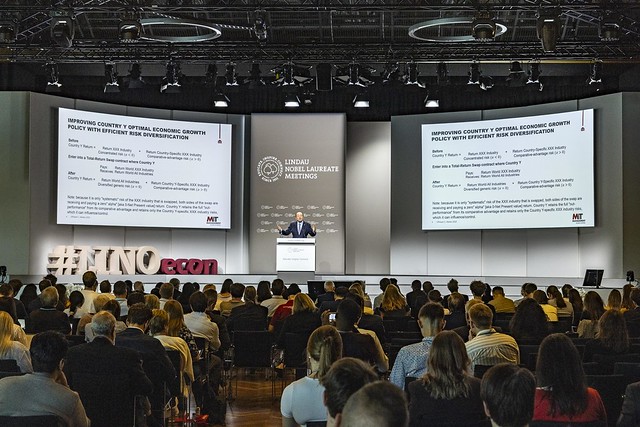

Young scientists follow proceedings during Nobel Prize-winning economist Simon H. Johnson’s presentation at the 8th Lindau Nobel Meeting on Economic Sciences in Lindau, Germany, on August 28, 2025

Young scientists follow proceedings during Nobel Prize-winning economist Simon H. Johnson’s presentation at the 8th Lindau Nobel Meeting on Economic Sciences in Lindau, Germany, on August 28, 2025

As artificial intelligence (AI) continues to move rapidly into workplaces and economies across the world, a pressing question remains: will the technology bring inclusive growth, or will it deepen inequality by pushing workers out of jobs?

Economists warn that AI is set to

disrupt labour markets on a scale not witnessed since the Industrial

Revolution, with consequences that will reverberate far beyond the economy.

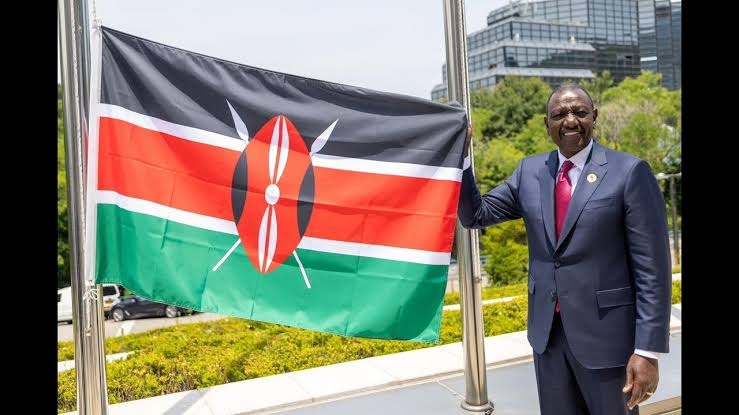

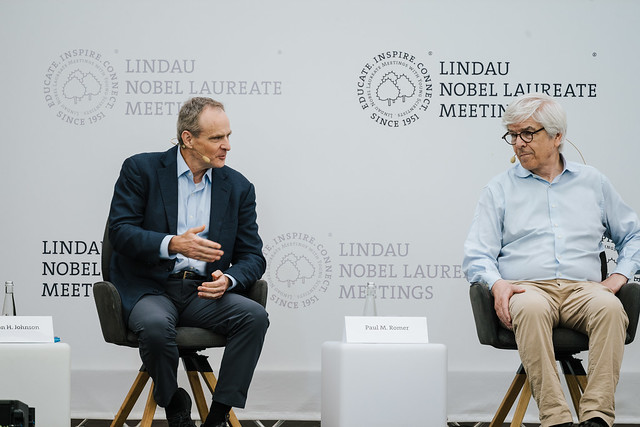

At the 8th Lindau Nobel Meeting on Economic Sciences in Germany, Nobel

Prize-winning economist Simon H. Johnson issued a cautionary note.

He argued that AI is likely to accelerate skill-biased technological change,

pushing labour markets into deeper polarisation.

White-collar jobs, he noted, are already among the most vulnerable. Johnson,

who shared the 2024 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences with Daron

Acemoglu and James Robinson, reminded his audience that technology has never

been neutral.

In his words, technology is always a choice, shaped by decisions on how it

is developed, who gets access to it, and what kinds of jobs emerge from it.

The stakes, according to new reports, are immense. The World Economic

Forum’s Future of Jobs Report 2025 shows that 40 percent of employers

expect to cut clerical and administrative roles as a direct result of

automation.

The International Labour Organisation’s Generative AI and Jobs Report

2025 echoes these concerns, pointing out that one in four jobs globally is

directly exposed to AI.

The risks are highest in advanced

economies and particularly for women, who make up the majority of clerical

workers.

Still, AI is not only about job losses. The World Economic Forum projects a

net gain of 78 million jobs by 2030 as new industries take root and new types

of work emerge.

Similarly, PwC’s Global AI Jobs Barometer 2025 highlights that workers with AI skills are already earning a 56 percent wage premium, and sectors that adopt AI show productivity growth three times higher than those in traditional industries.

Johnson, however, warned that such benefits will not be evenly shared.

He pointed out that sixty per cent of the United States labour force does

not hold a college degree, leaving them especially vulnerable in this wave of

technological change.

The better-off, he observed, are positioned to thrive, while those with less

education will experience mounting pressure.

To him, the danger is not just economic but political. Rising inequality, he

argued, carries the risk of destabilising societies.

If AI deepens the patterns already visible from the last forty years of

digital transformation, then further polarisation and public anger will be

difficult to avoid.

The larger question, he said, is whether democracies will have the strength

to respond to these challenges or whether widening inequality will weaken them

further.

His warnings carried echoes of the last digital revolution, which rewarded

high-skilled workers but left many others behind.

Without checks, he cautioned, AI could easily become a new driver of social

unrest.

For Johnson, the central issue is not whether AI will advance productivity

and science, it certainly will, but whether those gains will reach the people

who need them most.

He called on governments and industries to act deliberately in shaping the

future of AI.

In his view, AI policies must be designed to generate work opportunities for

people without college degrees. Investment in large-scale reskilling programmes

is essential if vulnerable workers are to stand a chance in the new job market.

Social safety nets must be strengthened to support those displaced by

automation, and fairness must extend beyond advanced economies to ensure that

AI also creates opportunities in the Global South.

Without such steps, Johnson warned, the deployment of AI by the tech

industry will only reinforce polarising trends, deepening inequality both

within and across nations.

In the end, his message was clear. Artificial intelligence is not destiny.

It is a choice, and societies must decide whether it becomes an engine of

shared prosperity or an accelerant of exclusion.