From the Kenya

Revenue Authority’s AI-powered systems boosting daily collections from Sh60

million to Sh1 billion, to the Hustler Fund’s algorithm-driven financial

inclusion for underserved communities, the potential is undeniable.

Yet this rapid

adoption comes with pressing questions about ethics, accessibility and

long-term societal impact that Kenya must address to ensure its digital future

benefits all citizens equally.

The government’s

push for AI integration under the Kenya National Digital Master Plan (2022–32)

has already transformed service delivery, expanding digital offerings from 350

to more than 22,000.

Deputy Chief of

Staff Eliud Owalo envisions a future where physical government offices become

obsolete as digital platforms streamline everything from business registration

to healthcare access.

This digital leap

forward mirrors successes in financial technology, where AI-driven credit

scoring through the Hustler Fund has empowered women-led enterprises and small

businesses previously excluded from formal banking systems.

The fund’s

mobile-based approach demonstrates how targeted AI applications can bridge

Kenya’s persistent economic divides when implemented thoughtfully.

Rongo University vice

chancellor Prof Samuel Gudu says higher education institutions must set ethical

standards for AI use.

“Universities must

lead in setting ethical standards for AI use. Education should not just prepare

students for digital careers but also equip them to navigate AI-driven ethical

dilemmas,” he said.

His stance aligns

with global discourse on responsible AI. A 2022 Unesco report highlighted the

need for ethical frameworks in AI education, warning that unchecked AI adoption

could reinforce biases, infringe on privacy and undermine human

decision-making.

Rongo University has integrated AI ethics into its curriculum, ensuring students develop both technical skills and critical awareness.

PROMISE AND PERIL

One of Kenya’s

most tangible AI success stories is in revenue collection, as noted earlier. AI-powered

systems that detect tax evasion and seal financial leakages have significantly increased

collection.

“The sources of

revenue remain the same, the people in government remain the same, but we’ve

leveraged technology to enhance efficiency,” Owalo said.

This efficiency

has strengthened Kenya’s fiscal independence, reducing reliance on external

debt.

Beyond finance, AI

has revolutionised service delivery. Under the Kenya National Digital Master

Plan (2022-32), government services have expanded from 350 to more than 22,000

digital offerings.

Owalo predicts

that soon, “physical visits to government offices will be unnecessary as

digital platforms streamline services”.

Education presents

both AI’s promise and peril. Universities like Rongo have taken proactive steps

by integrating AI ethics into their curricula, preparing students for a

workforce where human judgment must complement machine intelligence.

Dr Maren Akong, a

lecturer and Writers Club patron, calls for moderation. “AI should enhance

creativity, not replace it.”

This concern comes

as studies indicate that 40 per cent of Kenyan university students now use

tools like ChatGPT for assignments, raising valid concerns about academic

integrity and the erosion of critical thinking skills.

University

students remain deeply divided about AI’s role in academia and creative fields,

reflecting broader global debates about technology’s impact on learning and

originality.

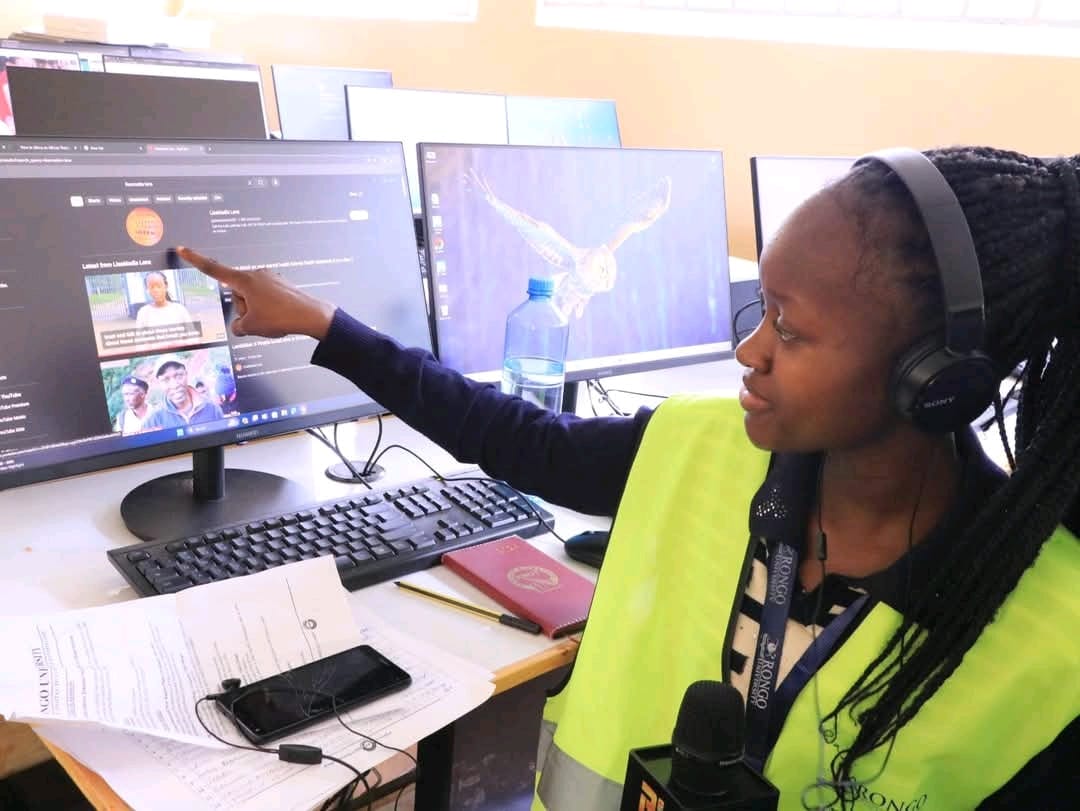

Lisa Ajiambo, a

fourth-year communications student and digital content creator, utilises AI

tools for video editing and audience analytics but says one should not get

carried away.

