Each day for the last ten years on death row stretched into eternity for Stephen Munyakho. The nights were even longer.

But nothing compared to what inmates called “dark days”—when one among them was summoned for execution.

“Mum, today we saw darkness,” Munyakho would whisper into the phone during their weekly ten-minute calls—his only window to the outside world.

In his first year behind bars, he saw more than 100 fellow prisoners led out to what they called the slashing field—a crude euphemism for the place of execution.

“You eat with someone, even joke with him and the following day he is taken away for execution,” he recalled. “It was very moving and frightening.”

Housed in a death row facility meant for 150 inmates but holding 480, Munyakho witnessed half of them meet their end.

Somehow, fate kept pushing his day forward as his family back home in Kenya fought to raise blood money, hoping to spare his life under Shariah law.

“It is a pure miracle that I’m here today,” he said. “It is miraculous that I was not taken to the gallows.”

Even in the darkest moments, Munyakho said a silent voice often whispered within him that somehow, some way, he would survive.

“I would sit in that small cell, listening to the silence and there was always this voice that said, ‘You will leave this place alive.’ It never left me.”

Munyakho describes Saudi prisons as largely free of physical abuse but emotionally punishing—with no violence, but the isolation was unrelenting.

At first, remand inmates were given newspapers— to break the monotony. But eventually, even printed material was withdrawn.

“We were like chicken—fed well, given different food varieties, but denied everything else,” he said.

“You just wake up, eat, sit the whole day, pray and go back to your room to sleep.”

Once a week, they were allowed a phone call home.

“They would give us 10 minutes for a call. Who do you talk to and who do you leave out?” he asked. “And once the time lapsed, the call would freeze immediately. It was a booth. There was no extension.”

When a week passed without a call, his family feared the worst—that he had finally been selected for execution.

Munyakho’s ordeal began in April 2011. Then a warehouse manager in Saudi Arabia, he got into an altercation with a Yemeni colleague, Abdul Halim Saleh. Saleh was stabbed in the chest but managed to walk to a hospital, where he later died.

Munyakho also suffered stab wounds and was taken to hospital, instead of straight to jail, by police officers who found him bleeding at the scene.

Initially convicted of manslaughter in February 2012, his case took a turn in June 2014, when a Shariah court reclassified it as murder—placing him directly in line for execution. That sentence would hover for ten long years.

Under Saudi law, executions for murder require the consent of the victim’s heirs. But one of Saleh’s sons was still a minor in 2014 and only reached legal age in 2024.

His mother, Dorothy Kweyu, spent years raising the diya (blood money). A proposed settlement of 10 million Saudi riyals (Sh352 million) was eventually negotiated down to 3.5 million riyals (Sh129 million) in late 2024.

It was still insurmountable—until a diplomatic appeal by President William Ruto led the Muslim World League to cover the bulk of the amount. Even so, Kweyu’s grassroots fundraising efforts were crucial.

“The ambassador’s first question was to ask how much we had to demonstrate our seriousness. You know empty hands do not help,” she recalled. In total, her campaign raised Sh20 million—just enough to earn goodwill and buy her son time.

“It is joy unspeakable,” she said after Munyakho's release was confirmed.

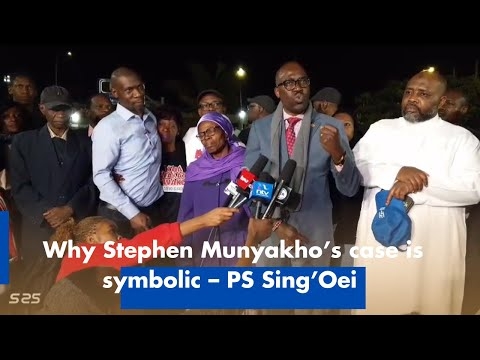

“We have had high moments, but also very low moments pursuing the life of my son.” Munyakho’s scheduled execution in May 2024 was stayed amid diplomatic negotiations. And on July 22, the Saudi courts formally cleared him for release.

He returned to Kenya on Tuesday to begin a new life—his freedom nothing short of a miracle. The only thing of value he says he brought back was his conversion to Islam. Economically, the promise of better wages had not outweighed the cost of losing a decade behind bars.

“I think I

was divinely destined to be in that country and to be in jail that long,” he

said. “I can only say it was God who ordained this path for me while I was

still in my mother’s womb.”