial role repairing the Hubble Space Telescope and is co-author of How to Spacewalk: Step-by-Step with Shuttle Astronauts.

"A whole kit devoted to make-up suggested to me that someone thought we might be less mission-focused than our male counterparts, or we were obliged to live up some journalistic stereotype," says Sullivan.

They put some tampons in the PPK for Sally to look at and she pulled one out and it was like unreeling a string of sausages – Kathryn Sullivan

Not every female astronaut from this intake, however, eschewed the cosmetics. Seddon recalls on her website: "I spoke up for the minority. If there would be pictures taken of me from space, I didn't want to fade into the background so I requested some basic items… It was interesting to me that that I wasn't the sole space traveller whose in-flight pictures showed a bit of lipstick and blush".

Ride never wore make-up but there were other issues with the PPK. "The women had already lobbied to replace the British Sterling deodorant, the men's hair tonic and the Old Spice shaving cream with more female-friendly lotions and potions," says Lynn Sherr, author of Sally Ride: America's First Woman in Space.

But, on some occasions, the sex of those six astronaut trainees was simply forgotten. "Back in 1978, when she was invited to Edwards Air Force Base to see the test landing of Space Shuttle Enterprise," says Sherr, "every visiting astronaut – including the women – received souvenirs of the occasion: gold-plated Shuttle tie clips and cufflinks".

While personal preferences will differ, one aspect of space travel preparation for the new recruits required a basic knowledge of biology.

"The Nasa guys had realised that women might be women and therefore, while they were flying, it might be the time of the month when they got their periods," Sullivan told me in an earlier interview.

"They put some tampons in the PPK for Sally to look at and she pulled one out and it was like unreeling a string of sausages. Tampon, tampon, tampon, tampon, tampon. There were like 100. And they said, is that enough? Sally was hysterical and said, 'No, no'. She thought that was really too much, thank you very much."

As you may have

gathered, Nasa had the engineering know how to get into space but not

necessarily a full understanding of a woman's priorities, or even their

menstrual cycle. "The most obvious and amusing missteps were in crew

equipment – clothing, parachutes, helmets, hygiene needs," says

Sullivan. "I think these were all innocent gaffes, and that the teams

responsible for those did the best they could with what they knew."

While not everything hit the mark for the women, Nasa did get things right too.

Male and female bladders may be essentially the same but, as anyone with young children will attest, the pressure points for urine absorbency in a baby boy's nappy are not the same as those for a girl's.

Nasa had already designed a Maximum Absorbency Garment (MAG) – an adult nappy (or diaper) worn during launch, landing and spacewalks. But until the Shuttle intake every US astronaut had been male. Since the women were also of varying height and build (and on average are shorter and weigh less than men), Nasa made them individual "disposable absorption and collection trunks".

"Nasa had made the commitment to accepting women into the programme," says class of 1978 astronaut Anna Fisher in the radio documentary The Equal Rights Stuff. "Even if you looked in mission control, there were women," Fisher says, "but very few flight controllers, certainly no female flight directors. The first female flight director wasn't until 1984."

Historically there had also been an assumption among US astronauts that only men had 'the right stuff'. Up until the Space Shuttle selection, all but one of Nasa's astronauts were pilots and had a background in the military. Harrison Schmitt was the sole exception. A geologist on Apollo 17, he still completed jet and helicopter flight training at two military bases as a civilian.

It didn't take long to realise that these people brought a lot to the table – Mike Mullane

Suddenly the 'normal' rules of astronaut selection no longer applied. Sure, 15 of the "35 new guys" were pilots, but this time they were outnumbered by 20 mission specialists: scientists, physicians or engineers. Not only that, but six within this new category were women, and not everyone was happy about it.

"I know Mike Mullane was very forthcoming about his feelings in his book Riding Rockets," Fisher says.

When Mullane joined the Shuttle astronaut corps he was a pilot, had attended the all-male West Point US Military Academy and was a Vietnam veteran of 134 combat missions.

"He wondered how these people coming from a scientific background were going to function," says Fisher, "if you found yourself in a life-threatening situation."

Despite being extremely well qualified, these women constantly had to prove themselves

When I met Mullane at his New Mexico home a few years ago, he was as forthright as in his book about his sexism at the time, as well as his perceived shortcomings of the women and other mission specialists.

"You come out of Catholic school, you learn that women only have a couple of functions. The prime role of a women is to be a mother and stay at home wife," says Mullane. "That was what was hammered into to us all those years. So it was very unusual to meet women who were not dental hygienists or secretaries.

"I was suspect and most military were suspect about how these people would adapt to a world so different. For us it was the same world flying high-performance vehicles. It didn't take long to realise that these people brought a lot to the table," said Mullane. "On my first mission I was assigned to a crew that included Resnik, the second woman to fly in space. Loved her."

Mullane admits to a rocky relationship with Ride but was later full of admiration at what she had achieved. "Sally showed she really did have the right stuff."

During the six women's training, their inclusion was often met with incredulity or ridicule.

"One reporter pointed out that men had done all the piloting and spacewalks and science in Mercury, Gemini and Apollo, and surely could do so on the Shuttle," says Sullivan. "So weren't we unnecessary or just along to watch the men?"

This attitude extended far beyond news programmes. "Johnny Carson joked on The Tonight Show," says Sherr, "that the Shuttle would be delayed so that Sally could find a purse to match her shoes."

Sherr, a former Shuttle commentator, was at the pre-flight press conference for STS-7 when a Time Magazine reporter asked Ride about her response to a glitch or problem during training: "Do you weep?"

Despite being extremely well qualified, these women constantly had to prove themselves. Ultimately, they succeeded with each mission. Lucid, for instance, flew five times, performed invaluable research and held the world record for the most time in space by a woman from 1996 to 2007.

But the important thing was to be selected in the first place and actress Nichelle Nichols played a key role in realising the most diverse class of US astronauts Nasa had ever assembled.

Nichols was best known as the original Lieutenant Uhura in the 1966-69 Star Trek TV series, and the only black actor who regularly appeared in the original show.

Nichols' position on the bridge of the USS Enterprise had a powerful

impact on Americans. So Nasa enlisted her for recruitment videos to

encourage women and people of colour to apply. She also gave school

talks and later made the 1979 National Air and Space Museum promotional

film What's in it for me?

Three African Americans and one Asian American were among the 35 trainees and, before her death in the Challenger accident, Resnik (the first American Jewish woman in space) often spoke about how Nichols encouraged her to become an astronaut. Years later Mae Jemison – Nasa's first black woman in space in 1992 – also cited Nichols as an inspiration.

Nasa today is a completely different organisation. Engineering mission specialist Loral O'Hara joined the crew of the International Space Station (ISS) in and joined Kurdish-American Jasmin Moghbeli, who has an equally impressive engineering background as well as being a test pilot with over 150 combat missions under her belt – a reminder that the 'the right stuff' is no longer the preserve of white males.

"Sally Ride's position was it took Nasa 20 years to get there but, once they made the decision to include women and minorities, they were all in," says Sherr.

"I think Sally saw Nasa as the equal opportunity employer it had finally become."

You can hear more about Nasa's efforts to widen the pool of Space Shuttle crew in this episode of the BBC radio series 13 Minutes Presents: The Space Shuttle on BBC Sounds.

![[PHOTOS] China holds massive parade to mark 80th anniversary of WWII](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcdn.radioafrica.digital%2Fimage%2F2025%2F09%2Fbd5dfa7a-3a06-486e-b6b0-6b032c0ffc73.jpg&w=3840&q=100)