The Supreme Court did not rely solely on its findings about the 11,883 polling stations to overturn the August 8, 2017 presidential election.

The court said there were several missteps the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission made, which led the court to annul the presidential election.

In its 4-2 judgment of September 20, 2017, the Supreme Court emphasized that the IEBC should not focus on the result of a presidential election alone. It said it also mattered how IEBC came to that result for an election to be considered credible.

The judges said lawyers for the IEBC and the commission’s chairperson as well as other advocates argued that what was paramount in an election petition was whether the will of the majority of people prevailed. They said the lawyers argued flaws in the transmission of results should not be a reason to set aside an election. The Supreme Court said these arguments ignored two important factors.

“One, that elections are not only about numbers as many, surprisingly even prominent lawyers, would like the country to believe. Even in numbers, we used to be told in school that to arrive at a mathematical solution, there is always a computational path one has to take, as proof that the process indeed gives rise to the stated solution. Elections are not events but processes,” the judgment read.

There are many issues the judgment analysed when it came to the processes leading to declaring the result of the presidential election of 2017. These included the transmission of results from 11,883 polling stations, which was detailed in Part 1 of this article.

For IEBC to deliver a credible presidential election, it would do well to re-read the judgment. Highlighted below are two other issues that occupied the judges’ minds.

(a) Discrepancies in the result forms received at the National Tallying Centre; and (b) Whether IEBC’s servers were hacked.

DISCREPANCIES IN RESULT FORMS

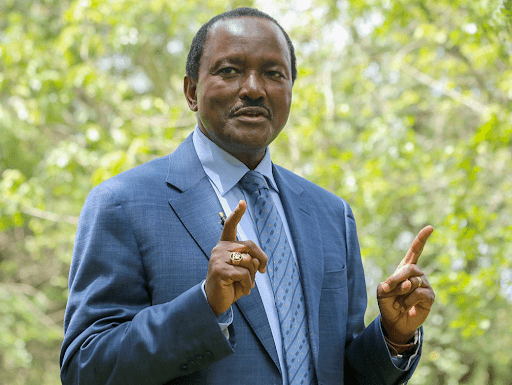

In the petition, Raila Odinga and Kalonzo Musyoka — the presidential candidate and running mate respectively — asked the Supreme Court to order a scrutiny of three categories of results forms.

They asked the court to order the IEBC to provide the originals and copies of Form 34C, Form 34B and Form 34A.

Form 34C is where the electoral commission recorded the national tally of the presidential election. This tally was taken from the presidential election results announced at the constituency level. These results were recorded in Form 34B. The constituency level presidential election results were a tally of those results declared at all the polling stations in a constituency. These were recorded in Form 34A.

The IEBC submitted one Form 34C; 291 Forms 34B; and 40,883 Forms 34A. The court also ordered the Registrar of the Supreme Court to oversee the partial scrutiny of a random sampling of Forms 34A because it would have been difficult to go through all Forms 34A within the tight deadlines the court was working with. Under the Constitution, the Supreme Court has 14 days within which to hear and determine a presidential election petition. The countdown of the 14 days starts when IEBC declares the winner.

The judges said the scrutiny it ordered and conducted “brought to the fore, momentous disclosures.”

“What is this Court, for example, to make of the fact that of the 290 Forms 34B that were used to declare the final results, 56 of them had no security features? Where had the security features, touted by the 1st respondent (the IEBC), disappeared to?

“Could these critical documents be still considered genuine? If not, then could they have been forgeries introduced into the vote tabulation process? If so, with what impact to the “numbers”? If they were forgeries, who introduced them into the system? If they were genuine, why were they different from the others?

“We were disturbed by the fact that after an investment of taxpayers’ money running into billions of shillings for the printing of election materials, the Court would be left to ask itself basic fundamental questions regarding the security of voter tabulation forms,” the judgment said.

The Star asked IEBC to comment on what it was doing to avoid a repeat of the irregularities identified by the court. Despite repeated reminders for comment, the commission had not responded by the time this story was published.

IEBC’s post-election evaluation report did not address or make recommendations to avoid any of the irregularities the court identified in the different categories of results forms.

George Kegoro, executive director of the Open Society Initiative for Eastern Africa, told The Star the forms the IEBC uses are already highly securitised, as a way of preventing fraud.

“Additional securitisation cannot, therefore, be the answer. The answer has to be addressing the human misconduct that enables the abuse that was noted,” Kegoro said, adding that this is not just an IEBC problem.

“The bedrock of Kenya’s electoral politics is intense competition where any shortcut is permitted and where there are high levels of impunity against misconduct that supports winning elections at any cost. The IEBC alone cannot change that culture, and no law can change the culture without a society-wide commitment to do things differently,” Kegoro said.

WERE IEBC’S SERVERS HACKED?

The allegation Raila and Kalonzo made was that throughout the time the IEBC streamed the declared results, the percentages for Kenyatta and Odinga remained consistent. The allegation was that Kenyatta got 54 per cent of the vote while Raila got 44 per cent from the time the first votes were announced to when the final tally was announced.

This consistent pattern could have only happened if the IEBC’s system was hacked, they claimed. They asked the court to order a scrutiny of the commission’s system. The court partially granted the application and also ordered two court-appointed IT experts participate in the scrutiny.

The commission complied with part of the order. It, however, failed to comply with the substantive part of the order, according to the court-appointed IT experts. Some of the orders it failed to follow included not giving information on the configuration of its servers’ internal firewall. It argued doing so would comprise their system.

“The court-appointed ICT experts disagreed with that contention and said it was difficult to ascertain whether or not there were hacking activities,” the judgment said.

Another order that was not complied with was to provide the specific GPRS location of each Kiems kit used during the presidential election between August 5, 2017 and August 11, 2017. Instead, the IEBC provided the court with the GPS coordinates of polling stations.

It also failed to provide the court with the log in trail of users and equipment into two parts of the IEBC system: The commission’s servers and the Kiems database management system. The commission also failed to provide the administrative access log into its public portal between August 5, 2017 and August 28, 2017 (the day the scrutiny order was issued). For all its orders, the Supreme Court granted read-only access to assuage IEBC’s security concerns.

The court said IEBC’s failure to comply left it with no option but to “accept the petitioners’ claims that either the commissions IT system was infiltrated and compromised and the data therein interfered with, or its officials interfered with the data or simply refused to accept it had bungled the whole transmission system and were unable to verify data.”

In its post-election evaluation report, the IEBC denies its system was hacked. It then lists the part of the order it complied with but does not address the issues the court-appointed ICT experts raised.

For the IEBC, this issue goes further than whether it obeyed the Supreme Court’s orders. It was not just in August 2017 that a set voting pattern could be seen on the livestream of the transmission of results.

A similar pattern was also visible in the March 2013 election but the petition did not address similar hacking allegations because it ruled the application and related material submitted to it were time-barred.

In 2013, the IEBC had different commissioners and a different CEO in 2012 from the ones in office in 2017. The issue of the consistent voting pattern seems to transcend personnel. The IEBC will have to address this issue to avoid future hacking claims.

Kegoro told The Star the killing of IEBC’s IT manager Chris Msando in the lead up to the 2017 election left the commission without someone communicating to the public its work, particularly the technology part.

Msando disappeared over the weekend of July 29-30, 2017 and his body found at Nairobi’s City Mortuary on July 31, 2017. His killing remains unresolved.

“Engaging the public as an IT person (at IEBC) is now a risky game, and amounts to drawing attention to oneself which can lead to politically-motivated personal insecurity,” Kegoro said.

Tom Maliti is a journalist who covered the presidential election petitions of 2013 and 2017