“There’s a

dangerous tipping point where convenience can erode authentic creativity,” she

says. Her concerns echo findings from a 2023 African Academic AI Network study,

showing 62 per cent of creative arts students struggle to maintain originality

when using generative AI.

The anxiety about

AI’s cognitive impact extends beyond creative disciplines. Francis Oluoch, a

second-year education major at Maseno University, worries about its

implications to his future career.

“When my classmates use AI to generate lesson plans or solve math problems, they are skipping the mental gymnastics that make us better teachers,” he says.

MODERN LEARNING

Some students are

more optimistic, championing AI as an essential tool for modern learning.

Purity Anyango, a first-year media studies student at Rongo University, is in

this school of thought.

“AI doesn’t

diminish our creativity, it gives us more time to focus on big ideas by

handling technical tasks like colour correction or audio balancing,” she says.

Her experience

reflects broader trends identified in Unesco’s 2023 Global Education Monitoring

Report.

The report

highlighted how AI-assisted editing tools can increase media students’ output

quality by 40 per cent when used as supplements rather than replacements for

human judgment.

As noted, students’

perspectives range from cautious skepticism to enthusiastic adoption.

This mirrors the

broader societal negotiation occurring as AI transforms workplaces.

The students’

insights suggest that educational institutions must strike a delicate balance.

They should equip

students with cutting-edge AI skills, while preserving the human elements of

creativity, critical thinking and ethical judgment that remain invaluable in

the digital age.

As these youths prepare

to enter the workforce, their ability to navigate this balance may determine

not just individual success but also the nation’s capacity to harness AI as a

tool for inclusive development.

The employment

landscape is similarly in flux. While global reports predict AI could displace

85 million jobs worldwide by 2025, Kenya’s unique ‘hustler economy’ may prove

more resilient.

Startups like

Ushauri AI, which provides Swahili-language agricultural advice through

chatbots, demonstrate how homegrown solutions can create new opportunities

rather than simply replace traditional jobs.

The government’s establishment of 180 digital hubs in TVET institutions has already generated 182,000 digital jobs, suggesting Kenya might follow Owalo’s vision where citizens “create jobs rather than wait to be employed”.

ETHICAL DILEMMA

Beneath these

successes lurk significant ethical challenges that could undermine Kenya’s AI

progress if unaddressed.

Algorithmic bias

in financial and government systems risks perpetuating existing inequalities,

particularly against Kenya’s large informal sector workers who lack digital

footprints.

Privacy concerns

loom large as citizens unknowingly surrender personal data to opaque AI

systems, while the rapid spread of AI-generated misinformation threatens to

destabilise elections and public health initiatives. These problems already

emerged during the Covid-19 pandemic. The urban-rural digital divide

exacerbates these issues, with only 42 per cent of rural Kenyans having Internet

access compared to 78 per cent in cities, creating a nation of AI haves and

have-nots in education, healthcare and economic opportunity.

Infrastructure

limitations compound these challenges. Frequent power outages disrupt digital

operations nationwide, while the high cost of AI hardware puts advanced tools

out of reach for most individuals and institutions.

Rural schools lack

the connectivity to implement AI-enhanced learning. Clinics cannot access

diagnostic tools that could save lives. Farmers miss out on predictive

analytics that could transform harvests.

These gaps

threaten to create a permanent technological underclass unless addressed

through targeted interventions.

While AI has

demonstrated remarkable potential to boost revenue collection, expand financial

inclusion and improve service delivery, its unchecked adoption risks

exacerbating existing inequalities. The urban-rural digital divide, algorithmic

biases and ethical concerns in education demand immediate attention to ensure

AI benefits all Kenyans equally.

Three critical

actions must guide Kenya’s AI future: First, policymakers must implement robust

governance frameworks that mandate transparency in public sector AI systems and

protect citizen data rights.

Second,

educational institutions need to dramatically expand digital literacy programmes

that teach both AI applications and their ethical implications.

Third, targeted

investments in rural digital infrastructure, including renewable energy-powered

hubs, are essential to prevent a new technological underclass from forming.

The private sector

and civil society have equally vital roles to play. Tech innovators must

develop localised solutions like Ushauri AI’s Swahili chatbot that address

Kenya’s unique challenges.

Meanwhile, media

and watchdog groups should monitor AI implementations to hold institutions

accountable for biased or exclusionary practices.

Kenya’s choice is

clear: either proactively shape an AI future that serves all citizens, or risk

having that future dictated by unchecked technological forces.

Decisive action should

be taken today through smart regulation, inclusive education and equitable

infrastructure. By doing so, Kenya can become a model for responsible AI

adoption in Africa.

The algorithms of tomorrow are being written today. Let’s ensure they encode Kenya’s values of equity and innovation for all.