Nyeri youth click living from street photography

University graduate Wanjohi makes at least Sh700 daily on weekdays

Policy move empowered them and paved the way for a popular culture

In Summary

Audio By Vocalize

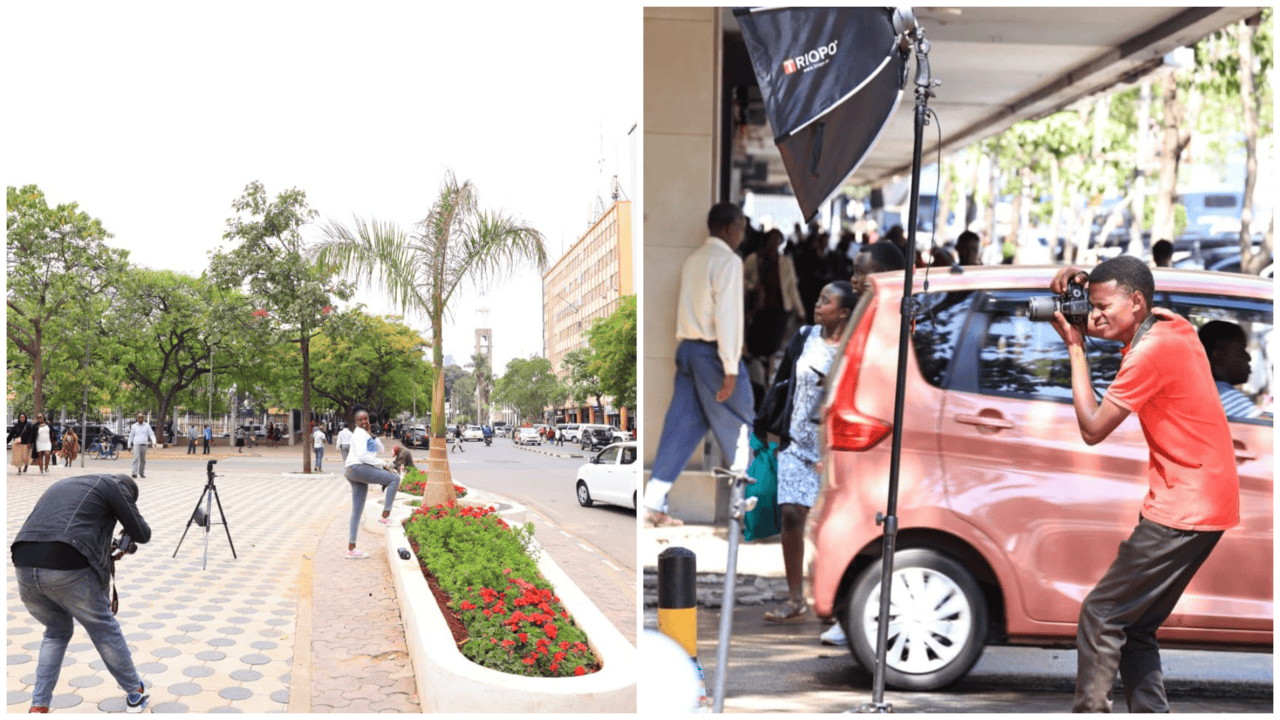

Street photographers Alex Etyang(R) and Simon Waweru (L) at work in Nairobi CBD.

Street photographers Alex Etyang(R) and Simon Waweru (L) at work in Nairobi CBD.

On a typical weekday, Nairobi CBD hums with relentless motion, matatus hooting, traders calling out to customers and hurried footsteps echoing through the streets.

Space is scarce, time even scarcer.

But come Saturday or Sunday, the tempo softens. The same streets that choke with weekday rush transform into open studios, places where Nairobi’s youth turn creativity into cash.

Walk through Kenyatta Avenue, Moi Avenue or River Road on a weekend, and you’ll see them everywhere — young men and women armed with cameras, tripods and smartphones.

They approach passers-by politely, asking, “Can I take your picture?” For a small fee, they capture portraits, fashion shots or short clips meant for TikTok and Instagram reels.

What looks like a casual pastime is, for many, a full-time job, a way to survive in a city where opportunities are few but dreams are many. And it has all been made possible by a single policy that opened the streets to creativity.

Only a few years ago, photography in Nairobi’s city centre was a privilege reserved for those who could pay.

Street photographers were required to obtain costly permits from City Hall, with fees starting at Sh5,000.

Those who could not afford them often faced harassment, extortion or arrest by city askaris.

For a generation of young people struggling to find work, the policy was more than a bureaucratic burden; it was a wall blocking their ambitions.

“Back then, you needed a permit for every session,” recalls Simon Waweru, a 24-year-old photographer from Pipeline Estate.

“If you didn’t have one, askaris would stop you, take your camera, or ask for a bribe. Many of us simply gave up.”

Waweru’s story is familiar to hundreds of youth who once dreamed of making a living through photography or videography.

Without access to studios or permits, many talents went unnoticed and unfulfilled.

TURNING POINT

In 2022, shortly after taking office, Nairobi Governor Johnson Sakaja scrapped all photography and videography permit fees in the city.

“Photography is an art that speaks without words,” Sakaja said at the time.

“Around the world, people make a living and build brands through it. We want our youth to prosper, to do what they love while earning a decent living. That’s why we removed the photography permits.”

The announcement was more than a statement; it was an invitation. One that opened the streets to thousands of creators who had been waiting for their chance.

Today, the same streets that once felt off-limits have become Nairobi’s biggest open-air studio.

Alex Etyang, a street photographer who charges Sh100 per photo, says the policy completely changed his life.

“I’m a graduate and walked for months without finding a job. When Governor Sakaja allowed free street photography, I found my breakthrough. I now make a living doing what I love — taking photos and meeting people,” he says.

