Expulsion from a foreign country is a sudden and brutal severing of a life

built on hope and sacrifice.

For thousands of Kenyans living and working abroad, the knock on the door,

the abrupt detention, and the forced repatriation are nightmares that shatter

not just individual lives but entire families and economic ecosystems back

home.

While global headlines often focus on the

geopolitical aspects of migration, the reality for a deported Kenyan is a

descent into a complex web of social stigma, economic paralysis, and emotional

trauma.

This feature examines the harsh journey of a Kenyan citizen stripped of

their diaspora life and thrust back into a home country that often feels

profoundly foreign.

The latest example comes from the United

States, where President Donald Trump’s administration is deporting 15 Kenyan

nationals labelled by his government as the “worst of the worst.”

The individuals were arrested by the U.S. Immigration and Customs

Enforcement (ICE), a federal agency under the Department of Homeland Security

(DHS).

According to DHS, the Kenyans—now branded as “criminal aliens”—have been

convicted of a variety of offences ranging from drink-driving to kidnapping.

“Under Secretary (Kristi) Noem's leadership,

the hardworking men and women of DHS and ICE are fulfilling President Trump’s

promise and carrying out mass deportations — starting with the worst of the

worst — including the illegal aliens you see here,” the department said in a

statement.

The list, released on December 10, shows

arrests conducted across several U.S. states. The Kenyans in detention were

picked up in coordinated raids in Colorado, Texas, California, Arizona,

Tennessee, Utah, Massachusetts, Washington, Georgia, Pennsylvania, and Minnesota.

Their alleged crimes include violent offences, domestic violence, fraud,

drug-related activity, aggravated assault, weapons charges, racketeering,

kidnapping, and other serious criminal conduct.

Deportation, a punitive and administrative act

by a host government, rarely follows a gentle timeline. Often, it is the

culmination of irregular immigration status—an expired visa, a failed asylum

claim, or, in many Gulf countries, an unresolved dispute with an employer.

In high-profile cases, deportations may be politically motivated or linked

to severe legal violations.

Kenyan diplomatic missions abroad offer consular support, but their capacity is often strained, especially in regions with high numbers of distressed migrant workers, such as the Middle East.

The Kenyan

Embassy in Doha, for instance, outlines its role as ensuring “a fair and speedy

trial” and humane treatment for detainees, but explicitly states, “the Embassy

does not provide any financial assistance or bond facilities for detained

Kenyans.” This lack of a safety net leaves many migrants painfully vulnerable.

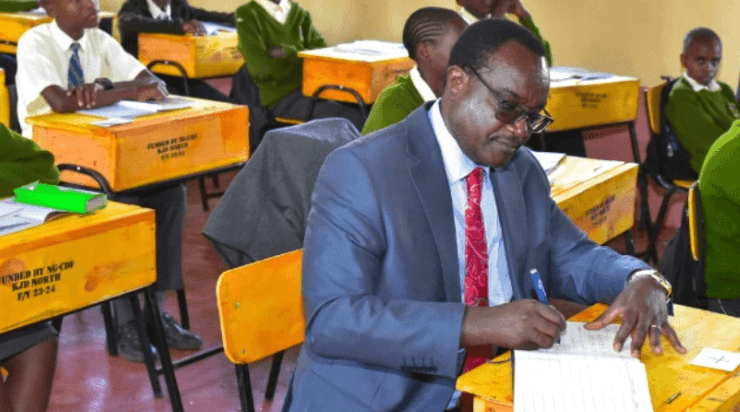

The deportation process itself is often swift

and opaque. Kenyan immigration and security officials follow a structured

protocol when a Kenyan national is deported, according to government sources.

The procedure involves coordination between foreign authorities, the

Directorate of Immigration Services, and local security agencies to ensure

proper identification, security screening, and legal processing of returnees.

Deportation typically begins with formal

communication from the foreign government. Kenyan embassies abroad are notified

before the individual boards the return flight. Where the deportee lacks valid

travel documents, the Kenyan mission issues temporary permits to facilitate

travel.

Upon arrival—usually at Jomo Kenyatta

International Airport (JKIA)—the deportee is received by immigration officers

and, depending on the case, detectives from the Directorate of Criminal

Investigations (DCI) or the Anti-Terror Police Unit (ATPU).

Foreign escorting officers hand over documentation detailing the reasons for

deportation, including immigration violations or criminal allegations.

