A community clinic comes to life

Subukia Primary School had traded chalkboards for stethoscopes that Saturday.

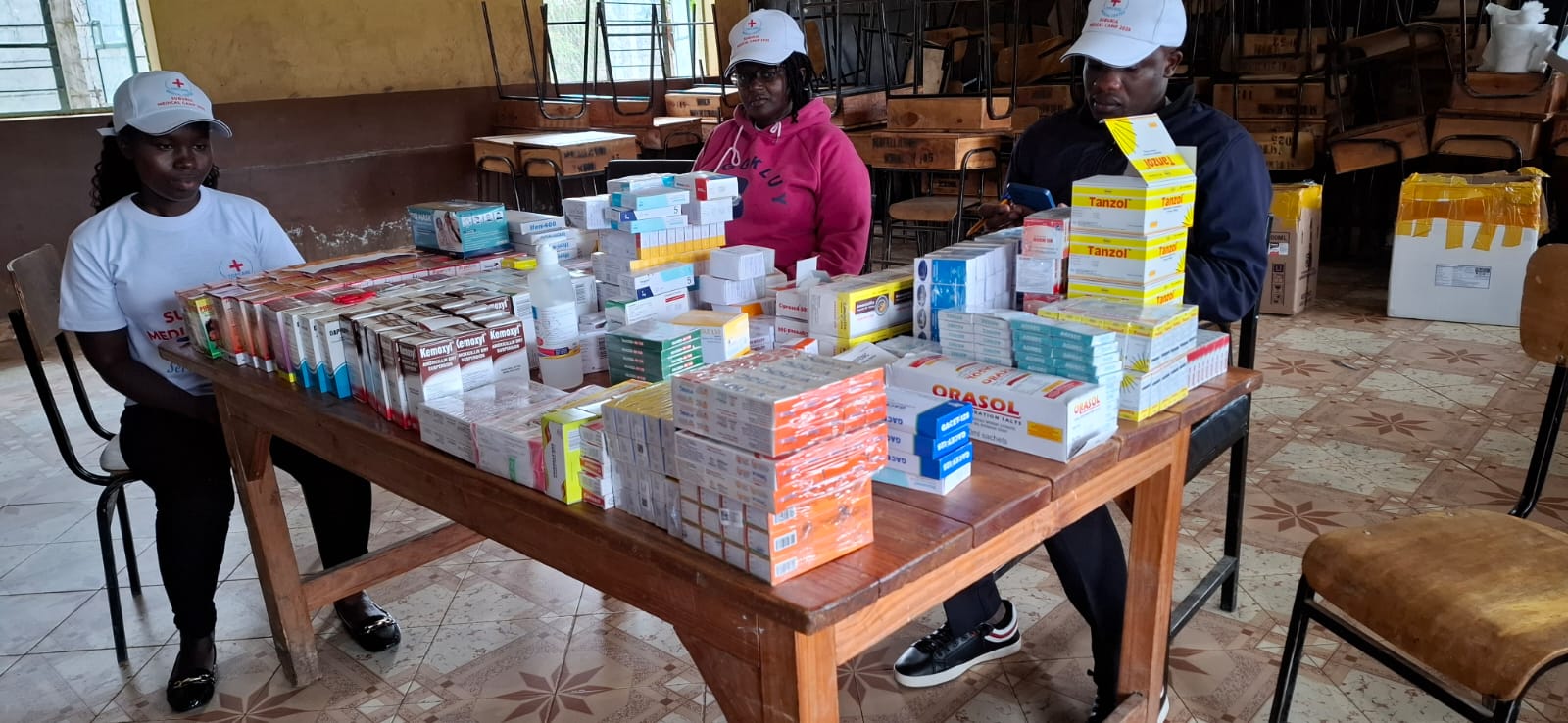

In Nakuru County, a mild morning buzzed with unusual energy. Classrooms morphed into mini clinics, one room stocked like a pharmacy, another flaunting an eye chart on the wall.

Nurses shuffled strips of paper across desks, and clinicians unpacked portable equipment.

Outside, the schoolyard swelled with Subukia residents ready to claim the medical attention they had long postponed. The hum of learning had been replaced by the pulse of care.

The free medical camp was organised by Top Care Nursing Home and staged at the school on Saturday, August 16, 2025.

But it was more than just blood-pressure readings. Residents received general medical consultations, eye checks, blood sugar tests, gynaecological screenings, joint assessments, and free screenings for hypertension, diabetes and other silent diseases.

Health education talks were held under the shade of tents, while SHA insurance registration assistance was also provided.

After consultations, patients who needed medicine walked away with it free of charge- dispensed from a makeshift classroom pharmacy.

For many, the clinic was not just an event. It was a rare doorway back into care.

A quiet warning

“Prevention is better than cure,” said Samuel Otieno, the overall hospital administrator at Top Care Medical Centre.

Moving briskly between tents and classroom-turned-consulting rooms, he spoke with volunteers, counselled patients and offered reminders.

Otieno, a trained medical laboratory officer, kept repeating one message: silent diseases are common, and the cost of ignoring them is devastating.

“If you detect a disease early, you can prevent complications,” he said. “You can advise on diet. You can avoid expensive treatment later. You can save a life.”