“Before Sakaja’s move, we had to get permits and often faced harassment from county askaris. We are grateful because we can now work freely and earn from our creativity.”

For Waweru, photography has gone from passion to profession.

“I love photography, it’s something I’ve always wanted to do,” he says, crouched on the pavement near Kenyatta Avenue as he adjusts his camera.

“Buying a camera is one thing, but setting up a studio is costly. Before I gave up, I realised our streets are our studios. We shoot for free and make a living. Street photography pays my bills.”

On a good weekend, Waweru earns between Sh2,000 and Sh4,000, depending on the crowd and location.

Most of his clients are young Nairobi residents looking for stylish portraits, or couples taking weekend photos.

“Sometimes people just want one good photo for their WhatsApp or TikTok profile,” he says with a grin.

“That’s all I need to survive the week.”

FROM HUSTLE TO HOPE

A few blocks away, Isaac Masai from Kasarani carries a Nikon camera that he bought second-hand from a friend.

He once worked as a casual labourer at construction sites but now spends his weekends taking portraits on Kimathi Street.

“Getting a job in this city is not easy,” he says.

“But with street photography, you just convince someone to take a photo, and you earn. You don’t need capital, just a camera. This opportunity has changed many lives.”

Masai and his friends have even created a small WhatsApp group where they share editing tips, client referrals and photography tricks.

“When one of us gets a big gig, maybe a wedding or birthday shoot, we call the rest to help. We all grow together,” he says.

Not all who benefited from Sakaja’s policy are photographers. Some are videographers and digital content creators who now use the CBD as their creative playground.

TikTokers film dance challenges on Moi Avenue, YouTubers record street interviews near the Kenya Archives, others shoot short skits, fashion reels or cinematic videos featuring Nairobi’s skyline.

Brian Eddy, a college student, says this freedom has helped him finance his education.

“I don’t get full financial support for my studies,” he says.

“But with a camera and no permits required, I can make money to pay my school fees. If it weren’t for Sakaja’s directive, I don’t know how far I’d have come.”

Eddy earns about Sh3,000 per weekend, enough to cover transport and basic needs.

“I’m not just surviving,” he adds, “I’m learning, connecting and growing.”

RESILIENCE AND REINVENTION

For David Safari from Mukuru Kayaba slum, photography is more than an income; it’s empowerment.

“It’s not easy to make it from the slums, but free photography has been a dream come true,” he says.

“I make a living out of this and have mentored other young photographers, who now earn from it.”

Safari started with a borrowed camera in 2023.

Today, he runs small weekend workshops in South B, where he trains other youth on basic photography and editing.

“I’ve seen kids who had no hope now earning something every weekend. It’s not charity, it’s opportunity,” he says.

City Hall’s directive has done more than boost individual incomes; it has redefined Nairobi’s creative economy.

Public spaces, once viewed as congested or chaotic, now double as creative zones.

Every weekend, locations like the Nairobi Railway Station, Kenyatta Avenue, and Tom Mboya Street buzz with youthful energy, cameras clicking, lights flashing and laughter echoing.

The CBD has become a vibrant showcase of Nairobi’s artistic pulse.

Content creation, once seen as a niche hobby, is now a livelihood.

The Kenya Film Commission reports a rise in locally produced short films, social media reels, and digital campaigns, much of which originates from these open street spaces.

To complement this wave of creativity, the Nairobi County Mobility and Public Works Department has been upgrading city infrastructure, re-carpeting roads, paving walkways and installing new streetlights.

Public Works chief officer Machel Waikenda says the improvements are part of a broader plan to make the city safer and more attractive.

“We are reclaiming damaged public spaces under the Nairobi Lazima iWork campaign,” he says.

“Better pavements, lighting and drainage mean a cleaner, more beautiful city, one that supports innovation, tourism and creativity.”

These improvements have given street photographers better backdrops and lighting conditions, something many say has elevated the quality of their work.

CHANGING PERCEPTIONS

For ordinary Nairobians, the rise of street photographers has brought unexpected benefits.

“Before, you had to go all the way to a studio, queue for a photo, then wait for it,” says Caroline, a city resident.

“Now, you get it instantly on your phone, and the quality is superb.”

Her friend Nicholas Karuma adds:

“To me, I see hope in our youths. Where would these young people be without this opportunity? The fact that they can now take photos without being harassed shows how much we’ve evolved.”

Indeed, what was once seen as loitering is now viewed as creativity.

Street corners that once echoed with the sound of matatus now hum with conversation, collaboration and inspiration.

In cities like New York, street photography is an accepted and celebrated part of urban life.

Anyone can take photos in public spaces without a permit, as long as they don’t obstruct or invade privacy.

The result is a thriving culture that fuels tourism, art and global storytelling.

Nairobi’s policy shift brings it closer to such creative cities, places where art meets accessibility.

In contrast, countries like Saudi Arabia, the UAE and France maintain tight restrictions, requiring permits or written consent before photographing individuals or public spaces.

By opening its streets to creators, Nairobi has not only embraced freedom of expression but also positioned itself as an emerging African hub for digital creativity.

As dusk settles over the CBD, the golden light glints off building windows while dozens of young photographers chase the perfect shot.

Their laughter blends with the rhythm of the city, determined, hopeful, unstoppable.

What was once an expensive dream is now a way of life. Cameras have replaced despair, creativity has replaced idleness.

For a generation of Nairobi youth, the lens is more than a tool, it’s a passport to dignity, independence and purpose.

And as they capture the faces of strangers, cityscapes and fleeting smiles, they are, in truth, capturing something greater: the story of a city that finally chose to believe in its own young people.

University graduate Wanjohi makes at least Sh700 daily on weekdays