Authorities then conduct identity

verification, followed by an initial interview and security screening to assess

the circumstances leading to the removal. The next steps depend on the gravity

of the allegations.

Individuals deported for minor infractions such as overstaying visas are

typically released after routine processing. Those linked to criminal activity,

fraud, or security-related concerns undergo further interrogation and may be

detained if they are wanted in Kenya or if local investigations are pending.

Where no Kenyan charges exist, the individual

is cleared after screening, although authorities may monitor those flagged for

potential risks. Immigration records are updated to reflect the deportation,

and travel documents are examined for authenticity.

Once released, deportees are treated as

ordinary citizens unless local charges arise. Reintegration is handled privately

by families, with limited state involvement beyond security and immigration

compliance. Officials emphasise that deportation is an administrative process

rather than a punitive one—unless Kenyan law has been violated.

Despite existing diaspora services—such as the

Diaspora Investment Support Office (DISO)—direct, comprehensive reintegration

programmes for deported citizens remain critically insufficient.

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) advocates for “humane and

orderly migration,” but for involuntary returnees, the process is far from

orderly. Kenya lacks a structured national strategy to address the unique needs

of deportees, who require psychosocial support, job placement guidance, and

financial literacy training.

In the absence of robust reintegration

mechanisms, many fall through the cracks, relying on fragmented community and

family support systems that are often quickly exhausted.

The journey of a deported Kenyan is a

cautionary tale—a dark facet of global migration. It is a story of dashed

aspirations, legal vulnerability, and a crushing return to a country unprepared

for their landing. It underscores the urgent need for stronger foreign policy

to protect citizens abroad and domestic policy to support those whose dreams

have been violently revoked.

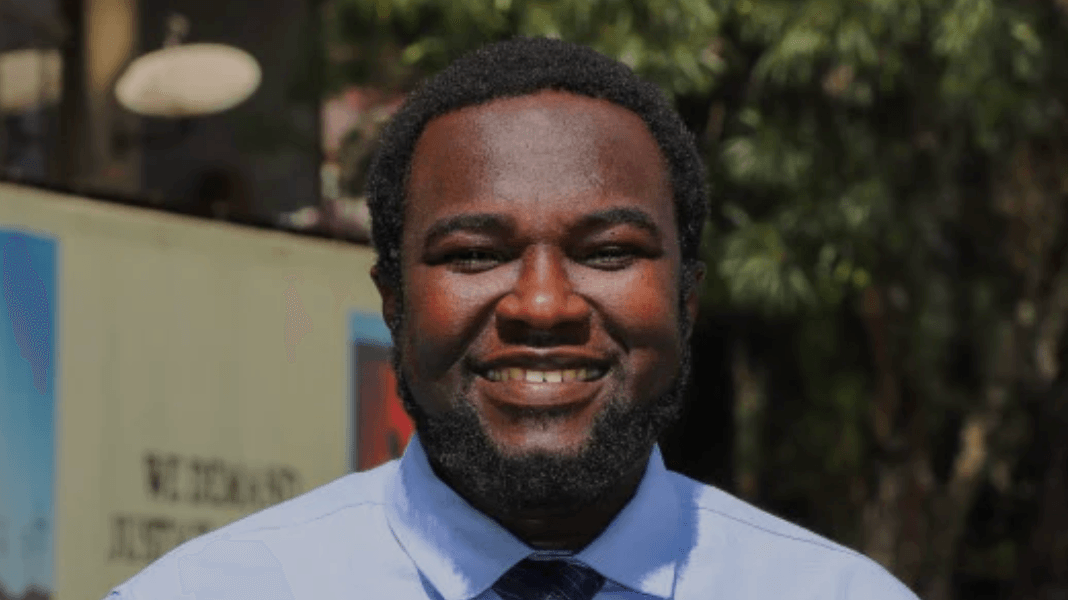

“My goal is to go back to Kenya and figure it out,” Samwel Kangethe, a

Kenyan man who chose to self-deport from the U.S. after years of legal limbo

following a disputed residency renewal, told a U.S.-based outlet.

“The family has lost that income. They only have one income now. Sam is

going back to Kenya, and it's going to be really complicated for the family to

live in Michigan.”

Beyond

financial hardship, deported individuals face psychological distress, social

stigma, and the trauma of a forced return. Many come home with nothing but the

clothes on their backs—and the heavy burden of dreams abruptly undone.