Leaning on the doorframe of a classroom fitted with a table, chair and cervical screening chart, he added: “You can go to a hospital and just get checked. You can ask about your blood sugar. You can check your blood pressure and just know how it is.”

The rooms where it happened

Inside a classroom, an elderly woman’s eyesight was tested against a Snellen chart. In another, a clinician explained Pap smear results in the local language.

Across the hall, cardboard boxes doubled as pharmacy shelves, holding strips of tablets beneath a handwritten sign that read simply: MEDICINE.

“Putting services in the school changes the whole mood,” said Dr Jane Rotich, a therapist from Nakuru Provincial General Hospital who had travelled to Subukia to examine joints and advise on physical therapy.

“People are less intimidated. They ask questions. They listen. They can see that checks are simple,” Dr Rotich added.

At the eye station, a patient blinked behind her reading glasses. “I have not been to the hospital in years,” she said quietly. “I am happy they checked my eyes.”

The anatomy of a delayed diagnosis

The camp’s main focus was on non-communicable diseases- hypertension, diabetes, prostate and cervical cancers, and joint disorders.

They often progress silently, building damage in the background until a stroke, fracture, or advanced tumour forces an emergency.

“In this community, and many parts of Kenya, people come late,” Otieno said. “Women come more often than men. Men wait until they cannot walk, or until they collapse. That’s when they come to hospital.”

The camp aimed to break that pattern. “If a woman comes for cervical screening and we detect an abnormality early, we can manage it," Otieno expressed.

“We don’t wait until it is stage four. A simple blood test can point to prostate problems in men. You don’t have to wait to be in pain," Otieno emphasised.

The human cost

Not all problems can be solved with a single tablet. Ernest Nyang'au, 73, carried the weight of failed treatments and persistent pain. After a fall, an implant in his leg had shifted.

Despite a month in Nakuru Provincial General Hospital, the problem remained unresolved. He lives with a chronic wound and painful varicose veins that make walking a daily struggle.

“Health is paramount,” Ernest said, pointing to his leg. “If you are healthy, you are a rich man. If you are sick, you are a poor man.”

At the camp, he received dressings and a referral for further treatment in Kitengela. “I hope they do the procedure,” he said. “I will be a rich man if they do.”

Ernest’s story is neither rare nor sensational — it is the arithmetic of unmet need. For him, the camp was a bridge to yet another appointment, and perhaps a chance at relief.

Who shows up and why

Women crowded most of the gynaecology station chairs, while men were noticeably fewer. Nurses and doctors pointed to social norms. “Women are used to going for services, especially around reproductive health,” Otieno explained.

“Men are taught to be strong and not to complain. They think checking means there is something wrong. That’s how the myths grow," Otieno added.

But the consequences are grave. A man who postpones a prostate exam is more likely to discover cancer at an advanced stage.

A person who ignores raised blood sugar may later require insulin and lengthy hospital stays- complications that a change in diet might have prevented.

Still, in Subukia, the turnout showed hope. “People come because it is free and because it is close,” said Charles Wangombe, one of the patients. “Older people here need special care. This brings care close to us.”

From check-up to follow-up

The true test of any outreach camp lies in what follows after the tents come down. A sugar reading scribbled on a slip of paper means little without follow-up.

The classroom pharmacy helped with immediate needs, but organisers also emphasised referrals and education.

“If we find high blood sugar, we advise on diet and lifestyle first,” Otieno said. “If it remains high, we refer. This is not a one-day wonder. It must link into the health system.”

Dr Rotich agreed. “We are trying to prevent chronicity. If we can keep a person working and independent, we reduce the cost to families. Early intervention saves money and dignity.”

Small gestures, big outcomes

From ointment for skin infections to tablets for blood pressure, the pharmacy dispensed small packets of medicine and larger doses of hope.

Hanna Wairimu left clutching her medication. “I didn’t pay for it,” she said. “They told me to come back for regular checks.”

It was a guarded relief- gratitude mixed with the knowledge that health requires more than a single visit.

A responsibility of continuity

For Otieno and Dr Rotich, the camp was a necessary starting point, but not a cure-all. “Camps can open doors,” Otieno said. “But they must lead to sustained care."

That remains the challenge in a health system stretched by distance, cost and staff shortages.

For patients like Ernest, continuity is the difference between hope and disappointment. For others, it is the difference between early management and irreversible disability.

A community lesson

As the afternoon sun tilted across the schoolyard, the lines shortened. Nurses tallied results, volunteers packed up kits, and patients walked away with medicine, referral slips, and the promise of follow-up.

Some whispered quiet pledges: “I will go back. I will tell my neighbour. I will not wait until it is too late.”

At the gate, Otieno watched them leave. “We want people to make checking a habit,” he said. “To come even when they feel fine. That habit prevents complications. That habit keeps families whole."

The Subukia camp did not erase poverty. It did not repair every broken promise in Kenya’s health system.

However, it did something powerful- it turned classrooms into places of healing and reminded a community that health is not only an emergency service.

The message was simple, human and urgent: Check early. Act early. And never let pride or fear keep you from seeking care.