Kenya is a leader in environmental matters. We are the global home of the United Nations Environment Programme.The country is also the preferred regional headquarters for many conservation organisations.

Nairobi, our capital, is said to be the only city on earth with a national park. The Masai Mara is famous for its spectacular wildebeest migration. Our landscape is breathtaking. A ride through the Rift Valley is breathtaking.

The Rift Valley lakes host millions of congregating birds. Our hills, plateaus, savannahs and mountains, including the snow-capped Mount Kenya, are exceptional. This diversity of habitats also means a variety of glamorous wildlife, beautiful birds and many creatures.

Most of these species are today found inside places called protected areas. They include national parks, game reserves and forest reserves. Many of these places are now designated as Key Biodiversity Areas (KBA) based on a global standard that uses globally threatened species to identify biodiversity hotspots.

Since they are home to unique species on the verge of extinction, these sites bear global significance, and Kenya is under obligation to ensure that their special wildlife is protected.

Unfortunately, these places are currently under intense human pressure. Tourists are supposed to stay in cities. Of late, there has been a growing trend by the private sector to accommodate them inside protected areas. A few tourist facilities in these areas may be worth considering. However, many hotels are scrambling to establish a presence in protected areas.

In a recent pronouncement, the government banned the issuance of development permits in key wildlife conservation areas in Kajiado, Machakos, Narok, Laikipia, Taita-Taveta and Baringo. This is a commendable move geared towards addressing the unprecedented decline of Kenya's wildlife.

It is an acknowledgement of the urgency to protect some of the country’s vital ecosystems, their biodiversity and humans: a step in the right direction. However, much more is needed. For the ban to achieve meaningful outcomes, the 'net' has to be cast far and wide to cover all KBAs in Kenya.

Protected areas in Kenya were established in the colonial era. As such, their creation was not informed by any science on species distribution. Many of these areas were chosen because they were good hunting or photography sites for colonialists, contained good timber or simply because no one wanted to live there.

Today, using science on species, we have KBAs. These include places outside the protected areas network, like Yala Swamp, Kinangop highland grasslands, Sabaki River Mouth, Dakatcha Woodland and the Kaya forests at the Coast, among many others.

The government seems to have ignored unprotected KBAs, leaving their fate hanging. Yala Swamp is one such wildlife site that is undergoing rampant destruction. The wetland, spread across Siaya and Busia counties in western Kenya, hosts unique biodiversity, including endangered birds, fish and mammals. The swamp is a biodiversity hotspot of global significance.

Beyond its biodiversity value, Yala Swamp provides invaluable ecological services to the region and beyond. The wetland forms a natural buffer against floods, filters and stores freshwater and helps regulate the hydrological cycle. It also serves as a critical carbon sink, helping mitigate climate change by absorbing and storing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Moreover, Yala Swamp provides livelihoods to thousands of local communities. The wetland supplies fish, water for irrigation and domestic use, medicinal plants, pasture for livestock, fertile soils for farming and papyrus for weaving, thatching and other uses.

The need to conserve this wetland cannot be overemphasised. Its protection is critical to biodiversity, the continuity of ecosystem services and local community livelihoods provision.

In 2021, the National Land Commission allocated 6,763.74 ha of Yala Swamp to Lake Agro Ltd despite sustained objections from communities and other stakeholders. The controversial allocation violates the rights of local communities, compromises the ecological services provided by the wetland, threatens its biodiversity and disregards intergenerational equity.

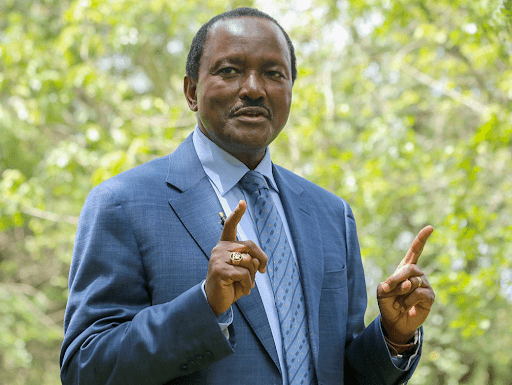

Executive director, Nature Kenya, East Africa Natural History Society