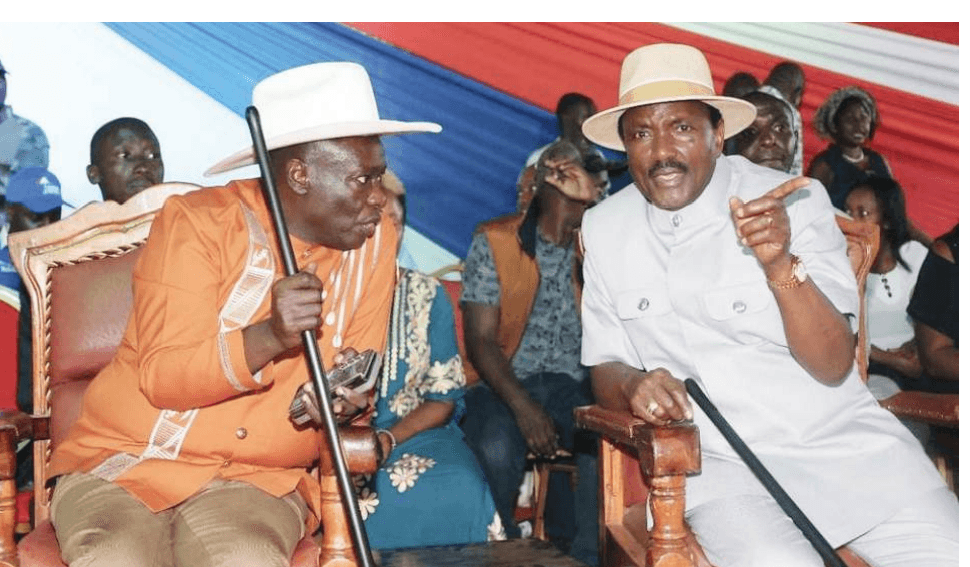

Gumato Roba and Arbe Abudo tend to chicken in Turbi ward, North Horr, Marsabit county /GILBERT KOECH

As the impact of climate change becomes severe, women in Marsabit are now embracing poultry farming as a source of livelihood.

Poultry keeping, women here say, helps give them a sense of ownership. Being a patriarchal society, just like many other pastoralist communities such as the Maasai, among others, livestock such as goats, sheep, cows or even camels belong to men.

“We are used to keeping livestock such as goats, camels and cows. The livestock belong to men,” Arbe Abudo, 52 said.

Abudo is the chairperson for the Shurr community conservancy in Turbi ward, North Horr, Marsabit county.

Within the community, there seems to be a change of mindset, as they previously did not keep chicken as a source of livelihood.

“Every time the drought comes, it wipes out everything, and we only depend on food relief. But with chicken, we can get eggs and meat,” Abudo, a mother of six said.

She said the women's group now has a sense of ownership through farming poultry. They were trained not only on how to keep poultry but also to do kitchen gardening which has improved nutrition in the community.

They plant sukuma wiki and spinach in their gardens. The women were provided with 100 chicks by conservation NGOs to start their project.

Under the project, 20 conical garden structures were built, and three poultry houses were established with 300 birds for various women and youth groups.

Households have since built their own gardens and sold surplus vegetables, a move that has strengthened food security and income.

The initiative, supported under the Voices for Just Climate Action programme, focuses on empowering indigenous communities in Shurr, Marsabit county, to secure their rights to natural resources, improve their livelihoods and protect their natural heritage.

It addresses the impacts of climate change in a dryland context by building the community’s resilience through practical, locally driven solutions that blend traditional knowledge and climate-smart innovation.

The main objective is to catalyse and amplify community voices in climate discourse and practice, using local resources and governance to promote adaptation and sustainable land use.

Abudo said the group she leads needs more chicken as well as kitchen gardens, as they have proven to be successful. She said more water supply will further improve their livelihoods and health outcomes.

Biodiversity, research and innovation manager at the World Wide Fund for Nature-Kenya, Dr Yussuf Wato, says his organisation is building household livelihoods to improve the well-being of the communities.

“The community here is very patriarchal. All the livestock is owned by men, but now with the poultry, it is all 100 per cent owned by women,” Wato said.

Wato, who comes from the area, says within the area, chicken are not held with as high regard as other livestock, as they call them “flying animals”.

He said women have adopted poultry keeping and men do not compete with women for it. To further improve the rangeland, Wato said they are working with the Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organisation to look at drought-resistant livestock with high yields.

“One of the adaptive measures, especially for pastoralist communities, is to move them from poor-quality livestock to improved livestock. However, when you look at the ecosystem here and the weather patterns, the area is very dry. We are working with Kalro to try and look at whether we can get an improved breed specifically adapted to this area.”

Wato added, “This process is going on, and we hope that maybe in the future, we shall also go towards improving breeds as an alternative way of reducing the numbers but getting improved quality livestock.”

Kalro director in charge of the Beef Research Institute, Dr Tura Isako said a number of initiatives aimed at delivering improved breeds are ongoing.

“We are doing community-based breeding programmes. We breed nucleus at national centres like beef in Kalro Lanet and dairy in Naivasha. We breed the high-quality breeds that are climate smart, and then we partner with counties and train breeder groups where they can assist in keeping improved breeds for the community, and they can supply the community,” Isako, who also comes from the community, says.

WWF-Kenya Africa's Food Future initiative lead Nancy Rapando said the initiatives that have been undertaken at Marsabit show that with enough resources, communities can build their resilience.

“The kitchen gardens are aimed at ensuring communities diversify their diets, and also start integrating vegetables. This community being a pastoral community never used to use vegetables; they would use wild fruits. And if they must use vegetables during the climate crisis, then they are buying cabbages all the way from Marsabit, which is very far,” Rapando says.

She said poultry farming has helped change the mindset. “What women have told us is that having chicken is the only asset that they own, and they are able to decide when to use it as food, and they also say that they are now eating a lot of eggs. So that means we are resolving one thing in terms of asset ownership by women but also ensuring the eggs also provide enough food for them.”

Rapando said the women would only eat chicken when they went for conferences, as it was considered a taboo.

Women have also been provided with energy-saving jikos under the project. Some 60 jikos have since been provided. Gumato Roba, 26, has since ditched a three-stone jiko she has used for decades.

Roba, a mother of three children, said the energy-saving jiko does not emit a lot of smoke and uses less firewood. She said they used to go to the bush three times a week for firewood, but that has since reduced to once in a week.

Rapando said the move has helped reduce the destruction of the remaining trees in the area.

“The project is quite holistic because it resolves a number of challenges in terms of incomes, in terms of diversifying diets and also in resolving the climate crisis.”

Gumato Roba in her Manyata.